HISTORY108 - Natural Wonders of Northern Arizona

Northern Arizona has always been a favorite place for Pat and me to visit. There is so much spectacular scenery. Natural wonders abound - with such a variety of colorful canyons, mountains, deserts, and majestic monuments - that share an early geologic history, but that later underwent different natural processes to make each of these natural wonders truly unique.

This blog will discuss the

history of several of these natural wonders, with emphasis on what makes them

so different from one another. I have

arbitrarily defined Northern Arizona as that part of Arizona that lies north of

Interstate 40. After an introduction to

the region and its early geology, I will talk about the Grand Canyon; the San

Francisco Volcanic Field, highlighting Sunset Volcano Crater; the San Francisco

Peaks; Antelope Canyon; Monument Valley; the Painted Desert, highlighting the

Petrified Forest; Canyon De Chelly; Window Rock; and finally, the fascinating

special case of Meteor Crater.

This blog will cover natural wonders in northern Arizona identified by the red circles.

I will list my primary sources at

the end.

Introduction

The

geologic story of northern Arizona began almost two billion years ago when the

liquid magma surface of the Earth began to cool and formed igneous rocks. Over hundreds of millions of years,

metamorphic rocks formed under intense heat and pressure, and above these old

rocks, layered deposits of sediments from successive Earth environmental

periods hardened into sedimentary rocks.

Then, between 70 and 30 million years ago, through the action

of plate tectonics (movements of pieces of the Earth’s crust), the whole region

was uplifted, resulting in the Colorado Plateau, a semi-arid, mostly flat-lying region,

ranging from 5,000 to 8,000 feet in elevation, centered on the Four Corners

region of the southwestern U.S.

Northern Arizona is virtually entirely located on the Colorado Plateau.

This plateau

covers an area of 130,000 square miles within western Colorado, northwestern New Mexico, southern and

eastern Utah, northern Arizona, and a tiny

fraction in the extreme southeast of Nevada. About 90% of

the area is drained by the Colorado River and its

main tributaries: the Green, San Juan, and Little Colorado. Most of the remainder of the Plateau is

drained by the Rio Grande and its

tributaries.

The

Colorado Plateau is largely made up of high desert, with scattered areas of

forests, and is known for its rugged landscape and variety of

environment. This relatively high, semi-arid region has produced many

distinctive erosional features such as arches, domes, arroyos, deep canyons, cliffs, fins, natural bridges, pinnacles, hoodoos, monoliths, and slot canyons.

The Ancestral

Puebloan People lived in the region from roughly 2000 to 700 years ago. The first sighting of northern Arizona by a European is

credited to the Francisco Coronado expedition of 1540 and subsequent

discovery by two Spanish priests, Francisco Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez

de Escalante, in 1776. In the early

1800s trappers examined it, and sundry expeditions sent by the U.S. government

to explore and map the West began to record information about the region. The first known descent of the Colorado River

by boat was in 1869, during an expedition led by geologist and

ethnographer John Wesley Powell.

During the 1870s Powell and others conducted subsequent expeditions to

the region, and extensive reports on the geography, geology, botany, and

ethnology of the area were published.

Construction of

the Hoover Dam in the 1930s and the Glen Canyon Dam in the

1960s changed the character of the Colorado River. Dramatically reduced sediment load changed its

color from reddish brown (Colorado is Spanish for

"red-colored") to mostly clear. The apparent green color is

from algae on the riverbed's rocks, not from any significant amount

of suspended material.

Grand Canyon

The Grand Canyon lies in the

southwestern portion of the Colorado Plateau, and consists essentially of

horizontal layered rocks and lava flows.

The broad, intricately sculptured chasm

of the canyon contains between its outer walls a multitude of imposing peaks,

buttes, gorges, and ravines. It ranges

in width from about 175 yards to 18 miles and extends in a winding course from

the mouth of the Paria River, near Lees Ferry and the northern boundary of

Arizona with Utah, to Grand Wash Cliffs, near the Nevada state

line, about 277 miles. The Grand Canyon

also includes many tributary side canyons and surrounding plateaus.

Well after the uplifting formation of the Colorado Plateau

tens of millions of years ago, only about 5-6 million years ago, the Colorado

River began to carve its way downward through the horizontal layers of rock and

sediments, exposing hundreds of millions of years of the Earth’s environmental

history. Each layer has a story to tell.

The downcutting of the Colorado River has exposed hundreds of millions of years of northern Arizona’s environmental history.

Continued erosion by rockslides and tributary

streams has led to the widening of the canyon and the formation of temples and

buttes that we see today. These forces of nature are still at work slowly

deepening and widening the Grand Canyon.

Today, the Colorado River, at the

bottom of the Grand Canyon, lies more than 6,000 feet below its rim. The North Rim, at approximately 8,200 feet above sea

level, is some 1,200 feet higher than the South Rim. In its general color, the

Grand Canyon is red, but each stratum or group of strata has a distinctive hue

- buff and gray, delicate green and pink, or, in its depths, brown, slate-gray,

and violet.

The Colorado River, over millions of years, has forged this spectacular Grand Canyon.

The spectacular Grand Canyon, offering

incomparable vistas, was designated as a national monument in 1908 and a

national park in 1919. In 2023,

4,733,705 people visited Grand Canyon National Park.

San Francisco Volcanic Field / Sunset

Volcano Crater

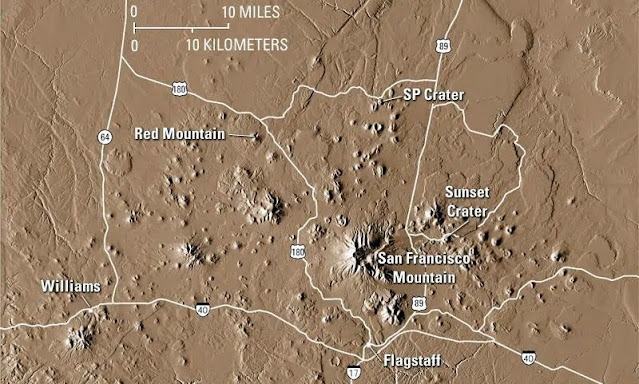

The San Francisco Volcanic Field

(SFVF) is an area of volcanoes in northern Arizona, north

of Flagstaff. The field

covers 1,800 square miles of the southern boundary of the Colorado

Plateau. This is an area of intense

volcanic activity that began about 6 million years ago, near present-day

Williams, about the time that the Colorado River began carving out the Grand

Canyon.

The SFVF is dotted

with more than 600 volcanoes (see figure below), ranging in size from

relatively small cinder cones, through medium-size lava domes, up to the

stratovolcano, San Francisco Mountain (see next section).

Generally, eruptive activity within

the field has shifted slowly from west to east over the last 6 million

years. The SFVF is still geologically

active; it is only temporarily dormant.

The most recent eruption in the SFVF,

some 939 years ago in the year 1185, produced the Sunset Crater cinder cone,

about 20 miles northeast of Flagstaff.

During the eruption, the ground split open along a fissure nearly 6

miles long, and lava erupted out of it to great heights, forming the

1,120-foot-high Sunset Crater cinder cone.

The eruption produced a blanket of ash and pebble-sized fragments of

volcanic material covering an area of more than 810 square miles. As the surface of the lava cooled, hot lava

continued to flow underneath and occasionally broke through the cooler surface,

creating the jagged landscape seen on the lava flows today. These slow-moving flows filled in two small

valleys to a depth of 100 feet or more.

The Sunset Crater Volcano eruption in 1185 produced an 1,120-foot-high cinder cone.

Sunset Crater Volcano National

Monument was established by President Herbert Hoover in 1930 to preserve its

geologic formations. Today the monument

occupies 3,040 acres and is surrounded by Coconino National Forest. Since 2000, Sunset Crater Volcano National

Monument has had an average of around 165,000 visitors each year.

San Francisco Peaks

The San Francisco Peaks are a volcanic mountain range in the San Francisco Volcanic Field in north

central Arizona, just north of Flagstaff. The highest summit in the

range, Humphreys Peak, is the highest point in the state of Arizona at 12,633

feet in elevation.

The San Francisco Peaks are the eroded

remains of a single, once-much-higher, stratovolcano called San Francisco

Mountain (SFM). (Stratovolcanoes are large conical volcanoes composed of many

alternating layers of hardened lava, and looser cinders, plus pumice and ash,

deposited during multiple eruptions, typically over many thousands of

years.) The SFM volcanic cone was

constructed by multiple eruptions between 900,000 and 400,000 years ago.

Sometime between the end of the last

major eruptions 400,000 years ago and about 100,000 years ago, the top and

northeast flank of SFM collapsed in a gigantic avalanche that spilled outward

toward the northeast.

View of San Francisco Mountain from the east, outlining its original shape and maximum elevation, and showing the seven mountain peaks that remained after its collapse.

A great deal of erosion, caused by the

growth and expansion of mountain glaciers, has taken place since the east side

of SFM collapsed, and produced the peaks that we know today.

Today view of the San Francisco Peaks from the east.

Groundwater from a sinkhole in the San Francisco Peaks

supplies much of Flagstaff's water while the mountain range itself is in

the Coconino National Forest, a popular recreation site. The Arizona Snowbowl ski area is on

the western slopes of Humphreys Peak, and began ski operations in 1938.

Antelope Canyon

Antelope Canyon is a slot

canyon on Navajo Nation land about 5 miles southeast of the town of Page. (A slot canyon is a long, narrow channel or

drainageway with sheer rock walls that are typically eroded into

either sandstone or other sedimentary rock.) Antelope Canyon includes six separate, scenic

slot canyon sections on the Navajo Reservation, referred to as Upper Antelope

Canyon, Rattle Snake Canyon, Owl Canyon, Mountain Sheep Canyon, Canyon X, and

Lower Antelope Canyon. It is the primary attraction of Lake Powell

Navajo Tribal Park.

Antelope Canyon was formed, over the course of millions of years, since the uplifting of the

Colorado Plateau, by the erosion of Navajo Sandstone due

to flash flooding and wind.

Navajo Sandstone was

formed from the compacted sands of ancient deserts. Over millennia, these dunes

solidified into the rock, setting the stage for the canyon’s formation. The uniformity and softness of Navajo

Sandstone made it particularly susceptible to the forces of erosion, which played a pivotal role in sculpting Antelope

Canyon.

Despite its arid climate, this region

is prone to sudden and violent flash floods, especially during

the monsoon season. When rain

falls over the canyon, it rushes into the narrow passageways, carrying with it

sand and debris. This natural

sandblasting process eroded the sandstone walls, gradually carving out the

canyon’s sinuous shapes and smooth, flowing contours.

Wind erosion contributed to the

canyon’s formation by whisking away loose sand and sediment. This action helped smooth and polish the

canyon walls, giving them their characteristic sheen. The intricate patterns etched into the rock

surfaces resulted from the relentless yet delicate touch of the wind.

Visitors to Antelope Canyon typically

climb down ladders into the canyon, and from underground, can observe direct

sunlight radiating down from openings at the top of the canyon, which make the

inside canyon very colorful.

The incredible beauty of Antelope Canyon.

Antelope Canyon is a popular location

for sightseers, and a source of tourism business for the Navajo

Nation. The slot canyons are accessible

only by Navajo guided tours, offered since 1983.

Monument Valley

Monument Valley is a region of

the Colorado Plateau characterized by a cluster of sandstone buttes,

with the largest reaching 1,000 feet above the valley floor. The most famous butte formations are located

in northeastern Arizona along the Utah-Arizona state line. The valley is considered sacred by

the Navajo Nation, within whose reservation it lies.

The elevation of the valley floor

ranges from 5,000 to 6,000 feet above sea level. The floor is largely siltstone or

sand derived from it, deposited by the meandering rivers that carved the

valley. The valley's vivid red

coloration comes from iron oxide exposed in the weathered siltstone. The darker, blue-gray rocks in the valley get

their color from manganese oxide.

The formation of Monument Valley began

about seventy million years ago. During

this time the entire Monument Valley area was covered by a shallow sea. When the Colorado Plateau bulged upward and

broke apart, the sea water drained away. The incredible formations of Monument Valley were created

over millions of years through a combination of wind, water, and ice erosion.

These natural forces wore away the softer rock layers, leaving behind the more

resistant sandstone formations. The

result is a landscape dotted with isolated monoliths, spires, and mesas, each

with its own unique shape and character.

The majestic formations of Monument Valley.

The towering buttes and mesas are

composed primarily of four layers of rock. The topmost layer is a reddish-brown

siltstone and sandstone that dates to around 240 million years ago. Beneath this lies dark colored sandstone and

siltstone. Next is a layer of vibrant,

multi-colored shales, clays, and mudstones. The deepest layer visible is a

hard, durable rock that forms the towering cliffs and spires characteristic of

Monument Valley. The appearance of this layer is dark red, and uneven as it

reaches the valley floor.

Monument Valley has been featured

in many forms of media since the 1930s. Famed director John Ford used the

location for several of his Westerns. Film critic Keith Phipps wrote that

"its five square miles have defined what decades of moviegoers think of

when they imagine the American West.”

Monument Valley includes much of the

area surrounding Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park, a Navajo Nation equivalent

to a national park. Visitors may pay an access fee and drive through

the park on a 17-mile dirt road. Parts

of Monument Valley are accessible only by guided tour.

Painted Desert / Petrified Forest

The Painted Desert is

located in the Four Corners area, running about 160 miles from near

the east end of Grand Canyon National Park to the southeast. The desert is about 15 to 50 miles wide and

covers an area of about 7,500 square miles.

Elevations

range from about 4,500 to 6,500 feet.

The desert is composed of stratified

layers of sedimentary rocks, deposited 200 million years ago, which

erode easily. The

colorful hills, flat-topped mesas, and sculptured buttes of the Painted Desert are

primarily made up of these mainly river-related deposits. The fine-grained rock layers contain abundant

iron and manganese compounds, which provide the pigments for the various colors

of the region. Thin

limestone layers and volcanic flows cap the mesas.

The erosion of these layers has

resulted in the formation of the topography of the region. Wind, water and

soil erosion changed the face of the landscape by shifting sediment and

exposing layers of the deposited rocks.

An assortment of fossilized prehistoric plants and animals are

found in the region, as well as ancient dinosaur tracks and evidence

of early human habitation.

The Painted Desert is known for its

brilliant and varied colors, with formations banded with vivid red, yellow, blue, white, and

lavender. At times the air glows with a

pink mist or purple haze of desert dust. The rolling surface is broken by isolated

buttes and is bounded on the north by vermilion cliffs, rising to broad,

flat-topped mesas. Marks

of volcanic activity are abundant and widely scattered. The region is barren and arid, with 5 to 9

inches of annual precipitation and yearly temperature extremes of −25

to 105 °F.

The Painted Desert is known for its brilliant and varied colors.

The Painted Desert was named by the

Spanish expedition under Coronado in 1540. Passing through the wonderland of colors, they

named the area El Desierto Pintado ("The Painted

Desert").

Navajo and Hopi reservations occupy a large

part of the Painted Desert, and the Navajo use the variegated brightly colored

sands for their famous ceremonial sand paintings.

Part of the southeastern section of the desert is within the

northern portion of Petrified Forest National Park, where the

remains of a coniferous forest growing more than 200 million years ago

have fossilized. As the trees died, or were knocked

down by wind or water, many were carried downstream and buried by

layers of sediment. The logs soaked up groundwater

and silica from volcanic ash and over time crystallized into quartz. Giant fossilized logs, many of them

fractured into cord-wood size segments, lie scattered throughout the park. Different minerals created the rainbow of colors seen in many

pieces.

Petrified log at Petrified Forest National Park.

The Petrified Forest was first

designated as a national monument in 1906, and as a national park in 1962. Much of the Painted Desert within Petrified

Forest National Park is protected as Petrified Forest National Wilderness

Area, where motorized travel is limited.

The main road for access to the

Petrified Forest Road, starts in the north at Route 40 and ends 28 miles later

at Route 180. You can start in the north

and work your way south, or vice versa.

In 2023, Petrified Forest National

Park received 520,000 visitors.

Canyon De Chelly

Canyon de Chelly is located in

northeastern Arizona, within the boundaries of the Navajo Nation, in

the Four Corners region, just east of the town of Chinle. Canyon de Chelly is a geologic wonder with

colorful cliffs, erosion-resistant spires, and ancient ruins. The name "Canyon de Chelly" is a Spanish

corruption of the Navajo word tsegi, which means "rock canyons.”

Reflecting one of the longest continuously inhabited landscapes of North

America, it preserves ruins of the indigenous tribes that lived in the area for

up to 5,000 years.

Canyon de Chelly covers 131 square

miles and is about 1,000 feet deep. The canyon

was cut by streams with headwaters in the Chuska Mountains just to

the east of Canyon de Chelly.

Canyon de Chelly’s

bedrock is made of sedimentary rocks deposited millions of years ago. De Chelly sandstone is a prominent feature of

the canyon’s red cliffs. A grayish-brown caprock - containing sandstone

pebbles, quartz, and other materials - was deposited on top of the sandstone.

Canyon de

Chelly’s landscape is the result of millions of years of erosion by streams

and uplift. The softer layers of rock dissolved away, leaving exposed

shelves of harder rock that created the canyon walls' stair-step

appearance.

The canyon’s distinctive geologic feature,

Spider Rock, is a sandstone spire that rises 750 feet from the canyon floor.

Spider Rock rises 750 feet from the floor of Canyon de Chelly.

Canyon de Chelly is thought to have

been sporadically occupied by Hopi Indians from circa 1300

to the early 1700s, when the Navajo then moved into the canyon. Many of

the Navajo people chose to settle in Canyon de Chelly to protect themselves

from encroaching Anglo settlers as well to avoid the United States military,

who invaded the Canyon during the mid-1800s for war campaigns against the

Navajo.

Canyon de Chelly was established as a

U.S. national monument in 1931, and listed on the National Register of

Historic Places in 1970.

Canyon de Chelly is entirely owned by

the Navajo Tribal Trust of the Navajo Nation. It is the only National Park Service unit that

is owned and cooperatively managed in this manner. About 40 Navajo families live in the park

today.

Access to the canyon floor is

restricted, and visitors are allowed to travel in the canyons only when

accompanied by a park ranger or an authorized Navajo guide. Private Navajo-owned companies offer tours of

the canyon floor by horseback, hiking or four-wheel drive vehicle.

Most park visitors arrive by

automobile and view Canyon de Chelly from the rim, following both North Rim

Drive and South Rim Drive. Ancient ruins

and geologic structures are visible.

Canyon

de Chelly is one of the most visited national monuments in the United States, with 355,000 visitors in

2022.

Window Rock

The town of Window Rock is the site of

the Navajo Nation governmental campus, which contains the Navajo Nation Council, Navajo Nation Supreme Court, the

offices of the Navajo Nation President and Vice President, and many Navajo

government buildings. The geological formation of Window

Rock is a pothole-type natural arch, after which the town was named. Both are located about 50 miles as the crow

flies, southeast from Canyon de Chelly, adjacent to the Arizona-New Mexico

state line, at an elevation of about 6,800 feet.

The geological formation of Window Rock is a natural

sandstone arch about 65 feet high that was formed, over millions of

years, through a process of erosion by wind, water, and salt. Weathering,

freezing, and thawing created the smooth oval front entrance of the arch.

Window Rock arch is a geological wonder.

In ancient times people were attracted

to this place because of a spring that was located there. People would mark symbols on the rocks at the

spring. Fragments of pottery found there

established the fact that these admirers of the Window Rock lived in the area a

thousand years ago.

The city of Window Rock's population

was 2,500 at the 2020 census. It is

estimated to reach around 20,000 during weekdays when tribal offices are open. The Navajo

Nation Museum, the Navajo Nation Zoological and Botanical Park, and the

Navajo Nation Code Talkers World War II Memorial are tribal

attractions located in Window Rock.

There isn't much information about how

many tourists visit the Window Rock arch, but some

say the natural beauty of Window Rock is breathtaking and a perfect place for

contemplation.

Meteor Crater

All the natural wonders discussed so

far took millions of years to form due to the Earth’s actions of tectonic plate

movements, volcano eruptions, river cutting, and erosion from wind, water, and

salt. The final natural wonder I want to

discuss was formed almost instantaneously from decidedly “unearthly” action.

About 50,000 years ago an asteroid

smashed into northern Arizona and left a gaping hole. Meteor Crater (also called Barringer Crater)

is located about 37 miles east of Flagstaff and 18 miles west of Winslow, at an

elevation of 5,640 feet.

Meteor Crater measures 0.75 miles

across and 750 foot deep. The size of

the asteroid that produced the impact is uncertain - likely in the range of 100

to 170 feet across - but it was large enough to excavate 175 million metric

tons of rock. The crater is surrounded

by a rim that rises 148 feet above the surrounding desert. The center of the crater is filled with

690-790 feet of rubble lying above crater bedrock.

Meteor Crater was formed about 50,000 years ago by an asteroid impacting Earth.

Meteor Crater first came to the

attention of scientists after American settlers encountered it in the 19th

century. Daniel M. Barringer, mining

engineer and businessman, was one of the first people to suggest that the

crater was produced by a meteoroid impact.

In 1903, Barringer’s company staked a

mining claim on the land and received a land patent signed by Theodore

Roosevelt. This led to the crater also

being known as “Barringer Crater.”

Despite an attempt to make the crater

a public landmark, the crater remains privately owned by the Barringer family to the present day. The Lunar and Planetary Institute and the

American Museum of Natural History, proclaim it to be the “best preserved

meteorite crater on Earth.” It was

designated a national landmark in 1967.

Today,

Meteor Crater is a popular tourist attraction with roughly 270,000 visitors per

year. The crater is also an important

educational and research site. It was

used to train Apollo astronauts and continues to be an active training site for

astronauts.

Pat and I have visited all these

natural wonders in northern Arizona and have enjoyed and appreciated every one

of them

Sources

My principal sources include “Geography

of Arizona,” “Northern Arizona,” Colorado Plateau,” San Francisco Volcanic Field,” “ Sunset

Crater,” San Francisco Peaks,” Antelope Canyon,” “Monument Valley,” “Painted

Desert,” “Petrified Forest,” “ Canyon de Chelly,” “Window Rock,” and Meteor

Crater,” en.wikipedia.org; “Grand Canyon,” and Painted Desert,” britannica.com;

“San Francisco Peaks,” snowbowl.ski; “How Was the Geological Marvel That is

Antelope Canyon, Formed,” smorescience.com; “Exploring the Unique Geology of

Monument Valley,” goldensoftware.com; “Petrified Forest National Park,” earthtrekkers.com;

“NPS Geodiversity Atlas - Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Arizona,” nps.gov;

plus numerous other online sources.

Comments

Post a Comment