HISTORY105 - Movies in the USA: Part 1

I’ve always liked movies. I don’t watch anything on television these

days except for sports and movies and I still enjoy a theater movie once in a

while. After a little digging recently,

I found out that I didn’t know much about the early days of movies or their

history through today. So, I’m going to

write about the history of movies.

This is a big subject - so I’m

focusing on movie history in the USA, except for inventions in Europe that

contributed greatly to the development of movies. I’m also going to do this in two parts: After a short introduction, Part 1 will cover the early years of movies, 1830 to 1910;

the silent years, 1910 to 1927; and the sound era through the end of World War

II. Part 2 will cover the post-World-War

II trends; the transition to the 21st century; the status of movies

today; and finally, a look at the future of movies.

I will list my principal sources

at the end of Part 2.

Introduction

Movies (alternatively called motion pictures, films, or

cinema) are the illusion of movement by the recording and subsequent rapid

projection of many still photographic pictures on a screen. The illusion of films is based on the

optical phenomena known as persistence of vision and the phi phenomenon. The first of these causes the human brain to

retain images cast upon the retina of the eye for a fraction of a second beyond

their disappearance from the field of sight, while the latter creates apparent

movement between images when they succeed one another rapidly. Together these phenomena permit the

succession of still frames on a film strip to represent continuous movement

when projected at the proper speed.

Originally a product of 19th-century scientific

endeavor, movies have become a medium of mass entertainment and communication,

and today are a multi-billion-dollar industry.

However, competition, first with

television, and later with video streaming from the internet, has significantly

changed how movies are delivered.

Early Years: 1830 - 1910

Origins. Before

the invention of photography, a variety of optical toys exploited the

illusion of movement effect by mounting successive drawings of things in motion

on the face of a twirling disk (c. 1832) or inside a rotating drum (c. 1834).

Cranking this rotating drum made the figure in the drawing appear to dance.

Then, in

1839, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, a French painter, perfected the

positive photographic process known as daguerreotype, and

that same year the English scientist William Henry Fox

Talbot successfully demonstrated a negative photographic process

that allowed unlimited positive prints to be produced from each negative. As photography was refined over the next few

decades, it became possible to replace the drawings in the early optical toys

and devices with individually posed (phase of motion) photographs, a practice

that was widely and popularly carried out.

There would be no true motion

pictures, however, until live action could be photographed spontaneously and

simultaneously. This required a

reduction in exposure time from the hour or so necessary for the pioneer photographic

processes to the one-hundredth (and, ultimately, one-thousandth) of a second

achieved in 1870. It also required the

development of series photography by the British American photographer Eadweard

Muybridge.

Muybridge believed that at some point

in its gallop, a horse lifts all four hooves off the ground at the same time. Conventions of 19th-century

illustration suggested otherwise, and the movement itself occurred too rapidly

for perception by the naked eye. In

1877, Muybridge set up 12 cameras along a Sacramento racecourse, with wires

stretched across the track to operate their shutters. As a horse galloped down the track, its

hooves tripped each shutter individually to expose successive photograph of the

gallop; one of the photos showed all

four hooves off the ground at the same time, confirming Muybridge’s belief. When Muybridge later mounted these images on

a rotating disk and projected them on a screen through a magic lantern (early

projection device), they produced a “moving picture” of the horse at full

gallop as it had actually occurred in life.

Eadweard Muybridge’s photographs of a running horse.

The French

physiologist Étienne-Jules Marey took the first series photographs

with a single instrument in 1882. His camera could take 12 consecutive

frames a second, with all the frames recorded on the same picture. Using these pictures, he studied the motion of

horses, birds, dogs, sheep, donkeys, elephants, fish, microscopic creatures,

mollusks, insects, and reptiles.

Muybridge and Marey conducted their

work as scientific inquiry - not for entertainment purposes. They both extended existing technologies to

probe and analyze events that occurred beyond the threshold of human

perception.

In 1887, in Newark, New Jersey,

an Episcopalian minister named Hannibal Goodwin developed the idea of

using celluloid as a base for photographic emulsions. The inventor and industrialist George

Eastman began manufacturing celluloid roll film in 1889 at his plant

in Rochester, New York. This event

was crucial to the development of movies: series photography such as Marey’s

could employ glass plates or paper strip film because it recorded events of

short duration in a relatively small number of images, but movies

would inevitably find its subjects in longer, more complicated events,

requiring thousands of images, and therefore just the kind of flexible but

durable recording medium represented by celluloid. It remained for someone to combine the

principles embodied in the apparatuses of Muybridge and Marey with celluloid

strip film to arrive at a viable motion-picture camera.

Edison and the Lumière

Brothers. American inventor and businessman Thomas Edison invented the phonograph in 1877, and

it quickly became the most popular home-entertainment device of the

century. Seeking to provide a visual

accompaniment to the phonograph, Edison commissioned William

Dickson, a young

laboratory assistant, to invent a motion-picture camera in 1888. Building upon the work of Muybridge and

Marey, Dickson’s motion-picture camera produced regular motion of

the film strip through the camera, and employed an evenly perforated

celluloid film strip to ensure precise synchronization between the film strip

and the shutter.

Edison had Dickson design a type of

peep-show viewing device called the Kinetoscope, in which a

continuous 47-foot film loop ran on spools between an incandescent

lamp and a shutter for individual viewing.

Starting in 1894, Kinetoscopes were marketed commercially through the

firm of Raff and Gammon for $250 to $300 apiece. The Edison Company supplied films for the

Kinetoscopes that Raff and Gammon were installing in penny arcades, hotel

lobbies, amusement parks, and other such semipublic places.

Thomas Edison’s lab developed an early motion-picture camera and the Kinetoscope, a device for individual film viewing.

The syndicate of Maguire and Baucus

acquired the foreign rights to the Kinetoscope in 1894, and began to market the

machines. It was a Kinetoscope

exhibition in Paris that inspired the Lumière brothers, Auguste and Louis,

to invent in 1895 the first commercially viable projector.

Edison’s films initially featured subjects such as circus or

vaudeville acts that could be taken into a small studio to perform before an

inert camera, while early Lumière films were

mainly documentary views, or “actualities,” shot outdoors on

location. In both cases, however, the

films themselves were composed of a single unedited shot, emphasizing lifelike

movement; they contained little or no narrative content.

By 1896, Edison had developed his own

projector, the Vitascope, had brought projection to

the United States, and established the format for American film exhibition for

the next several years.

During this time, which has been

characterized as the “novelty period,” emphasis fell on the projection device

itself, and films achieved their main popularity as self-contained vaudeville

attractions. These films, whether they

were Edison-style theatrical variety shorts, or Lumière-style actualities, were

perceived by their original audiences not as motion pictures in the modern

sense of the term, but as “animated photographs” or “living pictures.”

During the novelty period, production

companies leased a complete film service of projector, operator, and shorts to

the vaudeville market as a single, self-contained package. Starting about 1897, however, manufacturers

began to sell both projectors and films to itinerant exhibitors, who traveled

with their programs from one temporary location (vaudeville theaters,

fairgrounds, circus tents, lyceums) to another, as the novelty of their films

wore off at a given site. This gave the

exhibitors a large measure of control over early film form, since they were

responsible for arranging the one-shot films purchased from the producers into

audience-pleasing programs.

By encouraging the practice of

traveling exhibitions, the American producers’ policy of outright

sales inhibited the development of permanent film theaters in the

United States until nearly a decade after their appearance in Europe,

where England and France had taken an early lead in both production

and exhibition.

Méliès and

Porter. The shift away from films as animated photographs to

films as stories, or narratives, began to take place about the turn of the

century and is most evident in the work of the French filmmaker Georges

Méliès. By 1902, he had produced the influential 30-scene

narrative Le

Voyage dans la Lune (A Trip to the Moon). Adapted from a novel by Jules Verne, it

was nearly one reel in length (about 825 feet, or 14 minutes). The first film to achieve

international distribution, A Trip to the Moon was an enormous popular success.

Edwin S. Porter, a freelance

projectionist and engineer, joined the Edison Company in 1900. For the next few years, he served as

director-cameraman for much of Edison’s film output, starting with simple

one-shot films and short multi-scene narratives based on political cartoons and

contemporary events.

Porter’s The Great Train Robbery, 1903, is widely acknowledged to be the first narrative film

to achieve continuity of action. The industry’s first spectacular

box-office success, The Great Train Robbery is credited with

establishing the realistic narrative.

(See a video of the film at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=In3mRDX0uqk)

The Great Train Robbery established the complete story narrative in films.

Early Growth of the Film Industry.

The popularity of The

Great Train Robbery encouraged investors and led to the establishment of

the first permanent film theaters across the U.S. With exponential growth, the number of

permanent film theaters in the United States grew from a mere handful in 1904

to between 8,000 and 10,000 by 1908. Running about 12 minutes, the film

also helped to boost standard film length toward one reel.

Permanent theaters showed

approximately an hour’s worth of films for an admission price of 5 to 10

cents. Originally identified with

working-class audiences, theaters appealed increasingly to the middle class as

the decade wore on, and they became associated with the rising popularity of

the story film.

By 1908, there were about 20

motion-picture production companies operating in the United States. These

companies formed the Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPC), pooling

the 16 most significant U.S. patents for motion-picture

technology and entering into an exclusive contract with

the Eastman Kodak Company for the supply of raw film stock.

The MPPC helped to stabilize the

American film industry during a period of unprecedented growth and change by

standardizing exhibition practice, increasing the efficiency of

distribution, and regularizing pricing in all three sectors.

The Silent Years: 1910 - 1927

Pre-World War I American Cinema. Multiple-reel films achieved public

acceptance with the smashing success of the three-and-one-half-reel The

Loves of Queen Elizabeth, imported in 1912, which starred Sarah

Bernhardt. In 1912 Enrico Guazzoni’s

nine-reel Italian super-spectacle Quo Vadis? (Whither Are You Going?) was road-shown

in legitimate theaters across the U.S. at a top admission price of

one dollar. The feature craze was on!

The entire American film industry soon

reorganized itself around the economics of the multiple-reel film; the effects

of this restructuring did much to give movies their characteristic modern form.

Producers increased their budgets to

provide high technical quality and elaborate productions. The new viewers also had a more refined sense

of comfort, which exhibitors quickly accommodated by replacing their storefronts

with large, elegantly appointed new theaters in the major urban centers. Known as “dream palaces” because of the

fantastic luxuriance of their interiors, these houses had to show features

rather than a program of shorts to attract large audiences at premium

prices. By 1916, there were more than

21,000 movie theaters in the United States.

A lavish movie theater of the 1910s.

In August 1912, the U.S. Justice

Department sued the MPPC for “restraint of trade” in violation of

the Sherman Antitrust Act. Delayed

by countersuits and by World War I, the government’s case was eventually

won, and the MPPC formally dissolved in 1918, although it hadn’t been operational

since 1914.

The rise and fall of the MPPC

was concurrent with the industry’s move to southern California from its primarily Eastern U.S. roots.

It was clear that what producers required was a new industrial center -

one with a temperate climate, a variety of scenery, and access to acting

talent. The American film industry selected

a Los Angeles suburb (originally a small industrial town)

called Hollywood. Attractions

included the temperate climate required for year-round filming; a wide range

of topography within a 50-mile radius of Hollywood, including

mountains, valleys, forests, lakes, islands, seacoast, and desert; the status

of Los Angeles as a professional theatrical center; the existence of a low tax

base; and the presence of cheap and plentiful labor and land. This latter factor enabled the newly arrived

production companies to buy up tens of thousands of acres of prime real estate

on which to locate their studios, standing sets, and backlots. By 1915, approximately 15,000 workers were

employed by the motion-picture industry in Hollywood, and more than 60% of

American movie production was centered there.

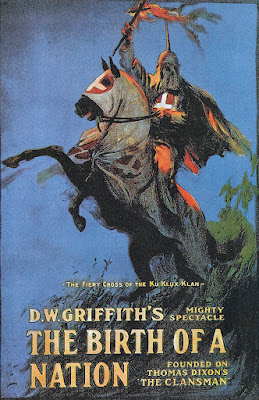

D. W. Griffith was the first director to complete a motion picture in Hollywood- In Old California was a 17-minute short melodrama about the Mexican era of California, made in 1910. From there, Griffith began experimenting with longer films until he successfully produced the first feature-length film in 1915, using twelve full reels of film, entitled Birth of a Nation. While this film was controversial in its own time, and even more problematic by today’s standards of equality and condemnation of racism and racial injustice, it also opened the industry to feature-length films and showcased exciting technical aspects of what filmmakers could achieve, such as close-ups, cross-cutting, fadeouts, and dramatic lighting. Most importantly, Griffith’s feature film proved America’s place as a leader in the most innovative filmmaking techniques.

Poster for The Birth of a Nation film.

Post-World War I American Cinema. During the 1920s in the United

States, motion-picture production, distribution, and exhibition became a major

national industry, and movies perhaps the major national obsession. The salaries of movie stars reached

monumental proportions; filmmaking practices and narrative formulas were

standardized to accommodate mass production; and Wall Street began to

invest heavily in every branch of the business.

The growing industry was organized

according to the studio system, where the head of the studio functioned as the

central authority over multiple production units, each headed by a director who

was required to shoot an assigned film according to a detailed

continuity script. Every project was

carefully budgeted and tightly scheduled. This central producer system was

the prototype for the studio system of the 1920s, and, with some

modification, it prevailed as the dominant mode of Hollywood production for the

next 40 years.

Virtually all the major

film genres evolved and were codified during the 1920s, but none was

more characteristic of the period than the slapstick comedy. This form was originated by Mack Sennett,

who, at his Keystone Studios, produced countless one- and

two-reel shorts and features whose narrative logic was subordinated to

fantastic, purely visual humor. A mixture

of circus, vaudeville, burlesque, pantomime, and the chase, Sennett’s Keystone

comedies created a world of inspired madness and mayhem, and they employed

the talents of such future stars as Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton,

Harold Lloyd, and Harry Langdon. After

these performers achieved fame, many of them left Keystone, often to form their

own production companies, a practice still possible in the early 1920s.

The “Big Four” of silent comedy: Charles Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, and Harry Langdon.

Chaplin, for example, who had

developed the persona of the “Little Tramp” at Keystone, went on to direct and

star in a series of shorts produced by Essanay in 1915 (including The Tramp)

and Mutual between 1916 and 1917 (including The Vagabond). In 1917, he was offered an eight-film

contract with First National that enabled him to establish his own studio. He directed his first feature there in 1921,

the semiautobiographical The Kid, but most of his First National

films were two-reelers.

In 1919, Chaplin, D.W.

Griffith, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks, the four most

popular and powerful film artists of the time, jointly formed the United

Artists Corporation to produce and distribute their own films - and

thereby retain artistic and financial control.

Chaplin directed three silent features for United Artists, including his

great comic epic The Gold Rush, 1925.

Buster Keaton possessed

a kind of comic talent very different from Chaplin’s, but both men were

wonderfully subtle actors with a keen sense of the tragic often

contained within the comic, and both were major directors of their period. In 1919, Keaton formed his own production

company, where over the next four years he made 20 shorts. A Keaton trademark was the “trajectory gag,”

in which perfect timing of acting, directing, and editing propels his film

character through a geometric progression of complicated sight gags that seem

impossibly dangerous but are still dramatically logical. Such routines inform all of Keaton’s major

features, including his masterpieces The General, 1927,

and Steamboat Bill, Jr., 1928.

Working at the Hal

Roach Studios, Lloyd cultivated the persona of an earnest,

sweet-tempered boy-next-door. He

specialized in a variant of Keystone mayhem known as the “comedy of thrills,”

in which - as in Lloyd’s most famous features, Safety Last!, 1923, and The Freshman, 1925 - an innocent protagonist finds

himself placed in physical danger.

Langdon traded on a childlike,

even babylike, image in such popular features as The Strong Man, 1926,

and Long Pants, 1927 - both directed by Frank Capra.

Important but lesser silent comics

were the team of Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, and Roscoe Arbuckle. Laurel and Hardy also worked

for Roach, making 27 silent two-reelers. Their comic characters were basically

grown-up children whose relationship was sometimes disturbingly

sadomasochistic.

Roscoe Conkling "Fatty" Arbuckle’s talent was limited, but his persona affected the course of American film history in a quite unexpected way. Arbuckle was at the center of the most damaging scandal to affect American motion pictures during the silent era. In September 1921, the comedian and several friends hosted a weekend party in a San Francisco hotel. During the party a young actress named Virginia Rappe became ill, and she later died in a hospital of peritonitis. Press reports of the event as a drunken orgy inflamed public opinion. Eventually indicted for manslaughter, Arbuckle was tried three times and eventually acquitted. But Arbuckle’s career as an actor was ruined, and he was banned from the screen for more than a decade.

Fatty Arbuckle was at the center of the most damaging scandal during the silent era.

To stave off increasing efforts by

state and local governments to censor films, the Hollywood studios formed a

new, stronger trade association, the Motion Picture Producers and

Distributors of America; later renamed the Motion Picture

Association of America. They also

hired a conservative politician, U.S. Postmaster General Will H. Hays, as

its head. The Hays Office, as the association became popularly known,

advocated industry self-regulation as an alternative to governmental

interference, and it succeeded in preventing the expansion of censorship

efforts. Hays promulgated a

series of documents that attempted to regulate various forms of criminal and

immoral behavior depicted in movies. A principle termed “compensating values,”

recognized that popular entertainment had always told stories of lawbreaking

and social transgression, but it held that law and morality should

always triumph in a film.

The leading practitioner of the

compensating values formula was the flamboyant director Cecil B.

DeMille. When the Hays Office was

established, DeMille turned to the sex- and violence-drenched religious

spectacles that made him an international figure, notably The Ten

Commandments, 1923. Also popular

during the 1920s, were the swashbuckling exploits of Douglas Fairbanks,

whose lavish adventure spectacles, including Robin Hood, 1922,

and The Thief of Bagdad, 1924, thrilled a generation.

The most enigmatic and

unconventional figure working in Hollywood at the time, however, was without a

doubt the Viennese émigré Erich von Stroheim. His first three films constitute an obsessive

trilogy of adultery; each features a sexual triangle in which an American wife

is seduced by a Prussian army officer.

Even though all three films were enormously popular, the great sums

Stroheim was spending on the extravagant production design and costuming of his

projects brought him into conflict with his Universal producers, and he was

replaced.

During the 1920s, the American film

industry transformed from a “no-hold-barred” entrepreneurial enterprise

into an industry that had no tolerance for creative difference. Stroheim’s situation was not unique; many

singular artists, including Griffith, Sennett, Chaplin, and Keaton, found it

difficult to survive as filmmakers under the rigidly standardized studio system

that had been established by the end of the decade.

The Sound Era Through World War II

Introduction of Sound. By the time the feature had become the

dominant film form in the U.S., producers

regularly commissioned orchestral scores to accompany prestigious

productions, and virtually all films were accompanied by cue sheets suggesting

appropriate musical selections for performance during exhibition.

Actual recorded sound became possible

only after Lee De Forest’s perfection in 1907 of a vacuum tube that

magnified sound and drove it through speakers so that it could be heard by a

large audience. Between 1923 and 1927,

he made more than 1,000 synchronized sound shorts for release to specially

wired theaters. The public was widely

interested in these films, but the major Hollywood producers, to whom De Forest

vainly tried to sell his system, were not: they viewed “talking pictures” as an

expensive novelty with little potential return.

In 1925, Western Electric, the

manufacturing subsidiary of American Telephone & Telegraph Company,

perfected a sophisticated sound-on-disc system called Vitaphone, which

De Forest attempted to market to Hollywood. Like De Forest, he was rebuffed by the major

studios, but Warner Brothers, then a minor studio in the midst of

aggressive expansion, bought both the sound system and the right to sublease it

to other producers. The studio planned

to use Vitaphone to provide synchronized orchestral accompaniment for all

Warner Brothers films, thereby enhancing their marketability to

second- and third-run exhibitors who could not afford to hire live orchestral

accompaniment. Warner Brothers debuted the system on August

6, 1926, with Don Juan, a lavish costume drama starring John

Barrymore, directed by Aanl Crosland, and featuring a score performed by

the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. The

response was enthusiastic; Warner Brothers announced that all its films for

1927 would be released with synchronized musical accompaniment and then turned

immediately to the production of its groundbreaking second Vitaphone

feature.

The Jazz Singer,1927,

starring Al Jolson, also directed by Crosland, included not only popular songs,

but incidental dialogue in

addition to the orchestral score; its phenomenal success as the first sound

movie virtually ensured the industry’s conversion to sound.

Poster for the world’s first movie with sound, The Jazz Singer, 1927.

Competition in sound systems led to a sound-on-film

system that eventually prevailed over sound-on-disc because it enabled image

and sound to be recorded simultaneously in the same (photographic) medium,

ensuring their precise and automatic synchronization.

The wholesale conversion to sound took

place in fewer than 15 months, between late 1927 and 1929, and the profits of

the major companies increased during that period by as much as 600%. Although the transition was fast,

orderly, and profitable, it was also enormously expensive. The industrial system, as it had evolved for

the previous three decades, needed to be completely overhauled; studios and

theaters had to be totally reequipped and creative personnel retrained or

fired.

There were many technical problems,

including standardizing equipment, poorly performing early microphones, and

editing film containing recorded sound. Most

of these technical problems were resolved by 1933.

The technological development that

most liberated the sound film, however, was the practice known variously

as postsynchronization, rerecording, or dubbing, in which image and sound

are printed on separate pieces of film so that they can be manipulated

independently. Postsynchronization

enabled filmmakers to edit images freely again. Because the overwhelming emphasis of the

period from 1928 to 1931 had been on obtaining high-quality sound in

production, however, the idea that the sound track could be modified

after it was recorded took a while to catch on.

In 1933, however, technology was

introduced that allowed filmmakers to mix separately recorded tracks for

background music, sound effects, and synchronized dialogue. By the late 1930s, postsynchronization and

multiple-channel mixing had become standard industry procedure.

Other changes wrought by sound were

more purely human. Directors, for

example, could no longer literally direct their performers while the cameras

were rolling and sound was being recorded. Actors and actresses were suddenly required to

have pleasant voices, memorize their lines, and to act without the assistance

of mood music or the director’s shouted instructions through long dialogue

takes.

Many actors found that they could not

learn lines; others tried and were defeated by heavy foreign accents or voices

that did not match their screen images. Numerous

silent stars were supplanted during the transitional sound period by stage

actors or film actors with stage experience.

Sound also created

new genres and renovated old ones. The realism it permitted inspired the

emergence of tough, socially pertinent films with urban settings, including gangster

films that highlighted gunfire and vernacular speech. The public’s fascination with speech

also accounted for the new popularity of historical biographies, or “biopics.” In the realm of comedy, pure slapstick could

not, and did not survive, predicated as it was on purely visual

humor. It was replaced by equally vital

- but ultimately less bizarre and abstract - sound comedies. The horror-fantasy genre was also greatly

enhanced by sound, which permitted the addition of eerie sound effects.

One significant genre whose emergence

was obviously contingent upon

sound was the musical. Versions of

Broadway musicals were among the first sound films made. By the early 1930s, the movie musical had

developed to become perhaps the major American genre of the decade.

Introduction

of Color. Photographic color entered the movies at

approximately the same time as sound. As with sound, various color effects had

been used in films since the invention of the medium, including hand-coloring

of films frame by frame.

By the early 1920s, nearly all U.S.

features included at least one colored sequence; but after 1927, when it was

discovered that tinting film stock interfered with

the transmission of recorded sound, this practice was abandoned,

leaving the market open to new systems of color photography.

In 1932, Technicolor Corporation

introduced a three-color dye-transfer process that made it possible to

mass-produce sturdy, high-quality prints onto a single strip of film, that

included all three primary colors.

For the next 25 years, almost every

color film made was produced by using Technicolor’s three-color system. Although the quality of the system was

excellent, there were drawbacks. The

bulk of the camera made location shooting difficult. Furthermore, Technicolor’s

virtual monopoly gave it indirect control of the production

companies, which were required to rent - at high rates - equipment, crew,

consultants, and laboratory services from Technicolor every time they used the

system.

The Wizard of Oz, 1939, was not the first movie in color, but it revolutionized the use of color in film and set a precedent for future movies.

The Hollywood Studio System. If the coming of sound changed

the aesthetic dynamics of the filmmaking process, it altered the

economic structure of the industry even more, precipitating some of the largest

mergers in motion-picture history.

By 1930, 95% of all American movie production

was concentrated in the hands of only eight studios which controlled

production, distribution, and exhibition.

The five major studios were MGM, Paramount, Warner Brothers, Twentieth

Century-Fox, and RKO. The minor studios were

Universal Pictures, Columbia Pictures, and United Artists.

At the very bottom of the film

industry hierarchy were a score of poorly capitalized studios, such

as Republic, Monogram, and Grand National, that produced cheap

formulaic hour-long “B movies” for the second half of double bills. The double feature, an attraction

introduced in the early 1930s to counter the Depression-era box-office

slump, was the standard form of exhibition for about 15 years. At their peak, the B-film studios produced 40-50 movies

per year, and provided a training ground for such stars as John Wayne. The films were made as quickly as possible,

and directors functioned as their own producers, with complete authority over

their projects’ minuscule budgets.

Distribution was conducted at both a

national and an international level: since about 1925, foreign rentals had

accounted for half of all American feature revenues, and they would continue to

do so for the next two decades. Exhibition

was controlled through the major studios’ ownership of 2,600 first-run

theaters, which represented 16% of the national total, but generated

three-fourths of the revenue.

An important aspect of the studio

system was the Production Code, which was implemented in 1934 in

response to pressure from the Legion of Decency and public protest against

the graphic violence and sexual suggestiveness of some sound films (the urban

gangster films, for example, and the films of Mae West). The Production Code dictated the content of

American movies, without exception, for the next 20 years.

The Production Code was monumentally

repressive, forbidding the depiction on-screen of clearly-specified aspects of almost

everything germane to the experience of normal human adults, including

violence, sex, drug addiction, profanity, racial epithets, excessive drinking,

and cruelty to children or animals. Noncompliance

with the Code’s restrictions brought a fine of $25,000, but the studios were so

eager to please that the fine was never levied in the 22-year lifetime of the Code.

Between 1930 and the end of World War

II, the studio system produced more than 7,500 features, every stage of which,

from conception through exhibition, was carefully controlled. Among these assembly-line productions are some

of the most important American films ever made, the work of gifted directors

who managed to transcend the mechanistic nature of the system to

produce work of unique personal vision. Those directors included Josef von

Sternberg, whose exotically stylized films starring Marlene Dietrich, Shanghai

Express, 1932, and The Scarlet Empress, 1934, constitute a

kind of painting with light; John Ford, whose vision of history

as moral truth produced such mythic works as Stagecoach, 1939, Young

Mr. Lincoln, 1939, The Grapes of Wrath, 1940, and My

Darling Clementine, 1946; Howard Hawks, a master

of genres and the architect of a tough, functional “American” style

of narrative exemplified in his films Scarface, 1932, and The

Big Sleep, 1946; British émigré Alfred Hitchcock, whose films appealed

to the popular audience as suspense melodramas, including Rebecca, 1940, Suspicion, 1941, Shadow of a Doubt,

1943, and Notorious, 1946; and Frank Capra, whose cheerful

screwball comedies, It Happened One Night, 1934,

and populist fantasies of good will, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,

1939, sometimes gave way to darker warnings against losing faith

and integrity, e.g., It’s a Wonderful Life, 1946. Other significant directors with

less-consistent thematic or visual styles were William Wyler, Wuthering

Heights, 1939, and The Little Foxes, 1941; George Cukor, Camille,

1936, and The Philadelphia Story, 1940; Leo McCarey, The

Awful Truth, 1937, and Going My Way, 1944; Preston Sturges,

Sullivan’s Travels, 1941, and The Miracle of

Morgan’s Creek, 1944; and George Stevens, Gunga Din, 1939, and

Woman of the Year, 1942.

The most extraordinary film to emerge

from the studio system, however, was Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane,

1941, whose controversial theme and experimental technique combined to make it

a classic. The quasi-biographical

film examines the life and legacy of Charles Foster Kane, played by

Welles, a composite character based on American media

barons William Randolph

Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer.

Citizen Kane, 1941, on several occasions, has been voted the best movie all time.

Special World War II Movies. During the U.S. involvement in World War II, the Hollywood film industry cooperated closely with the government to support its war-aims information campaign. Following the declaration of war on Japan, the government created a Bureau of Motion Picture Affairs to coordinate the production of entertainment features with patriotic, morale-boosting themes and messages about the “American way of life,” the nature of the enemy and the allies, civilian responsibility on the home front, and the fighting forces themselves.

In addition to commercial features, several Hollywood

directors produced documentaries for government and military agencies. Among the best-known of these films, which

were designed to explain the war to both servicemen and civilians,

are Frank Capra’s seven-part series Why We Fight,

1942–44; John Ford’s The Battle of Midway,1942; William

Wyler’s The Memphis Belle, 1944; and John Huston’s The

Battle of San Pietro, 1944.

See my next blog, The History of Movies in the USA: Part 2

Comments

Post a Comment