History106 - Movies in the USA: Part 2

This blog is Part 2 of my two-part series on the history

of movies in the USA. Part 1 covered the

early years of movies, 1830 to 1910; the silent years, 1910 to 1927; and the sound

era through World War II. Part 2 will

cover post-World-War-II trends through 1980; the transition to the 21st

century; the status of movies today; and finally, a look at the future of

movies.

I will list my principal sources for both Part 1 and Part

2 at the end.

Post-World-War-II

Trends Through 1980

Decline

of the Hollywood Studios. When World War II ended, the American film industry

seemed to be in an ideal position.

Full-scale mobilization had ended the Depression domestically, and

victory had opened vast, unchallenged markets in the war-torn economies

of western Europe and Japan. Furthermore, from 1942 through 1945, Hollywood had experienced the most

stable and lucrative three years in its history, and in 1946, when two-thirds

of the American population went to the movies at least once a week, the studios

earned record-breaking profits.

The euphoria ended quickly, however, as inflation and labor unrest boosted domestic production costs. The industry was more severely weakened in 1948, when a federal antitrust suit against the five major and three minor studios ended in the “Paramount decrees,” which forced the studios to divest themselves of their theater chains and mandated competition in the exhibition sector for the first time in 30 years. Finally, the advent of network television broadcasting in the 1940s provided Hollywood with its first real competition for American leisure time by offering consumers “movies in the home.”

The

American film industry’s various problems, and the nation’s general postwar

disillusionment generated several new film types in the late 1940s. Although the studios continued to produce

traditional genre films, such as westerns and musicals, their

financial difficulties encouraged them to make realistic small-scale dramas

rather than fantastic lavish epics.

Instead of depending on spectacle and special effects to

create excitement, the new lower-budget films tried to develop

thought-provoking or perverse stories reflecting the psychological and social

problems besetting returning war veterans and others adapting to postwar

life. Examples include The Lost

Weekend, 1945, treating alcoholism; Gentleman’s Agreement, 1947,

involving anti-Semitism; The Snakepit,1948, a study of mental illness;

and Pinky,1949, about racism in the Deep South.

The

Fear of Communism. Film content was

next influenced strongly by the fear of communism that pervaded

the United States during the late 1940s and early 1950s. Anticommunist “witch-hunts” began in

Hollywood in 1947 when the House Un-American Activities

Committee (HUAC) decided to investigate communist influence in

movies. More than 100 witnesses,

including many of Hollywood’s most talented and popular artists, were called

before the committee to answer questions about their own and their

associates alleged communist affiliations. On November 24, 1947, a group of eight

screenwriters and two directors, who came to be known as the Hollywood Ten,

were sentenced to serve up to a year in prison for refusing to testify. That evening the members of the Association

of Motion Picture Producers, which included the leading studio heads, published

what became known as the Waldorf Declaration, in which they fired the

members of the Hollywood Ten and expressed their support of HUAC.

The

studios, afraid to antagonize already shrinking audiences, then initiated an

unofficial policy of blacklisting, refusing to employ any person even

suspected of having communist associations.

Hundreds of people were fired from the industry, and many creative

artists were never able to work in Hollywood again. Throughout the blacklisting era, filmmakers

refrained from making any but the most conservative motion pictures;

controversial topics or new ideas were carefully avoided. The resulting creative stagnation, combined

with financial difficulties, contributed significantly to the decline of

the studio system.

|

| Protesters demonstrating against the arrest of the Hollywood Ten. |

The

Threat of Television. The greatest threat to the film industry’s continued

success was posed by television.

Note: The opening of the 1939 World’s Fair in New

York introduced television to a national audience. NBC soon began nightly broadcasts. As black-and-white TVs became more common in

American households, the finishing touches on color TV were refined in the late

1940s. By the 1950s, television had

truly entered the mainstream, with more than half of all American homes

owning TV sets by 1955. Improvements in TV continued rapidly, including cable

television (1948), video tape (1956), satellite TV (1962), video recording

(1976), and high-definition TV (1981).

The

studios were losing control of the nation’s theaters, while exhibitors, the

people who owned the movie screens, were losing audiences to television. The studios therefore attempted

to diminish black and white television’s appeal by exploiting three

obvious advantages that film enjoyed over the new medium - the size of its

images, the ability to produce photographic color, and stereophonic sound,

introduced in 1952.

|

| Television had the greatest negative impact on movie attendance. |

In

1950, Kodak introduced a new multilayered film stock in which emulsions

sensitive to the red, green, and blue parts of the spectrum were bonded

together on a single roll. Patented as Eastmancolor, this

“integral tri-pack” process offered excellent color resolution at a low cost

because it could be used with conventional cameras. Its availability hastened the industry’s

conversion to full color production. By

1954, more than 50% of American features were made in color, and the figure

reached 94% by 1970.

The aspect

ratio (the ratio of width to height) of the projected motion-picture image

had been standardized at 1.33 to 1 since 1932, but, as television eroded the

film industry’s domestic audience, the studios increased screen size as a way

of attracting audiences back into theaters.

Early

experiments with wide-screen Cinerama, 1952, and stereoscopic 3-D, 1952, stimulated audience

interest, but it was CinemaScope that prompted the wide-screen

revolution. Introduced by Twentieth

Century-Fox in the biblical epic The Robe,1953, CinemaScope’s wide-screen

aspect ratio was 2.55 to 1. The system

had the great advantage of requiring no special cameras, film stock, or

projectors. By the end of 1954, every

Hollywood studio but Paramount had leased a version of the

CinemaScope process from Fox.

Like

the coming of sound, the conversion to wide-screen formats produced problems

initially as filmmakers learned how to compose and edit their images for the

new elongated frame. Sound had promoted

the rise of aurally intensive genres such as the musical and the

gangster film, and the wide-screen format similarly created a bias in favor of

visually spectacular subjects and epic scale.

The emergence of the three- to four-hour wide-screen “blockbuster” in

such films as War and Peace, Around the World in Eighty

Days, and The Ten Commandments in 1956 coincided with the

era’s affinity for safe and sanitized material. Given the political paranoia of the times,

few subjects could be treated seriously, and the studios concentrated on

presenting traditional genre fare - westerns, musicals, comedies, and

blockbusters - suitable for wide-screen treatment. Only a director like Hitchcock, whose

style was unique could buck the trend in such a climate. He produced his greatest works during the

period, Rear Window, 1954, The Man Who

Knew Too Much, 1956, Vertigo, 1958, North by

Northwest, 1959, Psycho, 1960, and The Birds, 1963.

In

spite of the major film companies elaborate strategies of defense, they

continued to decline throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Because they could no longer own theaters,

they faced serious competition for the first time from independent and

foreign filmmakers. “Runaway”

productions (films made away from the studios, frequently abroad, to take

advantage of lower costs) became common.

The Production Code, implemented in 1934 to police graphic violence

and sexual suggestiveness, was dissolved in a series of federal

court decisions between 1952 and 1958 to extended First

Amendment protection to motion pictures.

As their incomes shrank, the major companies’ vast studios and backlots

became liabilities that ultimately crippled them. The minor companies, however, owned modest

studio facilities and had lost nothing by the 1948 Paramount decrees because

they controlled no theaters. They were

thus able to prosper during this era, eventually becoming major companies

themselves in the 1970s.

The

Youth Cult and Other Trends. The

years 1967-69 marked a turning point in American film history as Penn’s Bonnie

and Clyde, 1967; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey,

1968; Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch, 1969; Wexler’s Medium

Cool, 1969; and Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider, 1969;

attracted the youth market to theaters in record numbers. Altman’s M*A*S*H, 1970, provided

a novel comedic coda to the quintet.

These films all shared a cynicism toward established values

and a fascination with violence. Artistically,

the films domesticated New Wave editing techniques, enabling once-radical

practices to enter the mainstream narrative cinema. Financially, they were so successful, that

producers quickly saturated the market with low-budget youth-culture movies,

only a few of which achieved even limited distinction.

|

| Films like Easy Rider attracted the youth market to theaters. |

Concurrent with

the youth-cult boom was the new permissiveness toward sex, made possible by the

institution of the Motion Picture

Association of America (MPAA)

ratings system in 1968. Unlike the

Production Code, this system of self-regulation did not prescribe the content

of films but categorized them according to their appropriateness for young

viewers:

G designated general

audiences; PG suggested parental guidance; PG-13 strongly cautioned parents

because the film contained material inappropriate for children under 13; R

indicated that the film was restricted to adults and to persons under 17

accompanied by a parent or guardian; and X or NC-17 signified that no one under

17 could be admitted to the film - NC meaning “no children.

In

practice, the X rating has usually been given only to unabashed pornography and

the G rating to children’s films, which has had the effect of concentrating

sexually explicit but serious films in the R and NC-17 categories. The introduction of the ratings system led

immediately to the production of serious, nonexploitative adult films, such

as John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy, 1969, and Mike

Nichols’s Carnal Knowledge, 1971, in which sexuality was treated

with a maturity and realism unprecedented on the American screen.

Despite

increasing costs, the unprecedented popularity of a few films like Francis Ford

Coppola’s The Godfather, 1972; Steven Spielberg’s Jaws,

1975; and George Lucas’s Star Wars, 1977, produced enormous

profits and stimulated a wildcat mentality within the industry. In this environment, it was not uncommon

for the major companies to invest their working capital in the production of

only five or six films a year, hoping that one or two would be extremely

successful. At one

point, Columbia reputedly had all its assets invested in

Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind, 1977, a gamble that

paid off handsomely; United Artists’ similar investment in Michael Cimino’s

financially disastrous Heaven’s Gate, 1980, however, led to the

sale of the company and its virtual destruction as a corporate entity.

|

| Films like Easy Rider attracted the youth market to theaters. |

The

new generation of directors that came to prominence at this time included many

who had been trained in university film schools: Francis Ford Coppola, Paul

Schrader, Martin

Scorsese, Brian De Palma, and Steven Spielberg - as well as others who had been

documentarians and critics before making their first features: Peter

Bogdanovich, and William Friedkin.

These filmmakers brought to their work a technical sophistication and a

sense of film history eminently suited to the new Hollywood, whose quest for

enormously profitable films demanded slick professionalism and a thorough

understanding of popular genres.

The

graphic representation of violence and sex, which had been pioneered with risk

by Bonnie and Clyde, The Wild Bunch, and Midnight

Cowboy in the late 1960s, was exploited for its sensational effect

during the 1970s in such well-produced R-rated features as Coppola’s The

Godfather, Friedkin’s The Exorcist, Spielberg’s Jaws,

Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, De Palma’s Carrie, and scores

of lesser films. The newly popular

science-fiction/adventure genre was similarly supercharged through

computer-enhanced special effects and Dolby sound as the brooding

philosophical musings of Kubrick’s 2001 gave way to the

cartoon-strip violence of Lucas’s Star Wars, Spielberg’s Raiders

of the Lost Ark, and their myriad sequels and copies.

There

was, however, originality in the 1970s in the continuing work of Altman’s McCabe

and Mrs. Miller, Nashville and Three Women; and

Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange and The Shining; American

Film Institute graduate Terrence Malick’s Badlands, Days

of Heaven; and controversial newcomer Cimino’s The Deerhunter

and Heaven’s Gate. In

addition, Coppola’s The Godfather, The Godfather, Part II,

and Apocalypse Now; and Scorsese’s Mean Streets and Raging

Bull created films of unassailable importance.

|

| Coppola’s Godfather movies were important films of the 1970s. |

Some

of the strongest films of the era came from émigré directors working within the

American industry - John Boorman’s Deliverance, Roman Polanski’s Chinatown, Miloš

Forman’s One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and Ridley

Scott’s Alien. In general,

however, Hollywood’s new corporate managers lacked the judgment of industry

veterans and tended to rely on the recently tried and true (producing an

unprecedented number of high-budget sequels) and the viscerally sensational.

To

this latter category belonged the spate of “psycho-slasher” films that glutted

the market in the wake of John Carpenter’s highly successful

low-budget chiller Halloween. The slasher films took the gore and

violence into the mainstream of Hollywood films.

Transition to 21st Century: 1980 - 2019

During

the 1980s the fortunes of the American film industry were increasingly shaped

by new technologies of video delivery and imaging. Cable networks, direct-broadcast satellites,

and half-inch videocassettes provided new means of motion-picture distribution,

and computer-generated graphics provided new means of production,

especially of special effects, forecasting the prospect of a fully automated

“electronic cinema.”

In

1985, for the first time since the 1910s, independent film producers

released more motion pictures than the major studios, largely to satisfy the

demands of the cable and home-video markets

The

strength of the cable and video industries led producers to seek properties

with video or “televisual” features that would play well on the small

television screen or to attempt to draw audiences into the theaters with the

promise of spectacular 70-mm photography and multitrack Dolby sound.

Ironically,

the long-standing 35-mm theatrical feature survived in the mid-1980s in such

unexpected places as “kidpix” (a form originally created to exploit the PG-13

rating when it was instituted in 1984) - The Breakfast Club, and Stand

by Me, and, more dramatically, the Vietnam combat film, Oliver

Stone’s Platoon, Coppola’s Gardens of Stone, and

Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket.

Responding to the political climate, the studios produced some of their

most jingoistic films since the Korean War, endorsing the notion

of political betrayal in Vietnam with Rambo and First Blood, Part II;

fear of a Soviet invasion, Red Dawn; and military vigilantism, Top

Gun. Films with a “literary”

quality, many of them British-made, were also popular in the American market

during the 1980s - A Passage to India, A Room with a View,

and Out of Africa.

In

the last 20 years of the 20th century and the early years of the 21st

century, the idea of “synergy” dominated the motion-picture industry in the

United States, and an unprecedented wave of mergers and acquisitions

occurred. Synergy means consolidating

related media and entertainment properties under a single umbrella to strengthen

every facet of a coordinated communications empire. Motion pictures, broadcast television, cable

and satellite systems, radio networks, theme parks, newspapers and magazines,

book publishers, manufacturers of home entertainment products, sports teams, internet

service providers - these were among the different elements that came together

in various corporate combinations under the notion that each would boost the

others.

News

Corporation Ltd., originally an Australian media company, started the

trend by acquiring Twentieth Century-Fox in 1985. The Japanese manufacturing

giant Sony

Corporation acquired

Columbia Pictures Entertainment, Inc. from The Coca-Cola Company in 1989. Another Japanese firm, Matsushita, purchased

Universal Studios (as part of Music Corporation of America) in 1990; it

then was acquired by Seagram Company Ltd. In 1995, became

part of Vivendi Universal Entertainment in 2000, and merged with the National

Broadcasting Co., Inc. 2004 as a subsidiary of the Comcast Corporation.

Paramount Pictures, as Paramount Communications, Inc., became part of

Viacom Inc. In perhaps the most striking

of all ventures, Warner Communications merged with Time Inc. to

become Time Warner Inc., which in turn came together with the Internet

company America Online (AOL) to form AOL Time Warner in 2001. The company then changed its name again, back

to Time Warner Inc. in 2003; it was purchased by AT&T in 2018 and renamed

WarnerMedia. The Disney Company became an acquirer,

adding Miramax Films, the television network American Broadcasting

Company, the cable sports network ESPN, and, in 2019, 20th Century-Fox,

among other properties.

In

part, through the expensive and lavish effects attained through the new

technologies, American cinema at the end of the 20th century

sustained and even widened its domination of the world film marketplace. Exhibition outlets continued to grow, with

new “megaplex” theaters offering several dozen cinemas, while distribution

strategies called for opening major commercial films on 1,000 or more -

sometimes as many as 3,000 by the late 1990s - screens across the country.

Meanwhile

major advances in computer-generated imagery and special effects

allowed for films of unprecedented visual sophistication - Jurassic Park, Star

Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Menace, and The Matrix; audiences

preferred the experience of seeing such films on large theater screens. Computer animation was also put to

good use in films that play equally well on theater or television screens, such

as Toy Story, Antz, and Chicken Run.

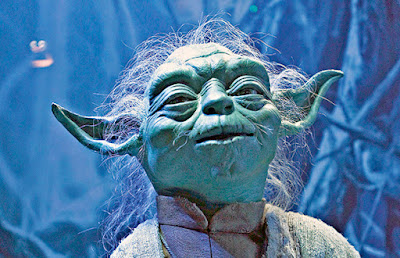

|

| The famous computer-generated animated character Yoda in Star Wars films. |

The

motion-picture industry’s continuing emphasis on pleasing the youth audience

with special effects-laden blockbusters, and genre works such as

teen-oriented horror films and comedies inevitably diminished the role of

directors as dominant figures in the creative process. Still, more than a handful of filmmakers,

several of them veterans of an earlier era, maintained

their prestige.

Two

of the most prominent, who had launched their careers in the early 1970s,

were Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese. In addition to Jurassic Park,

Spielberg’s works in the 1990s included Schindler’s List, Amistad,

and Saving Private Ryan; with A.I. Artificial Intelligence,

Munich, Lincoln, and Bridge of Spies among his

subsequent films. Scorsese

directed GoodFellas, The Age of innocence, Casino, Kundun,

Gangs of New York, The Departed, and The Irishman.

The

actor-director Clint Eastwood was also prolific in this

period, winning the best picture Academy Award with Unforgiven in

1992, and directing such other films as Mystic River, Million

Dollar Baby, Letters from

Iwo Jima, Gran Torino, Invictus, American

Sniper, Sully and The Mule.

A

succeeding generation of filmmakers who could claim the status of master

directors included such figures as David Lynch, Oliver

Stone, James Cameron, Christopher Nolan, and Spike Lee. Lynch’s work included Mulholland

Drive in

2001. Stone is best known for

politically oriented films such as Nixon in 1995. Cameron’s Titanic, re-creating

the 1912 sinking of an ocean liner on its

maiden voyage after striking an iceberg, won an Academy Award in 1997

for best picture, and broke domestic and worldwide box-office records. Cameron also created an immersive new world

in the fantasy adventure Avatar in 2009. The British-American Nolan directed the Dark

Knight trilogy Batman Begins, The Dark

Knight, and The Dark

Knight Rises. Lee, the most prominent among a group of young African

American filmmakers, directed Malcolm X.

|

| James Cameron’s Titanic won an Academy Award in 1997 for best picture and broke domestic and worldwide box-office records. |

A

notable development in American cinema was the rise of significant female

filmmakers, including Kathryn Bigelow, Patty Jenkins, and Sofia

Coppola. Bigelow’s

accomplished Iraq War drama The Hurt Locker made her the

first woman to win an Academy Award for best director, and it also

received an Oscar for best picture. Jenkins staked out a claim on superhero

movies, directing Wonder Woman and Wonder Woman

1984. Coppola

is the daughter of Francis Ford Coppola; her screenwriting for Lost in

Translation earned her an

Oscar, and she became the first American woman to be nominated for best

director and received the Golden Lion for best film at Venice, and took the

award for best director at Cannes for her Civil War thriller The Beguiled.

Another

significant development in late 20th-century American cinema was the

emergence of an independent film movement. Organizations such as the

Independent Feature Project and the Sundance Film Festival in Park

City, Utah, were founded to encourage and promote independent work. A major breakthrough was achieved when an American independent film, sex, lies and

videotape, the first feature by Steven Soderbergh, won the top prize

at the Cannes festival in 1989 in France.

|

| An American independent film - sex, lies and videotape - won the top prize at the Cannes festival in 1989. |

Independent

producers created some of the most unconventional and interesting work the

American cinema had seen in some time; they included the Coen

brothers’ Blood Simple, Fargo, O Brother, Where

Art Thou?; Spike Jonze’s Being John Malkovich and Adaptation;

and Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction and Jackie Brown. It was also an era in which low-cost

marketing via the Internet could turn a $50,000 independent film into

a $100,000,000 blockbuster like The Blair Witch Project.

The

independent movement also fostered what came to be called niche filmmaking,

which generated works growing out of ethnic and identity movements in

contemporary American culture.

Among these were films by African American, Native American,

and Latinx filmmakers, as well as works representing feminist and gay

and lesbian cultural viewpoints and experience.

Documentary filmmaking from these and other perspectives also thrived in

the independent world.

The Movie Industry Today

Theater

attendance essentially plateaued from 1995 to 2019. Meanwhile, ticket

prices increased, with the average ticket price in the U.S. growing from $5.39

in 2000 to $9.16 in $2019. The U.S. movie industry, a testament to

resilience, has withstood the test of time, enduring through Influenza,

diseases, and two World Wars.

|

| The popularity of movie genres over the years. |

Before

the pandemic in 2020/2021, most people went

to the movies at least once every two months.

There was no Disney+, no HBOMAX…only Netflix and Prime Video. But even then, those two weren't that much

used by subscribers or even well-known yet.

In 2019, over nine films made over a billion dollars at the theater box

office, which totaled $11.4 billion - times were pretty good, if not great, for

movies.

Then,

COVID happened, and that all changed.

The global health crisis, spanning two years, brought the industry to a

temporary halt. Box office income

plummeted. People

flocked to streaming services like crazy.

For example, Netflix went from 167M subscribers in late 2019 to 221M by

early 2021.

|

| Theater movie ticket sales plummeted during the Pandemic. |

With the rise of streaming services, most notably Disney

Plus, which promised viewers movies just months after their theatrical release,

audiences required good reasons to see a movie in theaters, rather than waiting

to watch it in the comfort of their own homes.

This worsened when movies demanded viewers to have watched shows or

multiple other previous movies.

After

a terrible 2020, and a slightly better - but still very bad 2021 - the year

2022 marked a massive return to form for theater movies, with huge juggernauts

that year, such as Spider-Man No Way Home, The Batman, Minions,

Everything, and Everywhere All at Once.

However,

there were still two problems in 2022: audiences were coming back strong, but

the "over 45 years old" crowd was still skeptical about returning,

and certain studios were releasing films "day and day" - meaning they

were releasing them in theaters and on streaming services the same day. So, because of this, besides the success of

"superhero flicks," other movies weren't doing so well.

The

arrival of Top Gun: Maverick in summer 2022 changed everything

again. It became one of the

highest-grossing movies of all time, brought every single demographic to the

theater that entire summer, and made every studio realize that the "day

and day" strategy was nonsense.

Audiences still craved the theatrical experience. James Cameron's Avatar 2 in December

made $2.3B worldwide, the third highest-grossing film ever. The industry was

back on its feet now. Or at least it seemed like it…

But

2023 changed things up again. That year saw 14 over-200 million-dollar budgeted

movies alone. However, few were able to

turn a profit. Almost every

big-franchise movie was flopping as it hit theaters. Some examples are - Transformers, Mission

Impossible, Ant-Man, The Flash, Indiana Jones, and Fast

X. This shows the audience’s desire for

quality and ingenuity over just another old installment in a franchise.

The

industry got worried again until the massive, unexpected pop culture phenomenon

that was BARBENHEIMER happened in late July and took the world by

storm.

Barbie, the fantasy of a doll’s self- discovery, directed by

actor/filmmaker Greta Gerwig, made over $1.4 billion, and Christopher Nolan's

biopic of a nuclear scientist, Oppenheimer, made a shocking $975 million

- as a three-hour film without blockbuster action.

|

| The phenomenon of BARBENHEIMER, the simultaneous release of two wildly successful movies in 2023, Barbie and Oppenheimer, buoyed the theater film industry. |

To

the people still preferring to wait for streaming, these two movies changed

that mindset for many moviegoers. Ticket

attendance started to go up like crazy, and so did the box office, of

course. People were running to the

theaters all over the globe for these two movies. These were "event films.” Everyone wanted to participate in the

conversation on Monday at work, school, or wherever. Streaming just couldn’t

offer that special feeling.

Today,

other than blockbuster event films, most people see movies on television,

whether cable, satellite, or subscription video on demand services. Streaming film content on computers, tablets,

and mobile phones is becoming more common as it proves to be more convenient

for modern audiences and lifestyles.

Most

mainstream productions are now shot on digital formats with subsequent

processes, such as editing and special effects, undertaken on computers.

Cinemas have

invested in digital projection facilities capable of producing screen images

that rival the sharpness, detail, and brightness of traditional film projection. Only a small number of more specialist

cinemas have retained film projection equipment.

The

over decline of theater movies is not attributable to the movie-going

experience, as most exhibitors have invested heavily in improvements, including

new audio-visual systems, more comfortable seating, and expansive dining

options. Admission declines have chiefly

resulted from the monolithic nature of the studio film pipeline, which is full

of comic book fare, juvenile action films, message-over-substance titles, and

the deterioration of shared cultural heritage in the West.

Many

Streaming Video on Demand services are now owned (or supported by) major

studios, which reduces the incentive for long runs in theaters, and intensifies

an increasingly competitive streaming environment. Some studios, armed with their own streaming

services and cable platforms, skip the theater altogether.

But with all of that said, the magical experience of cinema

is not dead. There are still studios, directors, and visionaries pushing the

envelope of what can be achieved on screen.

Some of the last great independent filmmakers, such as Christopher Nolan

and Martin Scorsese, are still directing at a high level. Animated movies such as Spiderman: Across

the Spider-Verse and Puss and Boots: The Last Wish are helping

continue the innovations that Disney and Pixar helped cultivate before their

decline. Independent filmmakers and

studios, notably A24, also have helped maintain the work of master filmmakers

that was so prevalent throughout much of the 20th century. Even the big Hollywood studios occasionally

produce something new and exciting.

While movies have certainly seen better days, quality films are still

being made by quality artists.

The

Future of Movies

People’s

tastes are changing, and with ticket prices constantly increasing, audiences

are way pickier with what they want to see in theaters. People will go to theaters to see highly

anticipated, high-budget films with exceptional special effects and globally

beloved stars on a massive screen.

Advances

in technology like artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and 3-D will

likely change the way movies are made and experienced. Filmmakers will experiment with new ways of

storytelling and immersion, which could lead to more interactive and immersive

movie experiences to make the movie-going experience more fun.

|

| Artificial Intelligence, Virtual Reality, and 3-D offer the potential of immersive, interactive movies. |

Increasingly,

theaters will specialize in event, immersive, and interactive movies, while

studios will prefer a streaming-only release for films that people have no

incentive to leave their house for.

One

exception is likely to be for small, independent theaters whose business model

doesn’t include blockbusters at all. And, there's still a place for

people who want the communal experience, maybe followed by discussion groups or

movie clubs.

Most

mid-budget movies will probably go directly to streaming.

With

streaming available, audiences often will wait (more and more titles are coming

out to rent at home almost as soon as they hit theaters) to watch the film if

the movie doesn't feel like an event or isn’t worth paying $15 to see in a

theater. Theaters and streaming will

just have to co-exist with one another, something that looked unthinkable until

COVID-19 arrived.

For movies in general, studios are at a crossroads, and

they must decide whether to continue to decline with their stagnant

corporatized production of movies, or to take a leap of faith in new ideas and

new artists.

As audiences demand greater diversity and representation in

film, we may see more movies made by and for underrepresented groups. This could lead to a greater variety of

stories being told and a more inclusive film industry overall. And it could lead to a big box office for

those movies.

Streaming

platforms will try to keep their content library as fresh and exciting as

possible to entice new customers to stay.

And they will collect data and insights about viewing behavior,

patterns, and preferences to focus their marketing.

When there are no good sports on TV, I download and watch movies, everything from B-movie westerns from the mid-1940s, to the most recent thrillers.

Sources

My

principal sources for my two-part series on the history of movies in the USA include:

“A Very Short History of Cinema,” sciencenadmediumusum.org; “history of film,”

Britannica.com; “A History of Movies in the USA,” theaterseatstore.com; “The

current state of American cinema,” the spectator.medium.com; “What is the

Future of Cinema?” businessbecause.com; “Domestic Movie Theatrical Market

Summary 1995 to 2024,” the-number.com; plus, numerous other online sources.

Comments

Post a Comment