HISTORY89 - Ten More Historical Myths

Two blogs ago, I wrote about ten historical myths, that though not true, persist in our general discourse today. I received a positive response from that blog, and found ten more myths that I wanted to write about.

After a short introduction, I will discuss these ten additional historical myths in approximate historical order.

My principal sources include:

“The 20 Greatest Historical Myths,” writespirit.net; “Myths Debunked: 5 Widely

Believed Tales about Historical Figures,” blog.gale.com; “7 Things People Ge

Wrong About American History,” time.com; “10 Popular History Myths (You

Probably Believe),” whatculture.com; “Gladiator,” “Date of birth of Jesus,” and

“Albert Einstein,” Wikipedia.com; “Spanish in the U.S.,” pbs.org; “Early

English Settlements,” joliet86.org; “A brief history of tobacco,"

edition.cnn.com; “Potato Fun Facts & History,” bsffl.com; “Continental

Congress adopts the Declaration of Independence,” history.com; “Constitutional

Republic,” legaldictionary.net; “Five myths about slavery,” washingtonpost.com;

“Slaves in New England,” medfordhisotrical.org; “The Halloween myth of the War

of the Worlds panic,” bbc.com; “women’s rights movement,” Britannica.com; plus,

numerous other online sources.

Myth: Roman gladiators were slaves.

A gladiator was an armed

combatant who entertained audiences in the Roman

Republic and Roman Empire in violent confrontations with other

gladiators, wild animals, and condemned criminals.

There's a nearly-universal false

notion (probably promulgated in movies) about what it meant to be a Roman

gladiator. First and foremost, a

gladiator was a slave. He was forced to

become a gladiator, fighting in brutal matches for aristocratic Roman

spectators, and those wealthy aristocrats gave the final thumbs-up or

thumbs-down to determine whether he lived or died.

Yes, some gladiators were slaves. But many gladiators were free citizens -

aristocrats, even - who voluntarily signed up to fight. Gladiator matches were a spectator sport, and

if the gladiator were successful, there was incredible wealth, fame, and glory

to be had in the ring. Gladiators

were celebrated as entertainers and commemorated in precious and commonplace

objects throughout the Roman world.

It wasn’t easy for gladiators to stand

out. Each warrior fought only two to

three times per year, usually in events featuring 10 to 13 gladiator fights - with

each individual match lasting about 10 to 15 minutes. But some, owing to their extravagant

personalities, personal backgrounds, or memorable performances, gained lasting

renown.

Contrary to popular perception,

gladiators didn’t necessarily battle to the death. Instead, fighting progressed until one of them

surrendered, usually by holding up a single finger. Only between 10 and 20 percent of

gladiators died during matches - a reflection, in part, of their high financial

value to investors.

Note: Investors

were usually the owner or business manager of a school for gladiators. New gladiators “went to school,” were fed a

good diet, had medical care, and received several months of training.

Their sponsors made gladiators pack on

weight so that they could sustain shallow, non-lethal cuts in their

subcutaneous fat. The crowds liked blood, and they were going to give it to

them!

Many gladiators were free citizens who voluntarily signed up to fight.

The origin of gladiatorial combat is

open to debate. There is evidence of it

in funeral rites during the Punic Wars of the 3rd century

BC, and thereafter it rapidly became an essential feature of politics and

social life in the Roman world. Its

popularity led to its use in ever more lavish and costly games.

The gladiator games lasted for over

650 years, reaching their peak between the 1st century BC and the 2nd

century AD. Christians disapproved of

the games because they involved idolatrous pagan rituals. The popularity of gladiatorial contests waned

and disappeared in the 5th century, with the decline of the Roman

Empire.

Myth: Jesus was born on December 25th.

Even if you're not a Christian, the

sheer number of Christians in the world (2.38 billion in 2020) - coupled with

the widespread commercialization of the Christmas holiday - pretty much

guarantees that most people "know" that Christmas is Jesus'

birthday. Yes, Christmas is meant to

celebrate the birth of Jesus, but there is no evidence

whatsoever, biblical, or otherwise, that He was actually born on December 25th.

There is no evidence that Jesus was born on December 25th.

Christ wasn't initially tied to

Christmas, at all. Early Christians said

nothing of Jesus's birthdate. The

earliest reference to his date of birth scholars have found dates to AD 336,

when the church of Rome put on a nativity festival. Supposedly, in AD 350, Pope Julius I asserted

officially that Jesus’s birthdate was December 25th, but this claim

has not been proven.

Historians disagree on how December 25

became associated with Christmas. The

most reasonable explanations (at least to me) relate to festivals and

celebrations already occurring in mid to late December in the Roman world.

Consider that the middle of winter has

long been a time of celebration around the world. Centuries before the arrival of the man

called Jesus, many people rejoiced during the winter solstice, when the

worst of the winter was behind them, and they could look forward to longer days

and extended hours of sunlight. Prior to and through the early

Christian centuries, winter solstice festivals were the most

popular of the year, in many European pagan (polytheistic) cultures.

Note: The winter solstice is the shortest day and

longest night of the year. In the

Northern Hemisphere, it takes place between December 20 and 23, depending on

the year.

In Rome, where winters were not as

harsh as those in the far north, Saturnalia - a holiday in honor of Saturn, the

god of agriculture - was celebrated.

Beginning in the week leading up to the winter solstice and continuing

for a full month, Saturnalia was a hedonistic time, when food and

drink were plentiful and the normal Roman social order was turned upside

down. For a month, enslaved people were

given temporary freedom and treated as equals.

Business and schools were closed so that everyone could participate in

the holiday's festivities.

Also, consider that in the

early years of Christianity, Easter was the main holiday; the birth of

Jesus was not celebrated. In particular, during the first two

centuries of Christianity, there was strong opposition to recognizing

birthdays of martyrs, including Jesus.

Numerous Church Fathers offered sarcastic comments about the pagan

custom of celebrating birthdays, when, in fact, saints and martyrs should be

honored on the days of their martyrdom - their true “birthdays,” from the Church’s

perspective.

All of that changed in the fourth

century when the Church officially adopted December 25 as the

official date when Christians would celebrate the birth of Jesus. Why the change? The reasons are still debated (the Bible

provides no clue), but a generally accepted belief is that December 25 was

chosen to adopt and absorb the traditions of Rome’s popular existing pagan Saturnalia festival, and

other pagan festivals around the world that were celebrated at the time of

the winter solstice.

Today, Christmas is celebrated annually on December 25,

having evolved as both a sacred religious holiday and a worldwide cultural and

commercial phenomenon.

See my blog on the history of Christmas at https://bobringreflections.blogspot.com/2022/11/history66-christmas.html.

Myth: England had permanent settlements in

continental America before Spain.

This misconception probably

persists because the first English settlements in America opened the door for

subsequent European settlement along the east coast of present-day America, and

expanded inland to form settlements that eventually became the original 13

colonies (states) of the United States of America.

But the Spanish

established the first permanent settlement in America 42 years before the

English.

Led by Ponce de León, the

Spanish first arrived in 1513 in the present-day continental United States on

the Florida peninsula and returned in 1520 for further exploration. By 1565, they had established their first

permanent colony, Saint Augustine, Florida, under the leadership of Pedro

Menéndez de Avilés. Between 1520 and

1570, the Spanish vigorously explored the Atlantic coast, with specific

explorations taking place in the Carolinas, Virginia, Georgia, and along the

New England coast.

Artist rendering of Saint Augustine in 1671.

The earliest Spanish

explorations of the present southwestern U.S. date to 1540 by Francisco

Coronado. Juan de Oñate followed in 1598, establishing the first

permanent European settlement in New Mexico at San Juan Pueblo. Santa Fe was founded in 1610.

In addition to the Spanish, other

European nations had explored the northern east coast of future America,

starting in 1497 with Italian John Cabot.

Almost a century later, it was the English who sought to make settlements

there.

In 1585, Roanoke, an island off the

coast of North Carolina, became the first English settlement. But no one knows what happened to its

settlers. No signs of them remained when

resupply ships from England came to find them later. That is why, today, Roanoke is called the

“lost colony.”

More than 20 years after the attempt

to settle Roanoke, 105 Englishmen arrived in present-day Virginia seeking gold

and other riches. They founded a settlement called Jamestown in 1607. Despite many hardships, Jamestown became the

first successful English colony in North America.

A few years later in 1620, a group of

102 English people arrived in present-day New England. They built a settlement called Plymouth, in

what is now the state of Massachusetts.

Most of these people had left England to seek religious freedom. They became known as the Pilgrims, people who

go on a religious journey.

Myth: Sir Walter

Raleigh introduced tobacco and the potato to Europe.

Sir Walter

Raleigh (1552-1618) was an English adventurer, writer, and nobleman. After growing close to Queen Elizabeth I

during his time in the army, Raleigh was knighted in 1585, and became captain

of the guard.

During Elizabeth’s reign, Raleigh organized three major

expeditions to America: 1) 1584 - exploration

of North America from North Carolina to

present-day Florida; the region was named Virginia in honor

of Elizabeth; 2) 1585 and 3) 1587 - sent expeditions of colonists

to Roanoke (which as noted above disappeared mysteriously). Raleigh himself never visited North America, although he led

unsuccessful expeditions in 1595 and 1617 to the Orinoco River basin

in South America in search of the golden city of El Dorado.

Tobacco and the potato were introduced

to Europe well before Sir Walter Raleigh had anything to do with the Americas.

Tobacco was first used by the peoples

of the pre-Columbian Americas, who apparently cultivated the plant and smoked

it in pipes for medicinal and ceremonial purposes. Christopher Columbus brought a few tobacco

leaves and seeds with him back to Europe, but most Europeans didn't get their

first taste of tobacco until the mid-16th century, when adventurers

and diplomats like France's Jean Nicot - for whom nicotine is named - began to

popularize its use.

Pictures like this promulgate the myth that Sir Walter Raleigh introduced tobacco to Europe.

The first successful commercial

tobacco crop in America was cultivated in Virginia in 1612 by Englishman John

Rolfe. Within seven years, it was the

colony's largest export. Over the next

two centuries, the growth of tobacco as a cash crop fueled the demand in North

America for slave labor.

In 1536, Spanish Conquistadors in Peru discovered the flavors

of the potato and transported potatoes to Europe. At first, the vegetable was not widely

accepted. Towards the end of the 16th

century, families of Basque sailors began to cultivate potatoes along the

Biscay coast of northern Spain. It took

nearly four decades for the potato to spread to the rest of Europe. Eventually, agriculturalists in Europe found

potatoes easier to grow and cultivate than other staple crops, such as wheat

and oats. Most importantly, it became known that potatoes contained most

of the vitamins needed for sustenance.

Potatoes arrived in England’s New World colonies in the 1621

when the Governor of the Bahamas sent a gift box containing potatoes to the

governor of the colony of Virginia.

The first permanent potato patches in North America were

established in 1719, most likely near Londonderry (Derry), New Hampshire, by

Scotch-Irish immigrants. From there, the crop spread across the

country.

Myth: America

became independent from England on July 4, 1776.

America’s founding fathers signed the Declaration of

Independence on July 4, 1776. But declaring independence was not the same thing

as being independent.

Following the end of the Revolutionary War, in September 1783, the U.S. signed

a peace treaty with Britain, and the United States formally became an

independent nation.

Let’s review the major events leading

to true independence:

After the British gained victory over the French in

the Seven Years' War in 1763, tensions and disputes arose between

Britain and their American colonies over the lack of political representation

in the homeland and policies related to trade, trans-Appalachian settlement,

and taxation. In mid-1774, Britain

closed Boston Harbor, and revoked Massachusetts' charter, which

placed the colony under the British monarchy's direct governance. All of these issues strengthened American

Patriots' desire for independence from Britain.

On April 19, 1775 the first shots of the

Revolutionary War were fired at Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts. The

news of the bloodshed rocketed along the eastern seaboard, and thousands of

volunteers converged - called "Minute Men" - in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The Continental Army was formed on June 14, 1775 by a

resolution of the Second Continental Congress, meeting

in Philadelphia after the war's outbreak. The Continental Army was created to coordinate

military efforts of the colonies in the war against the British, who

sought to maintain control over the American colonies. General George Washington was

appointed commander-in-chief of the Continental Army and maintained this

position throughout the war.

In January 1776, Thomas

Paine published “Common Sense,” an influential political pamphlet that

convincingly argued for American independence. In the spring of 1776, support for

independence swept the colonies, the Continental Congress called for colonies

to form their own governments, and a five-man committee was assigned to draft a

declaration.

On July 2, 1776, the Continental

Congress voted to approve a Virginia motion calling for separation

from Britain. Two days later,

on July 4, the Declaration of Independence was formally adopted.

But the Revolutionary

War would last for five more years. Yet to come were the Patriot triumphs at

Saratoga, the bitter winter at Valley Forge, the surprise attack across the

Delaware River on Trenton, the intervention of the French, and the final

victory at Yorktown in 1781. On September 3, 1783, with the signing of the Treaty

of Paris with Britain, the United States formally became a free and independent

nation.

Emanuel Leutze’s famous painting of Washington crossing the Delaware for a surprise attack on Trenton - a key Revolutionary War event in the march to true independence.

Myth: The U.S. is

a democracy.

The truth

is the United States is a Constitutional Republic, not a democracy.

Paraphrasing

from the online Legal Dictionary: A

constitutional republic is a form of government in which the head of the state,

as well as other officials, are elected by the country’s citizens to represent

them. Those representatives must then follow the rules of that country’s

constitution in governing their people. Like the U.S. government, a constitutional

republic may consist of three branches - executive, judicial, and legislative -

which divide the power of the government so that no one branch becomes too

powerful.

A country

is considered a constitutional republic if:

·

It has a

constitution that limits the government’s power

·

The

citizens choose their own heads of state and other governmental officials

Many

people believe that the United States is a democracy, but it is

actually the perfect example of a constitutional republic. A pure democracy would be a form of government

in which the leaders, while elected by the people, are not constrained by a

constitution as to its actions.

The Founding Fathers thought change

should occur slowly, as many were afraid that a "democracy" - by

which they meant a direct democracy – would allow a majority of

voters at any time to trample rights and liberties. They thought

democracy could take the form of mob rule that could be shaped on the

spot by a demagogue. Therefore, they

devised a written Constitution that could be amended only by a super majority.

We do not

have pure democracy or “rule by the majority” because we have constitutionally

protected rights that cannot be voted away, operate under rule of law, and have

limited government with limited powers.

Our

founding was saved by the skill of our “political pilots” to craft a compromise

between popular will and the rule of law.

We are democratic, but we are not a democracy. We the People are those whose consent

is required, but the Constitution is the Supreme Law of the Land.

The Pledge of Allegiance, which was written in 1892 and adopted by Congress in 1942 as the official pledge, refers to the U.S. as a republic.

Myth: Slavery was

confined to the South.

Not true. Enslaved people were brought into New England

throughout the entire colonial period, and slavery existed throughout the

colonies before the American Revolution.

Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island were the three New England

states with the largest slave population.

Slaves accounted for as much as 30 % of the population in South

Kingston, Rhode Island, and were a significant presence in Boston (10%), New

London (9%), and New York (7.2%).

Slavery was integral to the building of New York

City and Newport and Providence, Rhode Island.

As the United States expanded westward

after the Revolutionary War, virtually every new state - south and north -

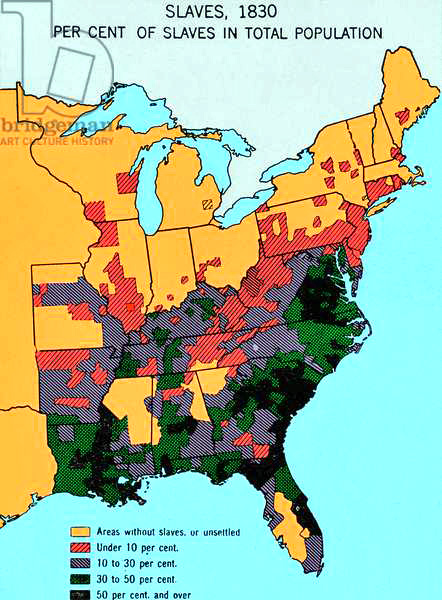

practiced slavery to a degree. See the

figure below.

Virtually every U.S. state practiced slavery in 1830.

For nearly two hundred years the North maintained a slave regime

that was more varied than that of the South.

Rather than using slaves as primarily agricultural labor, the

North trained and diversified its slave force to meet the needs of its more

complex economy. Owned mostly by

ministers, doctors, and the merchant elite, enslaved men and women in the North

often performed household duties in addition to skilled jobs.

From the 17th century onward, slaves in the North could

be found in almost every field of Northern economic life. They worked as carpenters, ship builders,

sailmakers, printers, tailors, shoemakers, coopers, blacksmiths, bakers,

weavers, and goldsmiths.

Slavery in

the North lasted well into the 1840s.

Myth: Einstein was

a lousy student who failed math in school.

Albert Einstein (1879 -1955) was a

German-born theoretical physicist who is widely held to be one of the

greatest and most influential scientists of all time. Best known for developing the theory of

relativity, Einstein also made important contributions to quantum

mechanics, and was thus a central figure in the revolutionary reshaping of the

scientific understanding of nature that modern physics accomplished

in the first decades of the 20th century. He received the 1921 Nobel Prize in

Physics "for his services to theoretical physics, and especially for

his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect,” a pivotal step

in the development of quantum theory. In

a 1999, poll of 130 leading physicists worldwide by the British journal Physics

World, Einstein was ranked the greatest physicist of all time. His intellectual achievements and originality

have made the word Einstein broadly synonymous with genius.

Where the myth that Einstein failed

math in school came from is unknown. The

truth is that Einstein's math scores in school were even better than his

science scores. He wasn't a fan of

school early on, but that hardly equates to him being bad at it. He did fail an entrance exam for Zurich

Polytechnic Institute, but only because it was in French, and he wasn’t fluent

in French. He did outstanding on the

math section, but failed the language, botany, and

zoology section.

Theoretical physicist Albert Einstein excelled at math and physics at an early age.

In fact, Einstein excelled at physics and mathematics from an

early age. By age 11,

he was reading college-level physics textbooks. He began teaching himself algebra, calculus,

and Euclidean geometry when he was 12; he made such rapid progress

that he discovered an original proof of the Pythagorean theorem before

his thirteenth birthday. A family

tutor, Max Talmud, said that only a short time after he had given the

twelve-year-old Einstein a geometry textbook, the boy "had worked through

the whole book. He thereupon devoted

himself to higher mathematics ... Soon the flight of his mathematical

genius was so high I could not follow.”

Einstein recorded that he had “mastered integral and differential

calculus" while still just 14. His

love of algebra and geometry was so great that at 12, he was already confident

that nature could be understood as a "mathematical structure.”

Myth: Mass panic and hysteria swept the United

States on the eve of Halloween in 1938, when an all-too-realistic radio

dramatization of The War of the Worlds sent untold thousands of people

into the streets or heading for the hills.

The radio show was so

terrifying in its accounts of invading Martians wielding deadly heat-rays that

it is remembered like no other radio program.

Or, more accurately, it is misremembered like no other radio program. Yes, some Americans were frightened or

disturbed by what they heard. But most

listeners, overwhelmingly, were not. They recognized it for what it was - a clever

and entertaining radio play.

The War of the Worlds

dramatization was the inspiration of Orson Welles, director and star of the

Mercury Theatre on the Air, an hour-long program that aired on Sunday evenings

on CBS Radio. Welles was 23 years old, a

prodigy destined for lasting fame as director and star of the 1941 motion

picture, Citizen Kane. His

adaptation of The War of the Worlds, a science fiction thriller written

by HG Wells and published in 1898, was little short of brilliant.

What made the show so

compelling was the use of simulated on-the-scene radio reports telling of the

first landing of Martian invaders near Princeton, New Jersey, and their swift

and deadly advance to New York City. American

audiences had become accustomed to news reports interrupting radio programs. They had heard them often during the war scare

in Europe in late summer and early autumn of 1938. Welles played on this familiarity to stunning

effect. In doing so, he created a

delicious and tenacious media myth.

It is estimated that six

million people listened to The War of the Worlds dramatization. Most listeners, by far, were not upset by the

show.

Reading of

contemporaneous newspaper reports reveals the fright that night was highly

exaggerated. Newspapers presented

sweeping claims about thousands or even millions of panic-stricken Americans,

but offered little supporting documentation.

Newspaper headlines

across America told of the terror that Welles' show supposedly created:

·

"Radio Listeners in Panic,

Taking War Drama as Fact," declared the New York Times.

·

"Radio Fake Scares

Nation," cried the Chicago Herald and Examiner. "US Terrorized

By Radio's 'Men From Mars,'" said the San Francisco Chronicle.

Newspapers greatly exaggerated the effect of Orson Welles’ radio dramatization of War of the Worlds.

Despite its wobbly

basis, the myth of mass panic remains steadfastly attached to The War of the

Worlds program. It is part of the

lore of Orson Welles, the bad-boy genius who did his best work before he turned

30.

Myth: The Woman’s Liberation movement was hostile

to men.

No social movement, arguably, has been

so misrepresented as the 1960s -1970s women’s rights movement. In these myths, feminists were single, middle

class, and white; mainly concerned with “sex issues,” such as pornography,

abortion rights, sexual harassment, and rape; and hostile to men. Each is wrong.

The feminism of that period was

diverse in class and race from its beginnings.

Working-class, labor-union women - black, white, and Latina - were

leaders in the 1960s revival of feminism.

Feminists did focus campaigns on sex issues but they often prioritized

economic goals: better pay, especially in low-wage women’s jobs; equal access

to higher-salary jobs, and traditionally male jobs; and medical care and sick

leave.

With the leadership of Journalist Betty Friedan and writer and social activist Gloria Steinem, women

called for honoring and valuing women’s unpaid family labor. Experiencing the stress of combining unpaid

and paid work, feminists campaigned for policies aimed to reducing that stress,

such as paid parental leave, flexible schedules, and quality, affordable child

care.

The Women’s Liberation movement was not hostile to men.

The women’s rights movement achieved much in a short period

of time. With the eventual backing of

the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (1965), women gained

access to jobs in every corner of the U.S. economy, and employers with long

histories of discrimination were required to provide timetables for

increasing the number of women in their workforces. Divorce laws

were liberalized; employers were barred from firing pregnant women; and women’s

studies programs were created in colleges and universities. Record numbers of women ran for - and started

winning - political office. In 1972

Congress passed Title IX of the Higher Education Act, which

prohibited discrimination on the basis of sex in any educational program

receiving federal funds and thereby forced all-male schools to open their doors

to women and athletic programs to sponsor and finance female sports teams. And

in 1973, in its controversial ruling on Roe v. Wade,

the United States Supreme Court legalized abortion.

In 2016, 60% of American women and 30%

of men called themselves feminists or strong feminists. Far from man-hating, feminists were confident

that men could change, and that they would benefit from feminist policies, and

they were right.

History is a set of lies, agreed upon.

Napoleon Bonaparte

Comments

Post a Comment