HISTORY81 - Michelangelo

My last three blog articles have been about Leonardo da Vinci, the supremely gifted Italian, who was active during the Renaissance as a painter, scientist, and inventor - considered one of the greatest painters in the history of art. This article is about the younger contemporary of Da Vinci, Michelangelo - an equally talented and renowned artist of the Renaissance.

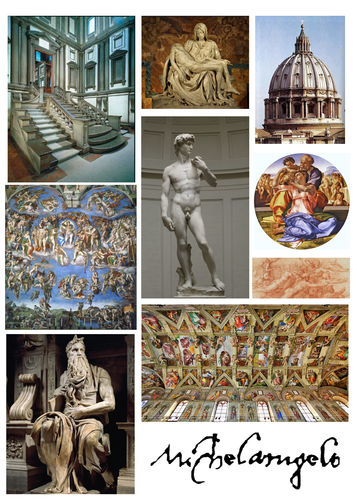

Collage of some of Michelangelo’s best work. The Sistine Chapel ceiling fresco is at lower right. The statue of David is at the center, and the Pieta statue is at the upper center.

I will start with a short introduction, then talk about

Michelangelo’s birth and childhood, his training and apprenticeship, followed

by a discussion of Michelangelo’s artistic life and accomplishments. I will end with some conclusions, including

some thoughts on Michelangelo’s legacy.

My principal sources include “Michelangelo,” Wikipedia.com; “Michelangelo - Italian

Painter, Sculptor, Poet, and Architect,” theartstory.org; “Michelangelo -

Italian Artist,” britannica.com; “Michelangelo,” biography.com; “Michelangelo’s

10 most popular works - ranked,” news.artnet.com; “10 Most Famous Works by

Michelangelo,” leonardo-newton.com/michelangelo-famous-works; “The Da Vinci

feud: Great artistic rivalry with Michelangelo remembered ahead of new

exhibition,” sundaypost.com; plus, numerous other online sources.

Introduction

Michelangelo, in

full Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (1475 - 1564), was an

Italian Renaissance sculptor, painter, architect, and poet

who exerted an unparalleled influence on the development of Western

art. It is universally accepted that

Michelangelo was one of the greatest artists in the history of art.

He conjured figures, both carved and

painted, that were infused with such psychological intensity and emotional

realism they set a new standard of excellence. Michelangelo's most seminal pieces: the

massive painting of the biblical narratives on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, the

17-foot-tall and anatomically flawless statue of David, and the heartbreakingly

genuine Pietà statue, are considered some of the greatest achievements in human

history.

In his lifetime, Michelangelo was

often called "the divine one." His contemporaries admired his ability to

instill a sense of awe in viewers of his art.

Michelangelo's creative abilities and

mastery in a range of artistic arenas define him as the ultimate Renaissance

man, along with his rival and elder contemporary, Leonardo da Vinci.

Birth and Childhood: 1475 - 1488

Michelangelo was born on March 6, 1475

in Caprese, known today as Caprese Michelangelo, a small town situated in

Valtiberina, near Arezzo, Tuscany, Italy. He was born to Leonardo di Buonarrota and

Francesca di Neri del Miniato di Siena, a middle-class family of Florence

bankers. At the time of Michelangelo’s birth his

father had taken a temporary job as administrator of the small town of

Caprese. A few months later, however,

the family returned to its permanent residence in Florence.

Michelangelo’s mother's unfortunate

and prolonged illness, which led to her death while Michelangelo was just six

years old, forced his father to place his son in the primary care of his

nanny. The nanny was married to a

stonecutter, and legend tells it that this domestic situation would form the

foundation for the artist's lifelong love affair with marble.

Michelangelo was less interested in

schooling than watching the painters at nearby churches, and then drawing what

he saw.

Training and Apprenticeship:

1488 - 1492

In the late 15th century,

the city of Florence was Italy's greatest center of the arts and learning. During Michelangelo's childhood, a team of

painters had been called from Florence to the Vatican to decorate the walls of

the Sistine Chapel. Among them

was Domenico Ghirlandaio, a master in fresco painting, perspective, figure

drawing, and portraiture who had the largest workshop in Florence.

Michelangelo's father realized early

on that his son had no interest in the family financial business, so in 1488 he

agreed to apprentice him, at the age of 13, to Ghirlandaio. There, Michelangelo

was exposed to the technique of fresco (where pigment is placed directly on

fresh, or wet, lime plaster), and received a thorough grounding in

draftsmanship.

After only a year in the studio,

Ghirlandaio recommended Michelangelo to Lorenzo de' Medici, the ruler of

Florence, and renowned patron of the arts.

From 1489 to 1492, Michelangelo studied classical

sculpture in the Medici palace gardens.

This was a fertile time for

Michelangelo; his years with the Medici family permitted him access to the

social elite of Florence - allowing him to study under the respected sculptor

Bertoldo di Giovanni, and exposing him to prominent poets, scholars, and

learned humanists.

He also obtained special permission

from the Catholic Church to study cadavers for insight into anatomy. He dissected bodies and drew from models,

till the human figure did not hold any secrets for him. However, unlike Leonardo da Vinci, for whom

human anatomy was just one of the many "riddles of nature,” Michelangelo

strove with an incredible singleness of purpose to master this one problem, but

to master it fully.

Michelangelo's uncanny ability to

render the muscular tone of the body was evidenced in his two surviving relief

sculptures from the period: Madonna of the Stairs (1491),

and Battle of the Centaurs (1492) - testaments to his

phenomenal talent at the tender age of 16.

Michelangelo's earliest known work in marble, Madonna on the Stairs (1491).

Early Years: 1492 - 1505

In 1494, as the Republic of Florence

was under the threat of siege from the French, Michelangelo, fearing for his

safety, moved from Florence to the relative safety of Bologna. He was befriended by the wealthy Bolognese

senator, Giovan Francesco Aldrovandi, who was able to secure the 19-year-old

Michelangelo the commission to complete the remaining statuettes for the marble

sarcophagus lid for the Shrine of St. Dominic.

Michelangelo sculpted the few remaining figures, including Saint

Proculus, Saint Petronio, and the Angel with Candelabra, in

1494 - 1496.

Michelangelo returned briefly to

Florence after the threat of the French invasion abated. He worked on two statues, one of St.

John the Baptist, the other, a small cupid that was sold to Cardinal Riario

of San Giorgio. Cardinal Riario was

impressed by Michelangelo's skill and invited him to Rome to work on a new

project. Michelangelo arrived in Rome

in June 1496 at the age of 21.

Michelangelo’s first surviving large

statue, the Bacchus (1497), the Roman god of wine, was produced in

Rome. The Bacchus relies

on ancient Roman nude figures as a point of departure, but it was much more

mobile and more complex in outline. The

conscious instability (tipsy?) of the party-loving god of wine was unprecedented

realism at the time. Sitting behind Bacchus was a faun, who eats the bunch of

grapes slipping out of Bacchus’s left hand. Made for a garden, it is also unique

among Michelangelo’s works in calling for observation from all sides, rather

than primarily from the front.

Michelangelo’s first surviving large sculpture, Bacchus (1497).

The Bacchus led at

once to the commission for the Pietà (1499) now in St.

Peter’s Basilica. Extracted from

narrative scenes of the lamentation after Christ’s death, the

concentrated group of two is designed to evoke the observer’s repentant prayers

for sins that required Christ’s sacrificial death. The complex problem for the designer was to

extract two figures from one marble block.

Michelangelo treated the group as one dense and compact mass so that it

has an imposing impact, yet he underlined the many contrasts present - of male

and female, vertical and horizontal, clothed and naked, dead and alive. It was soon to be

regarded as one of the world's great masterpieces of sculpture.

Michelangelo’s Pieta (1499), one of the world’s great masterpieces of sculpture.

Michelangelo’s prominence, established

by this work, was reinforced at once by the commission of the David (1504),

a 17-foot-tall nude statue, for the Cathedral of Florence. Michelangelo reused a marble block left

unfinished about 40 years before. The

statue of David has continued to serve as the prime statement of the

Renaissance ideal of perfect humanity and is his most famous work. It was drawn from the well-known Biblical story of a young boy fighting the giant Goliath. But

while others chose to emphasize his smallness, Michelangelo’s David is

a giant himself: A muscular,

confident man prepared for battle. The masterwork definitively established Michelangelo’s

preeminence as a sculptor of extraordinary technical skill and strength of

symbolic imagination.

The statue of David (1504) is Michelangelo’s most famous work.

The magnificence of the finished work convinced Michelangelo’s contemporaries to install it in a prominent place, to be determined by a commission formed of artists and prominent citizens. They decided that the David would be installed in front of the entrance of the Palazzo dei Priori (now called Palazzo Vecchio) as a symbol of the Florentine Republic. It was later replaced by a copy, and the original was moved to the Galleria dell" Accademia.

On the side, Michelangelo produced in

the same years (1501-04) several Madonnas for private houses,

the staple of artists’ work at the time. These include one small statue, two circular

reliefs that are similar to paintings in suggesting varied levels of spatial

depth, and the artist’s only easel painting.

One of the Madonna sculptures, the Madonna of Bruges (1504),

depicted a somewhat detached Mary, who looks away as if she knows her son’s

future, while the infant Jesus is mostly unsupported and appears to be stepping

away from her mother and into the world.

This sculpture is often included in Michelangelo’s ten greatest works.

The Madonna of Bruges (1504) is often included in the top 10 works by Michelangelo.

Also, during this period, Michelangelo

was commissioned by wealthy merchant by Angelo Doni to paint a "Holy

Family" as a present for his wife, Maddalena Strozzi. Michelangelo used the form of a tondo, or round frame, for

the painting. Doni Tondo (1504)

features the Christian Holy family (the child Jesus, Mary, and Saint

Joseph) along with John the Baptist in the foreground, and contains five

ambiguous nude male figures in the background. It is the only finished panel painting by the

mature Michelangelo to survive.

Doni Tondo (1504) is the only of Michelangelo’s finished panel paintings to survive.

Middle Years: 1505 - 1541

In 1505, still in Florence,

Michelangelo began work on a Medici project for 12 marble Apostles for the

Florence Cathedral, of which only one, the St. Matthew, was even

begun.

That was because Pope Julius II’s

call to Michelangelo to come to Rome spelled an end to that

Florentine project. The pope wanted a

tomb for which Michelangelo was to carve 40 large statues. Pope Julius had an ambitious imagination,

parallel to Michelangelo’s, but because of the Pope’s other projects, such as

the new building of St. Peter’s and his military campaigns, he

evidently became disturbed soon by the cost.

So, instead, Michelangelo was put to

work on the painting of the ceiling of the Sistine

Chapel (1508-12). The Sistine

Chapel had great symbolic meaning for the papacy as the

principal consecrated space in the Vatican, used for great ceremonies

such as electing and inaugurating new popes.

Michelangelo was originally

commissioned to paint the Twelve Apostles on the triangular supports

of the ceiling, and to cover the central part of the ceiling with ornament. But Michelangelo

persuaded Pope Julius II to give him a free hand and proposed a different and

more complex scheme, representing the Creation, the Fall of Man, the

Promise of Salvation through the prophets, and the genealogy of Christ.

Michelangelo worked on the Sistine

Chapel ceiling for nearly four years. It

was a job of extraordinary endurance in which (according to popular mythology)

the artist painted the ceiling lying on his back atop a wooden scaffold

structure (a task made even more difficult given that the tempestuous artist

had dismissed all of his assistants, save one who helped him mix paint). What resulted, however, was a monumental work

of stunning virtuosity. The finished work would become a towering masterpiece

of human creation.

The composition stretched over 5,300

square feet of ceiling and

contained over 300 figures. At its center were nine episodes from

the Book of Genesis, divided into three groups: God's creation of the

earth; God's creation of humankind and their fall from God's grace; and lastly,

the state of humanity as represented by Noah and his family. On the triangular structures supporting the

ceiling were painted 12 men and women who prophesied the coming of Jesus,

seven prophets of Israel, and five Sibyls, prophetic women of

the Classical World.

Fresco paintings on the Sistine Chapel ceiling and altar wall are highlighted in this photograph.

Among the most famous paintings on the

ceiling was The Creation of Adam. The image of the

near-touching hands of God and Adam has become iconic of humanity, and has been

imitated and parodied innumerable times.

The center panels of Michelangelo’s painting of the ceiling in the Sistine Chapel. The Creation of Adam scene is at upper center.

With his decoration of the Sistine

Chapel ceiling complete, Michelangelo resumed work on Julius II’s tomb. Between 1512 and 1513, he completed three

sculptures for the project, including Moses. The Moses sculpture exhibited richer

surface detail and modeling than in his earlier sculptures, with bulging

projections sharply formed, the artist by now having found how to enrich detail

without sacrificing massiveness.

.jpg)

The center panels of Michelangelo’s painting of the ceiling in the Sistine Chapel. The Creation of Adam scene is at upper center.

Julius II died in

February 1513. A new contract was drawn

up with Julius’s heirs which specified completion of the project as a wall

tomb.

Note: Through the 1520s,

1530s, and 1540s, Michelangelo continued to work on the tomb as time and

funding permitted. Finally, in 1545, 40

years after starting, the tomb, more properly called a funerary monument

because Julius II was not interred there, was completed on a much-reduced scale,

and installed in the Church of San Pietro in Rome.

Meanwhile, Pope Leo X, Julius

II’s successor, a son of Lorenzo the Magnificent, had known Michelangelo

since their boyhoods. He chiefly

employed Michelangelo in Florence on projects linked to the glory

of the Medici family rather than of the papacy. The city was under the rule of Leo’s cousin,

Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici, who was to be Pope Clement VII from 1523

to 1534, and Michelangelo worked closely with both popes.

Michelangelo worked on a design for the

Medici Chapel, to be an annex to the Florence Cathedral. Up to 1527, his chief

attention was to the marble interior of this chapel, both the very original

wall design and the carved figures on the tombs. He started on several sculptures, but the

only ones actually completed were the statues of the Dukes Lorenzo and

Giuliano, the allegories of Dawn and Dusk, Night and Day, and

the group of Madonna and Child.

These figures are among Michelangelo’s most famous and accomplished

creations.

During the same years, Michelangelo

designed another annex to the Florence Cathedral, the Laurentian Library. The entrance lobby and staircase walls

contain Michelangelo’s most famous and original wall designs.

Note: Construction of the library began in 1524. But there were various interruptions and the

library didn’t open until 1571, seven years after Michelangelo’s death. At the time, it was a resounding

architectural triumph and considered a masterpiece.)

The sack of Rome in 1527 saw

Pope Clement ignominiously in flight, and Florence revolted against the Medici,

restoring the traditional republic. It

was soon besieged and defeated, and Medici rule permanently reinstalled, in

1530. During the siege Michelangelo was

the designer of fortifications. He

showed understanding of modern defensive structures built quickly of simple

materials in complex profiles that offered minimum vulnerability to attackers

and maximum resistance to cannon and other artillery.

Shortly

before his death in 1534, Pope Clement VII commissioned Michelangelo to paint a

fresco of The Last Judgment on the altar wall of the Sistine

Chapel.

So, in 1534, Michelangelo left

Florence for the last time, though he always hoped to return to finish the

projects he had left incomplete. He

passed the rest of his life in Rome.

Michelangelo

labored on The Last Judgement from 1534 to 1541. The fresco

depicts the Second Coming of Christ and his Judgement of the souls. Michelangelo ignored the usual artistic

conventions in portraying Jesus, showing him as a massive, muscular figure,

youthful, beardless and naked. The dead rise from their graves, to be

consigned either to Heaven or to Hell.

The

painting style was noticeably different from that of the Sistine Chapel

ceiling 25 years earlier. The color

scheme was simpler than that of the ceiling: flesh tones against a stark blue

sky. The figures had less energy and

their forms were less articulate, the torsos tending to be single fleshy

masses without waistlines.

Michelangelo’s The Last Judgement (1541) mural, painted on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel.

Michelangelo’s poetry is

also preserved in quantity from this time.

He apparently began writing short poems in a way common among

nonprofessionals in the period, as an elegant kind of letter, but developed in

a more original and expressive way.

Among some 300 preserved poems, not including fragments of a line or

two, there are about 75 finished sonnets and about 95 finished madrigals,

poems of about the same length as sonnets, but of a looser formal

structure. They give expression to the

theme that love helps human beings in their difficult effort to ascend to the

divine.

Later Years: 1541 - 1564

In his later years, Michelangelo was

less involved with sculpture and, along

with painting and poetry, more with architecture, an area

in which he did not have to do physical labor.

He was sought after to design imposing monuments for the new

and modern Rome that were to enunciate architecturally the city’s

position as a world center. Two of these

monuments, the Capitoline Square and the dome of St.

Peter’s, are still among the city’s most notable visual images. He did not finish either, but after his

death, both were continued in ways that probably did not depart much from his

plans.

Capitoline Hill had been

the civic center in ancient Roman times and was in the 16th

century the center of the lay municipal government, a minor factor in a

city ruled by popes, yet one to which they wished to show respect. Michelangelo's first designs for the public square and

surrounding buildings date from 1536.

Michelangelo remodeled the old city hall on one side of the square and

designed twin buildings for the two sides adjacent to it. He gave them rich and powerful fronts. He also produced a special floor design for

the square between these two new buildings.

Michelangelo’s design of the Capitoline Square in Rome.

Note: Executing the

design was slow. Little was actually

completed in Michelangelo's lifetime, but work continued faithfully to his

designs and the Capitoline Square was finally completed in the 17th

century.

In 1546, Michelangelo was appointed

architect of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. Although

the design by Donato Bramante had been selected in 1505, and foundations laid

the following year, little progress had been made since. By the time Michelangelo reluctantly took over

the project in 1546, he was in his seventies, stating, "I undertake this

only for the love of God and in honor of the Apostle." Michelangelo worked continuously throughout

the rest of his life as Head Architect on the Basilica. His most important personal contribution to

the project was his work on the design of the dome at the eastern point of the

Basilica.

Note:

St. Peter’s Basilica was not completed until 1626, 62 years after

Michelangelo’s death.

Although the dome was not finished

until after his death, the base on which the dome was to be placed was

completed, which meant the final version of the dome remained true in essence

to Michelangelo's majestic vision. Still

the largest church in the world, the dome is both a Roman landmark (rather than

just a functional covering for the building's interior) and a testament to

Michelangelo's eternal connection to the city.

Michelangelo’s design for the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

While remaining head architect of St.

Peter’s until his death, Michelangelo worked on many smaller building projects

in Rome. He completed the main unit of

the Palazzo Farnese, the residence of Pope Paul III’s family. The top story wall of its courtyard is a rare

example of an architectural unit fully finished under his eye.

The poetry of Michelangelo’s last

years also took on new qualities. The

poems, chiefly sonnets, were very direct religious statements, suggesting

prayers.

Michelangelo's last paintings,

produced between 1542-50, were a series of frescos for the private Pauline

Chapel in the Vatican. He continued to

sculpt but did so privately for personal pleasure. He completed a number of Pietàs including

the Deposition (1547 - 1555), as well as his last, the Rondanini

Pietà, on which he worked until the last weeks before his death.

Michelangelo’s final sculpture, the Rondanini Pieta (unfinished).

Michelangelo died in 1564, just before

his 89th birthday, at home in Rome, following a short illness. Per his wishes, his body was returned to his

beloved Florence and interred at the Basilica di Santa

Croce.

Michelangelo’s tomb in the Basilica di Santa Croce in Florence.

Conclusions

Legacy. Michelangelo was the undisputed master

of sculpting the human form, which he did with such technical aplomb that his

marble seemed to almost transform into living flesh and bone. His dexterity with handling human emotions

and psychological insights only enhanced his standing, and brought him

world-wide fame during his own lifetime.

Michelangelo's dexterity to carve an

entire sculpture from a single block of marble remains unmatched.

He complemented his Pietas, David,

and Moses with what is the most famous ceiling fresco in the

world, and has made the Vatican City's Sistine Chapel a site

of pilgrimage for those with and without faith.

It has been said that his dome for Saint Peters, as it rises above the

city of Rome, serves as a fitting monument to the spirit of this singular

artist who his contemporaries called “divine.”

Appreciation of Michelangelo's

artistic mastery has endured for centuries, and his name has become synonymous

with the finest humanist tradition of the Renaissance.

Contemporary Documentation. Michelangelo was the first Western artist whose biography was

published while he was alive. In fact,

three biographies were published during his lifetime. One of them, by Giorgio Vasari, proposed

that Michelangelo's work transcended that of any artist living or dead, and was

"supreme in not one art alone but in all three.”

Michelangelo’s fame also led to the

preservation of countless mementos, including hundreds of letters, sketches,

and poems, more than of any contemporary.

Depression. Though Michelangelo's brilliant mind

and copious talents earned him the regard and patronage of the wealthy, it

created a pervasive dissatisfaction for the reluctant painter, who constantly

strived for perfection but was unable to compromise.

He sometimes fell into spells of

melancholy, which were recorded in many of his literary works: "I am here

in great distress and with great physical strain, and have no friends of any

kind, nor do I want them; and I do not have enough time to eat as much as I

need; my joy and my sorrow/my repose are these discomforts," he once

wrote.

Da Vinci - Michelangelo Rivalry. Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci

were the two giants of the Florentine High Renaissance. Although their names are often cited together,

Michelangelo was younger than Leonardo by 23 years. Because of his reclusive nature, Michelangelo

had little to do with Da Vinci, and outlived him by 45 years.

The following was adapted from the “Da

Vinci feud …,” by Patricia-Ann Young:

We often think of the men as peers but

their relationship was complicated by professional jealousy and differing

approaches to art and life.

Da Vinci’s paintings were rooted in

his love for science and nature, while Michelangelo was more interested in the

perfect beauty of the human body.

To Da Vinci, the artist’s job was to

use that knowledge of nature to make pictures.

For Michelangelo though, art was about the soul, and the way you

expressed the soul was through the human body.

Not through landscape, or drapery, or light and shade. He looked for ideal figures and perfect

beauty all of the time.

The great artists’ personalities were

as different from one another as were their styles. Da Vinci was courtly, amiable, well-dressed

and popular. When he died, he left

behind hundreds of notebooks and papers, but hardly anything at all about his

inner or private life.

Michelangelo was scruffy, rude, and

temperamental, and often fought and argued with his patrons. Yet he left behind numerous poems, letters

and sonnets, full of passion and love for the people he was close to.

Personal Comments and Opinions

1.

Michelangelo

had a unique breadth of successful artistic execution, including sculpture,

painting, architecture, and poetry.

There has never been anyone like him.

2.

Michelangelo’s

principal patrons were high-level people with money, such as popes, influential

cardinals, city leaders, and families of aristocracy. These patrons tended to task Michelangelo

with huge projects, taking years to complete.

Often these projects were cancelled or drastically reduced in scope

because of changes in church, political, or family leadership, patron long-term

funding issues, or wars. I think that

Michelangelo was tainted unfairly with a reputation for not finishing his

projects. He was not a procrastinator

like Leonardo da Vinci.

3.

It

is difficult to assess the comparative brilliance of the artistic works of

Michelangelo and Da Vinci. Michelangelo

completed many more works than Da Vinci.

Taken discipline by discipline, I think that Michelangelo was the much

better and prolific sculptor, equal painter, and the more complete and

influential architect.

4.

On

a 2017 trip to Italy, I stood in awe before (or under) Michelangelo’s Pieta,

David, the ceiling and altar wall of the Sistine Chapel, and the dome of Saint

Peters. I have never had the pleasure of

seeing Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa or the Last Supper.

Comments

Post a Comment