HISTORY78 - Introduction to Leonardo da Vinci

I’ve had Leonardo da Vinci on my

list of potential blog topics for a long time.

But I couldn’t figure out how to approach writing about this fascinating

person. So, with this blog, I decided

just to “jump in,” and see what develops.

This is an overall introduction

to Leonardo the person, his life, and his accomplishments. I may come back later to do more on his

multidiscipline accomplishments. In this

blog, first I’ll provide some historical perspective, then I’ll cover Da

Vinci’s birth and childhood, next I’ll summarize his accomplishments in

historically-ordered periods of his life, and end with a discussion of his

legacy.

My principal sources include: “Renaissance,”

history.com; “Leonardo da Vinci” and “List of Works by Leonardo da Vinci,”

Wikipedia.com; “Leonardo da Vinci - Paintings, Drawings, Quotes, Biography,”

leonardodavinci.net; “Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519),” metmuseum.org;

“Leonardo da Vinci - Italian artist, engineer, and scientist,” britannica.com;

“Leonardo da Vinci Biography in Details,” leonardoda-vinci.org; plus, many

other online sources.

Historical Perspective

Leonardo da Vinci (1452 - 1519) was a supremely gifted

Italian who was active during the Renaissance as a painter, draughtsman,

engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. Da Vinci

lived in a golden age of creativity among such contemporaries as Michelangelo

(1475 - 1564) and Raphael (1483 - 1520).

While

his fame initially rested on his achievements as a painter, Leonardo da Vinci

also became known for his science and engineering ideas. Leonardo is widely regarded to have been

a genius who epitomized the Renaissance.

The Renaissance was a fervent period of European cultural,

artistic, political, and economic “rebirth” following the Middle Ages. Generally described as taking place from the

14th century to the 17th century, the Renaissance

promoted the rediscovery of classical philosophy, literature, and art. Some of the greatest thinkers, authors,

statesmen, scientists, and artists in human history thrived during this era,

while global exploration opened up new lands and cultures to European commerce.

The Renaissance is credited with

bridging the gap between the Middle Ages and modern-day civilization.

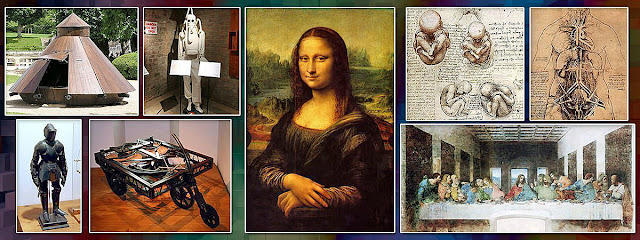

Leonardo da Vinci is one of the greatest painters in the history of art. Despite having many lost works and fewer than 25 attributed major works - including numerous unfinished works - he created some of the most influential paintings in Western art. His magnum opus, the Mona Lisa, is his best-known work and often regarded as the world's most famous painting. The Last Supper is the most reproduced religious painting of all time, and his Vitruvian Man drawing is regarded as a cultural icon of Western civilization.

Three of Leonardo da Vinci’s most influential artworks: painting of The Last Supper (top), painting of Mona Lisa (lower left), and drawing the Vitruvian Man (lower right).

Also revered for

his technological ingenuity, Da Vinci conceptualized flying machines

(including airplanes, helicopters, and parachutes); machines of war (including

battle tanks, machine guns, and cannons); concentrated solar power; a ratio

machine that could be used in an adding machine; and the double hull.

Relatively few of his designs were

constructed or were even feasible during his lifetime, as the modern scientific

approaches to metallurgy and engineering were only in their infancy during

the Renaissance.

Collage of some of Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings and notes of his conceptual inventions.

Some of his smaller inventions,

however, entered the world of manufacturing unheralded, such as an automated

bobbin winder and a machine for testing the tensile strength of wire.

Born out of wedlock in 1452 to a

successful notary and a lower-class woman in the small town of Vinci,

he was educated in Florence by the Italian painter and sculptor Andrea del

Verrocchio. He began his career in

Florence, but then spent much time in Milan in the service of Ludovico

Sforza, the Duke of Milan. Later, he

worked in Florence and Milan again, as well as briefly in Rome, all while

attracting a large following of imitators and students. Upon the invitation of French King Francis

I, he spent his last three years in France, where he died in 1519 at the age of

67.

Principal locations of Leonardo da Vinci’s life events and artistic efforts in Italy.

In addition to his painting and

inventions, Leonardo Da Vinci made substantial contributions to many

science and engineering disciplines, including anatomy,

botany, cartography, chemistry, civil engineering, hydrodynamics,

geology, mathematics, mechanical engineering, optics,

physics, and physiology.

Da Vinci’s curiosity and insatiable hunger for knowledge

never left him. He was constantly

observing, experimenting, and inventing, and drawing was, for him, a tool for

recording his investigation of nature.

Although completed works by Leonardo are few, he left a large body

of drawings (almost 2,500) with notes that record his

ideas, most still gathered into notebooks.

One special feature that makes

Leonardo’s notes and sketches unusual is his use of cursive mirror image writing,

without punctuation. It is uncertain why

he chose to do so.

Leonardo da Vinci’s genius as an artist, inventor, and man of

science continues to inspire artists and scientists alike, centuries after his

death.

Birth and Childhood: 1452 - 1466

Leonardo da Vinci was born on April

15, 1452 in the Tuscan hill town of Vinci, in the lower valley of the Arno

River in the territory of Florence. He

was the illegitimate son of Ser Piero, a prominent Florentine notary and

landlord, and Caterina di Meo Lippi, a young peasant girl.

Little is known about Leonardo's

childhood. His

early years were spent living on his father’s family estate in Vinci; raised by

his father and several stepmothers.

Leonardo only received a basic elementary education

in writing, reading, and mathematics, possibly because his artistic talents

were recognized early, so his family decided to focus on art.

Apprenticeship with Verrocchio in

Florence: 1466 - 1476

In the mid-1460s, Leonardo's family

moved to Florence. Around the age of 14,

Leonardo became a studio boy in the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio, who

was the leading Florentine painter and sculptor of his time. Verrocchio

was the officially recognized sculptor for the Medici family, the rulers of

Italy during this era.

Leonardo became an apprentice by the

age of 17. In 1472, at the age of 20,

Leonard had progressed sufficiently to become a member of the Florence Painters' Guild,

although he continued his studies with Verrocchio as an assistant until 1476.

Under Verrocchio's tutelage, da Vinci

probably progressed from doing various menial tasks around the studio to mixing

paints and preparing surfaces. He would

have then have graduated to the study and copying of his master's works. Finally, he would have assisted Verrocchio,

along with other apprentices, in producing the master's artworks. (Much of his other creative output during his

time with Verrocchio was credited to the master of the studio although the

paintings were collaborative efforts.)

In 1473, when he was more than halfway

through his studies with Verrocchio, Leonardo completed Landscape Drawing for Santa Maria della Neve, a pen and ink depiction of the Arno

River Valley. It is the earliest work

that is clearly attributable to Leonardo da Vinci.

This landscape drawing is the earliest work that is clearly attributable to Leonardo da Vinci (1473).

The influences of Verrocchio are

evident in the remarkable vitality and anatomical correctness of the later

paintings and drawings by Leonardo da Vinci.

Leonardo was also influenced by other

famous painters apprenticed in the workshop, or associated with it, like Sandro

Botticelli, who would later contribute to the frescoes in the Sistine Chapel,

and paint the immortal The Birth of Venus. Leonardo was also profoundly influenced by

the works of great artists ornamenting the city of Florence.

Leonardo da Vinci not only developed

his skill in drawing, painting, and sculpting during his apprenticeship, but

through others working in and around the studio, he picked up knowledge in such

diverse fields as mechanics, carpentry, metallurgy, architectural drafting and

chemistry.

First Florentine Period (1477 - 1482)

After leaving the Verrocchio studio to

set up his own studio in Florence, Leonardo da Vinci began laying the

groundwork for his artistic legacy. Like

his contemporaries, he focused on religious subjects, but he also took portrait

commissions as they came up. Over the

next five years or so, he produced several notable paintings, including Madonna

of the Carnation, Ginevra de Benci, Benois Madonna, Adoration

of the Magi, and St. Jerome in the Wilderness.

In 1478, Leonardo received a

commission to paint the Adoration of the Magi from Florence church

elders who planned to use it as an altarpiece in the Chapel of Saint Bernard in

the Palazzo Vecchio. This artwork

is historically significant by virtue of the innovations da Vinci made that

were unique among the art conventions of the 1480s. He centered the Virgin and Christ child in

the scene whereas previous artists had placed them to one side. Da Vinci improved on standard practices of

perspective by making changes in clarity and color as objects became

increasingly distant.

The Adoration of the Magi - one of da Vinci’s unfinished paintings.

Unfortunately, he did not complete the

commission, abandoning his work, when the Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza, hired

da Vinci as the resident artist at his court. (Leonardo had written Sforza a letter which

described the diverse things that he could achieve in the fields of engineering

and weapon design, and mentioned that he could paint.)

There are a great many

superb surviving pen and pencil drawings from this period, including many

technical sketches - for example, pumps, military weapons, mechanical apparatus

- that offer evidence of Leonardo’s interest in, and knowledge of, technical

matters even at the outset of his career.

First Milanese Period (1482 - 1499)

Leonardo worked in Milan from 1482

until 1499. He was commissioned to paint

the Virgin of the Rocks for the Confraternity of the

Immaculate Conception and The Last Supper for the monastery

of Santa Maria delle Grazie.

Virgin of the Rocks is a

six-foot-tall altarpiece, also called the "Madonna of the Rocks." In

this painting, which dates to 1483, Leonardo experimented with blending the

edges of objects in indistinct light to create a sort of smoky effect known as

sfumato, a technique da Vinci would continue to develop in his future works.

Virgin of the Rocks dates to 1483.

It was perhaps because of his desire

to fine-tune this technique that his other surviving painting from his years in

Milan, The Last Supper, a 15 x 29-foot wall painting in the refectory of the monastery of Santa Maria delle

Grazie, completed in 1498, deteriorated so quickly. Da Vinci used oil-based paint on plaster for

this scene of Jesus and his apostles at the table because his customary

water-based fresco paints were difficult to blend for the sfumato effect he

sought. Within only a few decades, much

of the painting had flaked away from the wall.

The canvas of Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper that now hangs in

the Louvre is, in large part, a reproduction of the failed fresco.

Leonardo’s gracious but reserved

personality and elegant bearing were well-received in Milan’s court circles. Highly esteemed, he was constantly kept busy

as a painter and sculptor and as a designer of court festivals. He was also frequently consulted as a

technical adviser in the fields of architecture, fortifications, and

military matters, and he served as a hydraulic and mechanical engineer. As a master

artist, Leonardo maintained an extensive workshop in Milan, employing

apprentices and students.

On his own, Leonardo completed his

drawing of the Vitruvian Man in 1490. Inspired by the writings of the

ancient Roman architect Vitruvius, the drawing depicts a nude man in two

superimposed positions with his arms and legs apart and inscribed in both a

circle and square. The drawing

represents Leonardo's conception of ideal body proportions.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man (1490).

Second Florentine Period (1500 - 1508)

When Milan and Ludovico Sforza were overthrown

by France in 1500, Leonardo fled Milan for Venice, where the governing council sought his advice on how to ward off a

threatened Turkish incursion in northeast Italy. Leonardo

recommended that they prepare to flood the menaced region.

On his return to Florence in 1500, he

was a guest of the Servite monks at the monastery of Santissima Annunziata, and

was provided with a workshop. His

reputation preceded him; after a long absence, he

was received with acclaim and honored as a renowned native son.

Starting in 1501, Leonardo made

preliminary progress on his painting, Virgin and Child with Saint

Anne, which he would set aside unfinished, not to be completed for another 18

years.

Leonardo started Virgin and Child with Saint Anne in 1501, but didn’t complete it until 1519.

In 1502, Leonardo briefly entered the

service of Cesare Borgia, the son of Pope Alexander VI, in Cesena,

east of Florence, near the Adriatic Sea, acting as a military architect and

engineer and traveling for 10 months throughout Italy with his patron. Leonardo surveyed the territory and in the

course of his activity, he sketched some of the city plans and topographical

maps, creating early examples of aspects of modern cartography.

Leonardo left Borgia's service and

returned to Florence by early 1503. He

began working on a portrait of Lisa del Giocondo, the model for the Mona Lisa,

which he would continue working on until his twilight years, and never finish.

In approximately the same period, Leonardo

created his second version of the painting, Virgin of the Rocks. Chief differences between the two versions

include color choices, lighting and details of composition.

The second Florentine period was also

a time of intensive scientific study. Leonardo did dissections in the hospital of

Santa Maria Nuova and broadened his anatomical work into a comprehensive study

of the structure and function of the human organism. He made systematic observations of the flight

of birds, about which he planned a treatise. Even his hydrological studies, “on the nature

and movement of water,” broadened into research on the physical properties of

water, especially the laws of currents, which he compared with those pertaining

to air.

Leonardo da Vinci returned to Milan in

1506 to accept an official commission for an equestrian statue. However, he did not stay in Milan for long

because his father had died in 1504, and in 1507, he was back in Florence

trying to sort out problems with his brothers over his father's estate. In 1508, Leonard returned to Milan.

Second Milanese Period

(1508 - 1513)

Honored and admired by his generous

patrons in Milan, Charles d’Amboise and French King Louis XII,

Leonardo enjoyed his duties, which were limited largely to advice in architectural

matters.

During this second period in Milan,

Leonardo created very little as a painter.

But over the course of this seven-year

residency in the city, Leonardo would produce a body of drawings on topics that

ranged from human anatomy to botany, plus sketches of weaponry inventions and

studies of birds in flight. The latter

would lead to his exploratory drawings of a human flight machine. All of his drawings during this time reflected

da Vinci's interest in how things are put together and how they work.

Leonardo’s scientific activity

flourished during this period. His

studies in anatomy achieved a new dimension in his collaboration with

Marcantonio della Torre, a famous anatomist from Pavia (20 miles south of

Milan). Leonardo outlined a plan for an

overall work that would include not only exact, detailed reproductions of

the human body and its organs, but would also

include comparative anatomy and the whole field

of physiology. Beyond that, his

manuscripts are replete with mathematical, optical, mechanical, geological, and

botanical studies.

Rome and France (1513 -

1519)

In 1513, political events - the

temporary expulsion of the French from Milan - caused the now 60-year-old

Leonardo to move again. At the end of

the year, he went to Rome, hoping to find employment there through his

patron Giuliano de Medici, brother of the new pope, Leo X. Giuliano gave Leonardo

a suite of rooms in his residence, the Belvedere, in the Vatican.

He also gave Leonardo a considerable monthly stipend, but no large commissions followed.

For three years Leonardo remained in

Rome at a time of great artistic activity: Donato Bramante was building St. Peter's, Raphael was painting the last rooms of the pope’s new

apartments, and Michelangelo was struggling to complete the tomb of

Pope Julius II. Drafts of embittered letters betray the

disappointment of the aging master, who kept a low profile while he worked in

his studio on mathematical studies and technical experiments, or surveyed

ancient monuments as he strolled through the city.

At age 65, Leonardo accepted the invitation

of the young King Francis I to

enter his service in France.

At the end of 1516, he left Italy forever.

Leonardo spent the last three years of his life in a small residence in

Cloux, near the king’s summer palace in central France. He proudly bore the title “First painter,

architect, and engineer to the King.”

Leonardo still made sketches for court

festivals, but the King treated him in every respect as an honored guest and

allowed him freedom of action.

Leonardo did little painting while in

France, spending most of his time arranging and editing his scientific

studies. But many historians believe

Leonardo completed his final painting, St. John the Baptist, an oil

painting on walnut wood, at his rural home in Cloux, France. This masterwork exhibits his perfection of

the sfumato technique.

Leonardo da Vinci’s last painting - John the Baptist (1516).

Leonardo became ill, in what may have

been the first of multiple strokes. He continued to work at some capacity until

eventually becoming bedridden for several months. His ill health may indicate why he left works such as the Mona

Lisa unfinished.

Leonardo da Vinci died at Cloux on May 2, 1519 at the age of 67, and was buried in

the palace church of Saint-Florentin.

The church was devastated during the French Revolution and

completely torn down at the beginning of the 19th century; his grave

can no longer be located.

Legacy

Within the artworks created by his own

circle of peers, the influence of Leonardo da Vinci's painting is readily

evident. Raphael, and even sometimes rival Michelangelo,

adopted some of da Vinci's signature techniques (such as the use of light,

perspective, sfumato, his unique placement of key figures, his innovative

techniques for laying on the paint, and his scientific investigations of the

human body) to produce similarly active, anatomically realistic figures.

Leonardo’s innovative breaks from the

artistic standards of his day would guide generations of artists that followed.

In The Last Supper, the way

in which he isolated Christ at the epicenter of the scene and made each apostle

a separate entity, yet at the same time united them all in the moment, is a

stroke of genius that subsequent artists throughout history would strive to

replicate.

Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1498).

To the present day, art enthusiasts

worldwide consider the iconic Mona Lisa to be among the greatest

paintings of all time. An aura of

mystery surrounds this painting, which is veiled in a soft light, creating an

atmosphere of enchantment. There are no hard lines or contours here, only

seamless transitions between light and dark. Perhaps the most striking feature

of the painting is the sitter’s ambiguous half smile. She looks directly at the

viewer, but her arms, torso, and head each twist subtly in a different

direction, conveying an arrested sense of movement.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (unfinished).

Her image continues to appear on items

ranging from T-shirts to refrigerator magnets, and rather than trivializing the

import of the masterpiece, this popularity serves to immortalize Leonardo da

Vinci's paintings and drawings. They

still remain at the forefront of people's hearts and minds centuries after his

death.

Although he had no formal academic

training, many historians and scholars regard Leonardo as the prime exemplar of

the "Universal Genius" or "Renaissance Man,” an individual of

"unquenchable curiosity" and "feverishly inventive

imagination." He is widely

considered one of the most diversely talented individuals ever to have lived. According to art historian Helen Gardner,

“the scope and depth of his interests were without precedent in recorded

history, and his mind and personality seem to us superhuman, while

the man himself mysterious and remote.”

Leonardo

da Vinci’s notebooks contain diagrams, drawings, personal notes and

observations, providing a unique insight into how he saw the world.

But Leonardo found it

difficult to bring his work to a conclusion, so he

never published the scientific work in his notebooks. These notebooks -

originally loose papers of different types and sizes - were largely entrusted

to Leonardo's pupil and heir Francesco Melzi after the master's death. They

were supposed to be published, but it was a task of overwhelming difficulty

because of its scope and Leonardo's idiosyncratic writing. For years, the

notebook largely languished in Melzi family possessions.

It wasn’t until the late 1500s, after Meizi’s death, that the

notebooks were rather haphazardly dispersed and began to be published in

pieces. The tragedy is that much of Da

Vinci’s scientific work was only re-discovered many years after his death at a

time when science had already embraced many of his ideas. (For decades

after his death, Leonardo was known only as a painter.) There is little doubt that

had his work been publicized in the Renaissance era it would have advanced the

knowledge of the time. His left-handed

mirror-writing also caused problems. It created a code that needed breaking

before his unpunctuated manuscripts could be understood. Also, many of his scientific papers have been

lost or damaged and are dispersed throughout the world.

Some works eventually found their way

into major collections such as the Royal Library at Windsor Castle, the

Louvre, the Biblioteca Nacional de España, the Victoria and Albert

Museum, the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, and the British

Library in London. Works have also

been at Holkham Hall, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and in private

hands.

Today,

there are eleven

surviving bound manuscripts of Leonardo

da Vinci’s notes and drawings, amounting to thousands of pages.

The notebooks

were influential both for their theories on painting and Leonardo’s diagrams on

perspective, but also on the pursuit of knowledge in general. Simply the way that Leonardo illustrated

certain subjects (from an embryo to a cathedral), with his use of

cross-section, perspective, scaled precision, and repeating the subject, but

from different viewpoints, would all influence draughtsmanship in architecture

and the creation of diagrams in science ever

after. Above all, Leonardo showed that

practice and theory could not and should not be separated. The great master demonstrated in his own

person that a full knowledge of any subject required a combination of the

skills of the artisan, the flair and imagination of the artist, and the

meticulous research and reasoning of a scholar. Consequently, the approaches to

a great many subjects, but especially art, architecture, engineering, and

science, were fundamentally changed forever.

Leonardo commands continued admiration

from painters, critics, and historians. The interest in Leonardo's genius has

continued unabated; experts study and translate his writings, analyze his

paintings using scientific techniques, argue over attributions, search for

works which have been recorded but never found, and marvel at his inventions

and notebooks.

On the 500th anniversary of

Leonardo's death, the Louvre in Paris arranged for the largest ever single

exhibit of his work, called Leonardo, between November 2019 and

February 2020. The exhibit included over

100 paintings, drawings and notebooks.

Comments

Post a Comment