HISTORY71 - Time Zones and Daylight Savings Time

Recently, most people in United

States moved their clocks an hour forward, observing Daylight Savings Time

(DST). I live in Arizona, which does not

observe DST (even though my “smart a_ _” bedside clock moved the time one hour

forward anyway). While resetting that

clock, I decided that the history of time zones and DST would be a good topic

for a blog.

After a short introduction, I will

cover the need for standard time, America’s first time zones, the idea of DST,

U.S. Congressional actions defining time zones and DST observance, U.S. time

zones today, DST controversies, and will finish with worldwide time zones and

DST observance.

My principal resources include

“Time Zone,” “Daylight Savings Time,” and “International Date Line,”

Wikipedia.com; “A Brief History of Time Zones,” geojango.com; “History of Time

Zones,” bts.gov; “Daylight Savings Time,” crsreports.congress.gov; “U.S. Time

Zones in 1918,” papershake.blogspot.com; “The History of and Use of Time

Zones,” thought.com; “US Time Zones: A History

Timeline,” familytreemagazine.com; plus, numerous other online sources.

Introduction

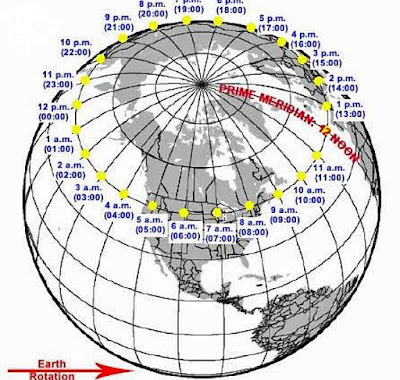

Time zones are regions on the Earth which observe a

uniform standard time. Particular

time zones are associated with local sun time (e.g., noon) and are usually one

hour ahead or behind their nearest neighbors. Time zones were initially conceived to make

better sense of long-distance railroad travel schedules, with time zone

boundaries going through major rail centers.

The next step was to associate time zone boundaries with the 24 hours of

Earth’s rotation in one day. Following

that basic formulation, time zones today are adjusted to follow the boundaries

between countries and their subdivisions (e.g., U.S. states) because

it is convenient for areas in frequent communication to keep the same time. See the figure above.

Daylight saving time (DST)

is the practice of advancing clocks (typically by one hour) during warmer

months so that darkness falls at a later clock time - for energy savings and

economic reasons. The typical

implementation of DST is to set clocks forward by one hour in the spring

("spring forward"), and to set

clocks back by one hour in the fall ("fall back")

to return to standard time.

Need for Standard Time

Prior to the late 1800s, timekeeping

was a purely local phenomenon. Each town

would set clocks to noon when the sun reached its zenith each day. A clockmaker or town clock would be the

"official" time, and the citizens would set their pocket watches and

clocks to the time of the town.

Enterprising citizens would offer their services as mobile clock

setters, carrying a watch with the accurate time to adjust

the clocks in customer's homes on a weekly basis. Travel between cities meant having to change

one's pocket watch upon arrival. There were over 144 local times throughout the United States during

this time.

However, once railroads began to

operate and move people rapidly across great distances, time keeping became

much more critical. In the early years

of the railroads, the schedules were very confusing because each stop was based

on a different local time.

Each

railroad used its own standard time, usually based on the local time of its

headquarters or most important terminus, and a railroad's train schedules were

published using its own time. Some

junctions served by several railroads had a clock for each railroad, each

showing a different time. Due to lack of time standardization,

schedules on the same tracks often could not be coordinated, resulting in

collisions.

The need for standardized time grew

more urgent with the expansion of the railroads. When the Golden Spike completed the first

Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, the time was 12:45 p.m. at the site in

Promontory Point, Utah; but 12:30 p.m. in Virginia City, Nevada.; 11:44 a.m. in

San Francisco; and 2:47 p.m. in Washington, DC.

The railways’ 53,000 miles of tracks operated according to at least 80

different timetables.

Railroad Time

In 1878, Scottish-born,

Canadian engineer Sir Sandford Fleming proposed the system of

worldwide time zones that we use today.

He recommended that the world be divided into 24 time zones, each spaced

15 degrees of longitude apart. Since the

Earth rotates once every 24 hours, and there are 360 degrees of longitude, each

hour the Earth rotates one-twenty-fourth of a circle or 15 degrees of

longitude. Sir Fleming's time zones were

heralded as a brilliant solution to a chaotic problem worldwide.

Sir Sanford Fleming proposed the system of worldwide time zones that we use today.

The American Meteorological Society’s

1879 “Report on Standard Time” helped push American railroad companies to

institute a version of Fleming’s plan.

As a result, in 1883, the major American railroad companies began to operate on a

coordinated system of five time zones:

the familiar Eastern, Central,

Mountain, and Pacific, plus the Intercolonial time zone in the northeast corner of

Maine. Within

a year, 85% of all cities with populations over 10,000 (about 200 cities) were

using railroad standard time.

Chicago and Alton Railroad 1884 map of the U.S. - showing time zones of railroad standard time.

In 1884, under Fleming’s leadership,

an International Prime Meridian Conference was held in Washington D.C. to

standardize time across the world, and to select the prime meridian, from which longitude and time would be measured. The conference selected Greenwich, England as

zero degrees longitude, and established the 24 time zones based on the prime

meridian.

Fleming’s worldwide time zones at 15-deg- longitude intervals. Time is measured from the prime meridian as shown.

Although many U.S. states began

adopting the use of time zones shortly after this conference, the limits of the standard time zones were

fixed only by custom of cross-continent railroads, or by local law.

The Idea of Daylight Savings Time

Meanwhile, the idea of DST time to

provide an additional hour of sunlight in summer months, began to be

discussed. In 1895, England-born New

Zealander George Vernon Hudson, a specialist in insect biology (entomology,)

presented the idea of an annual two-hour DST shift to the Royal Society of New

Zealand, but was mocked. Other members

of the Society deemed the proposal confusing and unnecessary.

In 1895, George Vernon Hudson first proposed the idea of Daylight Savings Time.

In 1907, British builder William Willett presented

the DST idea as a way to save energy, but after serious consideration by the

British government, it was not implemented.

The outbreak of the First World War made the issue

more important, primarily because of the need to save coal. Both Germany and Britain introduced one-hour

year-round DST in 1916 as a temporary wartime production-boosting device, and

it was subsequently adopted in many other countries.

Key

U.S. Congressional Actions

In

the Standard Time Act of 1918, passed during World War I, Congress established that standard time in the

United States be divided into five time zones (Eastern [now including the entire

state of Maine], Central, Mountain, Pacific, and Alaska), created by the

Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) in essential concurrence with zones

previously established by the national railroad system. It also authorized the ICC to change time

zones boundaries as necessary. But American

adherence to the new time zones remained voluntary.

|

| Continental U.S. time zones defined by the Standard Time Act of 1918 - reconstructed from news reports of boundaries from the Interstate Commerce Commission. |

The Standard Time Act also instituted the nation’s first seasonal DST for

the entire country, dictating that on the last Sunday of March each year, the clock

be advanced an hour, and then returned an hour on the last Sunday of October of

that same year - in an effort to save fuel.

Poster board for saving daylight during World War I.

This

controversial wartime measure was repealed the next year at the

federal level, although it remained a local option with some states continuing

to observe it.

In 1942, during World War II, Congress

implemented year-round DST for the country on a temporary basis that advanced

the standard time for each time zone by one hour. After the conclusion of World War II, on the

last Sunday in September 1945, Congress terminated full time DST.

For two decades after World War II,

standard time was voluntary across the U.S., producing “growing inconvenience,

confusion, and sometimes danger.” For example, bus drivers on a 35-mile stretch of Route 2 between

Moundsville, West Virginia, and Steubenville, Ohio, had to reset their watches

seven times.

This situation caused Congress to pass

the Uniform Time Act of 1966, mandating standard time within the established

time zones.

The Act also restored annual DST,

specifying that: clocks would be advanced one hour beginning at 2:00 a.m. on

the last Sunday in April, and turned back one hour at 2:00 a.m. on the last

Sunday in October. States were allowed

to exempt themselves from DST as long as the entire state did so. The ICC was authorized with

implementing the act until authority was transferred to the Department of

Transportation later in 1966.

Continued Congressional Action

Over the years, Congress made several

changes to time zone and DST laws.

In 1972, the Uniform Time Act was

amended to also allow states that were split between time zones to exempt from

DST that part of the state lying within a different time zone.

During the 1973 oil embargo by the

Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries, Congress enacted the

Emergency Daylight Saving Time Energy Conservation Act of 1973, which

established a temporary period of year-round DST, from January 6, 1974, to

April 27, 1975.

In 1986, Congress changed the

beginning of annual DST from the last Sunday in April to the first Sunday in

April.

In 2005, Congress further changed annual

DST to begin the second Sunday in March and end the first Sunday in November;

this DST period remains in effect today.

Today’s U.S. Time Zones

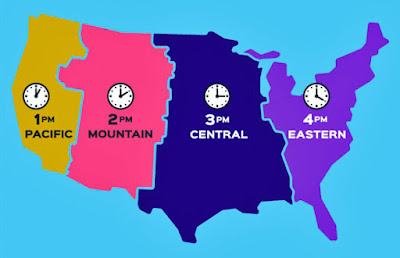

There are currently nine time zones in the U.S. and its

territories, they include Eastern, Central, Mountain, Pacific, Alaska,

Hawaii-Aleutian, Samoa, Wake Island, and Guam.

The following U.S. states and

territories do not observe DST: most of Arizona, Hawaii, American Samoa, the

Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands.

In 1973, Arizona was granted, a DST exemption,

because of the extreme heat in summer months.

However, the Navajo Nation, occupying considerable land in northeastern

Arizona does observe DST, to be consistent among all of its territory, which

stretches into Utah and New Mexico. Along

with most of Arizona, the Hopi Nation, enclosed by the Navajo Nation, does not

observe DST.

Hawaii abandoned DST in 1967 because it

didn’t make sense. One of the benefits

of DST is that there’s more daylight in the evening. But in Hawaii, the sun rises and sets at about

the same time every day - all year long.

Current United States time zones; also shows areas that do not observe Daylight Savings Time.

Daylight Savings Time Controversy

DST has been controversial since its

first use in 1918. In 1974, Congress

required several agencies to study the effects of changes in DST observance,

including the potential benefits to energy conservation, traffic safety, and

reductions in violent crime; results in all cases were minimal. In 2008, the Department of Energy assessed

the effects on national energy consumption of extending DST as minimal. Other studies have examined potential health

effects associated with the spring and fall transition to DST and found a measurable

cumulative effect of sleep loss and increased risk for incidence of acute heart

attacks in specific subgroups. Various

legislative attempts to change DST have been proposed, but so far, none have

passed Congress.

Since 2015, at least 45 states have

proposed legislation to change their observance of DST. Most of the proposals have not passed. Eleven states have enacted permanent DST

legislation: Delaware, Florida, Idaho, Louisiana, Maine, Oregon, South

Carolina, Utah, Tennessee, Washington, and Wyoming. In addition, Arkansas and Georgia have

adopted resolutions in support of permanent DST.

Worldwide Time Zones and

Daylight Savings Time

By about 1900, almost all inhabited places on Earth had adopted

a standard time zone, but only some of them used an hourly offset from the time

at the prime meridian at Greenwich, England (called Greenwich Mean Time or GMT).

Many applied the time at a local

astronomical observatory to an entire country, without any reference to

Greenwich. It took many decades before

all time zones were based on a standard offset from GMT. By 1929, the majority of countries had adopted

hourly time zones, based on Sir Sanford Fleming’s proposals.

Today, out of the 195 countries

in the world, 23 have at least two distinct time zones. The country with the most total time zones is

France with 12, which takes into consideration their many overseas territories.

Following France is Russia with

11 time zones. The Trans-Siberian

Railway, which travels between the Russian cities of Moscow and Vladivostok,

passes through 10 distinct time zones over the course of its six-day journey!

The United States follows

Russia with nine official time zones and two unofficial time zones, which also

takes into account overseas research stations and territories.

Surprisingly, a select few

countries that are large enough to contain numerous time zones only adhere to a

single time zone. China and India are

the most famous examples. China's single

time zone actually spans five distinct time zone regions, or 75 degrees of longitude,

which makes it the largest single time zone in the entire world. However,

while there is only one official time zone, much of the population abides by

unofficial time zones that may be ahead of, or behind, China Standard Time.

Although most countries use

time zones that differ by exactly one hour, some countries actually use half

hour or quarter hour time zones. These

include India, Iran, Afghanistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and certain

regions of Australia.

Current worldwide standard time zones, showing adjustment from the 15-deg longitude meridians and time differences from the prime meridian.

In the figure above, note the

International Date Line in the mid Pacific Ocean. The International Date Line is an internationally

accepted demarcation on the surface of Earth, running between

the South and North Poles, and serving as the boundary

between one calendar day and the next. It roughly follows the 180-degree line of

longitude, deviating to pass around some territories and island groups. Crossing the date line eastbound decreases the

date by one day, while crossing the date line westbound increases the date.

The International Date Line is the boundary between one calendar day and the next.

Since time zones are based on segments of longitude, and lines

of longitude narrow at the poles, scientists working at the North and South

Poles simply use the time at the prime meridian (0-degree longitude).

A minority of the

world's population uses DST; Asia, Africa, and Latin America, and the Caribbean

generally do not.

DST is generally not

observed near the Equator, where sunrise and sunset times do not vary enough to

justify it. Conversely, it is not

observed at some places at high latitudes, because there are wide variations in

sunrise and sunset times, and a one-hour shift would relatively not make much

difference.

A

move to permanent DST is sometimes advocated and is currently implemented in

some jurisdictions such as Argentina, Belarus, Iceland, Kyrgyzstan, Morocco,

Namibia, Saskatchewan, Singapore, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan

and Yukon.

Nowadays, our electronic devices can keep track of multiple time zones (perhaps those that you call regularly for business or family matters), and even automatically adjust your personal time zone when you travel.

Comments

Post a Comment