HISTORY69 - Native Americans in the Lower Mississippi River Valley

Pat and I were looking forward to

a Spring 2023 cruise on the Lower Mississippi River from New Orleans to

Memphis. In preparation for that adventure,

I previously wrote about the history of the Mississippi River (February 27,

2022) and the history of New Orleans (April 15, 2022). I planned on this article covering the

history of Native Americans in the Lower Mississippi River Valley, and then

following that with an article on the history of Memphis. Unfortunately, our trip was cancelled during

the writing of this article. I decided

to complete the article anyway. You

never know …

After a short introduction to the

Lower Mississippi River, I will cover the first peoples in the area, then over

5,000 years of impressive Mound Builder cultures, the first European contact,

post contact Native American cultures, the ensuing Indian wars, and Indian

removals, in which Native Americans lost their heritage lands. I will conclude with a snapshot of Native

Americans in the Lower Mississippi River Valley today.

My principal sources include Atlas

of the North American Indian by Carl Waldman; “Native American Archaic

Cultures,” and “Mississippian Culture,” britannica.com; “Mound Builders,”

“Watson Brake,” “Hopewell Tradition,” “Mississippian Culture,” “Chucalissa,”

“Winterville Site,” and “List of Indian Reservations in the United States,” wikipedia.com;

“Hopewell Culture,” crt.state.la.us; “Mississippian Culture,”

courses.lumenlearning.com; “Southeast Culture Area,” kids.britannica.com; “Profile:

American Indian / Alaska Native,” minorityhealth.hhs.gov; and numerous other

online sources.

Introduction

The Mississippi River is one of the world’s major river

systems in size, habitat diversity, and biological productivity. It is also one of the world's most important

commercial waterways and one of North America's great migration routes for both

birds and fishes. The Mississippi River began flowing some 70 million

years ago, when dinosaurs still roamed the planet.

The Mississippi River is the second longest river in North

America, flowing 2,340 miles from its source at Lake Itasca in northern

Minnesota, generally south through the center of the continental United States

to New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico.

Generally, the Lower Mississippi River is defined as the

portion of the river downstream of Cairo, Illinois, where the Ohio River joins

the Mississippi, some 954 miles from the Gulf of Mexico. For the purposes of this article, I will refer

to the portion of the Mississippi River downstream of Memphis, Tennessee as the

Lower Mississippi, a river distance of 737 miles.

|

| The Lower Mississippi River - between Memphis and the Gulf of Mexico. |

First Peoples

The

Lower Mississippi River basin was first settled by ancient hunting - gathering people about 10,000 years ago. During the Archaic period, from 8000 BC to

1000 BC, these first peoples transitioned from hunting large mammals and exploitation

of nuts, seeds, and shellfish, to hunting smaller animals, and sedentary

farming. Evidence of early cultivation of

sunflower, goosefoot, marsh elder plants for seeds, and indigenous

squash, dates to the 4th millennium BC.

Mound Builders

A

number of pre-Columbian cultures in today’s Eastern United States are

collectively termed Mound Builders.

The term does not refer to a specific people or archaeological culture,

but refers to the characteristic mound earthworks they erected. Geographically, the cultures were present in

the region of the Great Lakes, the Ohio River Valley, and

the Mississippi River valley and its tributary waters.

I’m

going to focus on those Mound Builder cultures that were present or had

significant influence in the Lower Mississippi River Valley. These cultures span the period of roughly

3500 BC to the 16th century AD - covering over 5000-years of Native

American history prior to first contact with Europeans. These cultures include the so-called Watson

Brake, Poverty Point, Hopewell, and Mississippian Cultures.

Watson

Brake. The first mound building was an early marker

of political and social complexity among the cultures in the Southeastern

United States. Watson Brake is the

oldest, largest, and most complex of these early mound sites in North

America.

Watson

Brake is located in the floodplain of the Ouachita River, near

present-day Monroe in northern Louisiana, about 90 miles west of

the Mississippi River and today’s town of Vicksburg, Mississippi.

Minor earthworks

were begun there around 3500 BC, and continued in stages until sometime after

3000 BC. The

mound complex consists of an oval formation of 11 earthwork mounds from three

to 25 feet in height, connected by ridges to form an oval nearly 900 feet

across. Watson Brake is older than the Ancient Egyptian

pyramids or Britain’s Stonehenge.

|

| Artist’s conception of Watson Brake mound complex. |

Watson

Brake’s discovery and dating in a paper published in 1997 changed the ideas of

American archaeologists about ancient cultures in the Southeastern United

States, and their ability to manage large, complex projects. The mound complex was developed over centuries

by a hunter-gatherer society, rather than by what was known to be more common

of other, later mound sites: a more sedentary society dependent on maize

cultivation and with a hierarchical, centralized government. Most archeologists today agree that local

natural resources were abundant enough to support mound builders and that

permanent status hierarchies were not necessary to get the job done.

Watson

Brake demonstrates that the pre-agricultural,

pre-ceramic, indigenous cultures within the territory of the

present-day United States were much more complex than previously thought. While primarily hunter-gatherers, they

planned and organized large work forces over centuries to accomplish the

complex mound and ridge constructions.

Workers dug up tons of earth with the hand tools available, moved the

soil long distances, and created the shape with layers of soil.

Waste dump remains show that the population relied on fish,

shellfish, and riparian animals, supplemented by local annuals: goosefoot,

knotweed, and possibly marsh elder. Over

time, the people consumed animals such as deer, turkey, raccoon, opossum,

squirrel, and rabbits - likely related to changing habitat and waterway

conditions.

Lacking pottery, the inhabitants heated

gravel to cook with. Hot rocks were

either used in hearths to provide a long-lasting heat source, or they were used

to “stone boil” liquids in containers like leather bags or gourds.

Watson Brake appears to have been abandoned around 2800 BC. After that, no

mounds were built in the Lower Mississippi River Valley for more than a

thousand years, until the Poverty Point site arose and brought mound building

to new heights.

Poverty

Point. The Poverty Point Culture, a

hunter-gathering society, inhabited a portion of the Lower Mississippi River Valley and

surrounding Gulf Coast from about 1730 - 500 BC. Archeologists have identified more than 100

sites belonging to this mound-builder culture. The people occupied villages that extended

for nearly 100 miles on either side of the Mississippi River, mostly in today’s

state of Louisiana, but some in southern Arkansas and southern Mississippi.

The Poverty Point site itself, located

near today’s town of Epps in northeastern Louisiana, about 50 miles northeast

of Watson Brake, was the “cultural capital” of the region. Other people in the area shared the Poverty

Point Culture, but they lived at smaller sites, built smaller mounds, and had

fewer fancy artifacts than at Poverty Point.

|

| Poverty Point Culture settlements extended over 100 miles on both sides of the Lower Mississippi River. |

The earthworks at Poverty Point are

the oldest earthworks of this size in the Western Hemisphere. In the center of the site is a plaza covering

about 37 acres. Archeologists believe

the plaza was the site of public ceremonies, rituals, dances, games, and other

major community activities.

The

huge site has six concentric earthworks, separated by ditches, or swales, where

dirt was removed to build a ridge structure. The ends of the outermost ridge

are three-quarters of a mile apart. The

ends of the interior embankment are over a third of mile apart. Originally, the ridges stood four to six feet

high and 140 to 200 feet apart.

Archeologists believe that the homes of 500 to 1,000 inhabitants were

located on these ridges. Poverty

Point’s design, with multiple mounds and C-shaped ridges, is not found anywhere

else.

Poverty

Point was the largest settlement at that time in North America. The site also

had a 50-foot high, 500-foot-long earthen pyramid, which was aligned east

to west. A large bird effigy mound, measuring 70

feet high and 640 feet across, is also located on the site. Additionally, the site had five smaller

conical mounds four to 21 feet high. No other

hunting and gathering society made mounds at this scale anywhere else in the

world. Unlike later mound builders,

Poverty Point residents did not use any of their mounds for burials.

|

| Artist’s conception of the huge Poverty Point site. |

Many people lived, worked, and held

special events at this huge site over hundreds of years. This has led some to

call it North America’s first city.

Archeological

excavation has revealed a wealth of artifacts, including animal effigy figures,

hand-molded baked-clay cooking objects, simple thick-walled pottery, stone

vessels, spear points, axes, hoes, drills, edge-retouched flakes, and blades.

Stone cooking balls were used to prepare meals. Scholars believe dozens

of the cooking balls were heated in a bonfire and dropped in pits along with

food. Different-shaped balls regulated

cooking temperatures and cooking time.

Artifacts of crude human figures are thought to have been used for

religious purposes.

Poverty Point was at the heart of a

huge trade network, the largest in North America at that time. This is unusual because the people did not

grow crops or raise animals for food. Weights were fashioned out of

heavy iron ore imported from Hot Springs, Arkansas, to sink fish

nets. Points made of imported gray Midwestern flint were also

found. Many of the raw materials used,

such as slate, copper, galena, jasper, quartz, and soapstone,

were from as far as 620 miles away, attesting to the distant reach of the

trading culture.

The

Poverty Point Culture developed a tradition of making high-quality, stylized,

carved, and polished miniature stone beads. The beads depicted animals common

to the Poverty Point Culture's environment, such as owls, dogs, locusts, and

turkey vultures.

The city flourished through 1100 BC, but the population seems

to have declined after this time, and the city was abandoned sometime before

500 BC.

Hopewell

Culture. About 200

BC, the Hopewell Culture began to flourish along rivers in what is now Illinois

and Ohio. Hopewell groups shared four

traits. First, they built groups of

mounds and embankments, some of which covered hundreds of acres and reached 50

feet in height. Second, they had

elaborate graves inside some mounds.

Third, they made artifacts of materials that came from far away. Fourth, they made special styles of decorated

pots and pipes.

Hopewell

society was hierarchical and village-based; surplus food was controlled by

elites who used their wealth to support highly skilled artisans and the

construction of elaborate earthworks. An

outstanding feature of Hopewell Culture was a tradition of placing elaborate

burial goods in the tombs of individuals or groups. The interment process involved the

construction of a large box-like log tomb, the placement of the body or bodies

and grave offerings inside, the immolation of the tomb and its contents, and

the construction of an earthen mound over the burned materials.

Artifacts found

within these burial mounds indicate that the Hopewell obtained large quantities

of goods from widespread localities in America -

including obsidian and grizzly bear teeth from as far away

as the Rocky Mountains; copper from the northern Great Lakes;

and conch shells and other materials from the southeast and along the

coast of the Gulf of Mexico.

Many

Hopewell groups practiced agriculture, growing a variety of crops, including

corn, beans, and squash. Their extensive

villages usually near water, consisted of circular oval dome-roofed wigwams,

covered with animal skins.

Hopewell ideas swept across most of

eastern America and down the Mississippi Valley to the Gulf of Mexico,

including the Miller and Markville Cultures in the Lower Mississippi River Valley. (See the map below.) Each community decided which customs to

follow and how to change them to fit their way of life.

|

| The Hopewell Tradition (200 BC - AD 500) spread from Ohio and Illinois to the Midwest and most of eastern America. |

The

Hopewell tradition was not a single society but a widely dispersed set of

populations connected by a common network of trade routes, that lasted

until about AD 500.

Miller

Culture. The Miller Culture was located in

the upper Tombigbee Rover drainage areas of southwestern Tennessee, northeastern

Mississippi, and west-central Alabama.

Some sites associated with the Miller Culture had large platform mounds. Archaeologist

speculate the mounds were for feasting rituals.

In about AD 1000, the Miller Culture area was absorbed into the

succeeding Mississippian Culture.

Marksville

Culture. The Marksville Culture was

located in the Lower Mississippi Valley, Yazoo valley, and Tensas valley

areas of present-day Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Arkansas.

It is named for the Marksville Site in Marksville, Louisiana.

The Hopewell customs followed at

Marksville were 1) mounds and embankments, 2) burial traditions, and 3) pottery

decorations.

The Marksville site in central

Louisiana had six mounds and one ring enclosed by a C-shaped earthen

ridge. One of the mounds at Marksville

was a burial mound. Some of the tombs in

this mound were built with logs and cane mats.

Other earthworks, including a circle

and more rings, are outside the embankment.

Marksville covered at least 60 acres and was the largest site in use in

Louisiana at that time. It was a place

where people gathered for ceremonies and to mourn the dead; no houses have been

found at Marksville. People used the

site from AD 1 to AD 400.

Pottery is the major example of the

long-lasting effect that Hopewell traditions had in Louisiana. Other Hopewell traits were less widely

adopted in this region. For example,

earthen embankments and elaborate tombs in mounds were very rare, and

Marksville is unusual because it had these.

Marksville people gathered certain

plants; harvested wild grapes, persimmons, and berries; and hunted deer and

rabbits. In the forests east of the

site, nuts like acorns and pecans were available. Although Hopewell people to the north at

this time grew some crops in gardens, the people at Marksville did not. They

ate only wild plants. They also hunted animals like turtle and birds. Nearby rivers allowed for fishing and

gathering fresh water clams.

Note:

From here on in this paper, I’m dropping the anno Domini (AD) notation

for dates.

Mississippian

Culture. About 700, a new advanced agricultural

culture arose in the Mississippi River valley between the present-day cities

of St. Louis and Vicksburg. Known as the Mississippian Culture, it

rapidly spanned much of the present Midwestern,

Eastern, and Southeastern United States, including the Lower Mississippi River

valley.

|

| The Mississippian Culture (700-1500) expanded from the middle Mississippi River Valley to the Midwest, the East, and Southeast, including the Lower Mississippi River Valley. |

A network of trade routes was active along the waterways, spreading common cultural practices over the entire area between the Gulf of Mexico and the Great Lakes. Agriculture introduced from Mesoamerica, based on maize, beans, and squash, gradually came to dominate.

Small

native villages grew into large towns with highly stratified complex chiefdoms

and large populations, with subsidiary villages and

farming communities nearby.

Regional

styles of pottery, projectile points, house types, and other utilitarian

products reflected diverse ethnic identities. Notably, however, Mississippian peoples were

also united by two factors that cross-cut ethnicity: a common economy that

emphasized corn production and a common religion focusing on the veneration of

the sun and a variety of ancestral figures.

One

of the most outstanding features of Mississippian Culture was the

earthen temple mound. These

mounds often rose to a height of several stories and were capped by a flat

area, or platform, on which were placed the most

important community buildings - council houses and temples. Platform mounds were generally arrayed around

a plaza that served as the community’s ceremonial and social center; the plazas

were quite large, ranging from 10 to 100 acres.

Typical Mississippian mound complex.

The

most striking array of mounds occurred at the Mississippian capital

city, Cahokia, located near present-day St. Louis; some 120 mounds were

built during the city’s occupation.

Monk’s Mound, the largest platform mound at Cahokia, rises to

approximately 100 feet above the surrounding plain and covers some 14

acres. Cahokia, was occupied from about

600 to 1400 (Cahokia was settled around 600; mound building began with

the emergent Mississippian cultural period, around the 9th century.) At its

peak, the population of Cahokia numbered between 8,000 and 40,000 inhabitants,

larger than London, England at that time.

Artist’s conception of Cahokia, largest and most important of the Mississippian cities.

In

some areas, large, circular buildings received the remains of the dead, but

burial was normally made in large cemeteries or in the floors

of dwellings. Important household

industries included the production of mats, baskets, clothing, and a variety of

vessels for specialized uses, as well as the creation of regalia, ornaments,

and surplus food for use in religious ceremonies. In some cases, particular communities seem to

have specialized in a certain kind of craft activity, such as the creation of a

specific kind of pottery or grave offering.

Ritual and religious events were conducted by an organized priesthood

that probably also controlled the distribution of surplus food and other

goods. Core religious symbols such as

the weeping eye, feathered serpent, owl, and spider were found throughout the

Mississippian world.

As

the Mississippian Culture developed, people increased the number and complexity

of village fortifications, and often surrounded their settlements with timber

palisades. This was presumably a response

to increasing intergroup aggression, the impetus for which seems to

have included control of land, labor, food, and prestige goods.

The

Mississippian peoples had come to dominate the Southeast by about 1200.

By

the early 16th century, Cahokia and many other Mississippian cities

had declined. But, when Europeans first

explored the Southeast during that period, the predominant native groups met

and described by Spanish and French explorers were remnants of the Mississippian

Culture.

Middle

Mississippian. The

term Middle Mississippian is also used to describe the core of

the classic Mississippian Culture area. This area covers the central

Mississippi River Valley, the lower Ohio River Valley, and most of the

Mid-South area, including western and central Kentucky, western Tennessee, and

northern Alabama and Mississippi. Sites

in this area often contain large ceremonial platform mounds, and residential

complexes, and are often encircled by earthen ditches and ramparts

or palisades.

Important

sites located in, or near, the Lower Mississippi River Valley include: 1) Moundsville, an influential regional political

and ceremonial center between the 11th and 16th

centuries, and 2) Parkin, 30 miles west of present-day Memphis, believed by many archaeologists to have been

visited by Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto in 1542 (See below.)

Plaquemine. The Plaquemine culture was located in the Lower

Mississippi River Valley in western Mississippi and

eastern Louisiana. A good example

of this culture is Winterville, on the Mississippi River, north of Greenville,

Mississippi. It consisted of major earthwork

monuments, including more than twelve large platform mounds, and

cleared and filled plazas.

Artist’s conception of Winterville in the Lower Mississippi River Valley.

First

Contact with Europeans

Scholars

have studied the records of Spanish conquistador and explorer Hernando de

Soto's expedition of 1539 - 1543 to learn of his contacts with Mississippians,

as he traveled through their villages of the Southeast. On a winding route, the de Soto expedition

explored the present-day states (in the order listed) of Florida, Georgia,

South Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Texas. De Soto arrived at the Mississippi River at a

point below Natchez, Mississippi on May 8, 1541. De Soto was the first European documented to

have seen the Mississippi.

Note: Hernando de Soto

(c. 1500 - 21 May, 1542) was involved in early Spanish expeditions

in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He also played an important role

in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire in Peru, but de

Soto is best known for leading the first European expedition deep into the

Southeastern territory of the modern-day United States. De Soto died of a fever on 21 May, 1542, about

a year after reaching the Mississippi River.

Before his death, de Soto chose Luis de Moscoso Alvarado, his former

field commander, to assume command of the expedition, that continued into

Arkansas and Texas, then down the Mississippi River, and by sea to Mexico.

Painting of de Soto reaching the Mississippi River on May 8, 1541.

The

de Soto expedition met many varied Native American groups, most of

them bands and chiefdoms related to the widespread Mississippian Culture. De

Soto visited many villages, in some cases staying for a month or longer. Some

encounters were violent, while others were relatively peaceful.

De

Soto's encounters left about half of the Spaniards and perhaps many hundreds of

Native Americans dead. The chronicles of de Soto are among the first documents

written about Mississippian peoples and are an invaluable source of information

on their cultural practices.

Following

the de Soto expedition, the Mississippian peoples tried to continue their way

of life. However, this first contact by

Europeans dramatically changed these native societies. Because the natives

lacked immunity to infectious diseases unknowingly carried

by the Europeans, such as measles and smallpox, epidemics caused so many

fatalities that they undermined the social order of many chiefdoms. Political structures collapsed in many

places.

During

the 1500s, the native peoples of the Southeast suffered greatly as the

Spanish continued their explorations and sporadic colonization. Thousands of native people were killed during

warfare with explorers. Thousands more

died in epidemics of European diseases. Many other individuals were captured and

traded as slaves.

Post

Contact Native American Cultures (1543 - 1830)

The

remnants of the Mississippian groups dispersed from their heritage cities, and

over the next years of dramatic cultural change, were reborn in the so-called

Southeast Culture area as Native American tribes. Mississippian peoples were almost certainly

ancestral to many of these Native American nations. Among these Southeast peoples were

the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole,

which Europeans later called the Five Civilized Tribes. The map below shows the territory of these

tribes circa 1650.

The so-called five civilized Native American tribes in the Southeastern United States, circa 1650.

Other

prominent tribes in the Lower Mississippi Valley included the Natchez

(Louisiana), Caddo (Arkansas), Tunica (Louisiana/Arkansas/Mississippi), Coushatta

(southwest Louisiana), Chitimacha (southern Louisiana), and Quapaw (Arkansas). The Natchez were direct descendants of

the Mississippians. Many

other Southeast peoples also inherited cultural traits from the Mississippians,

such as the use of ceremonial mounds and a heavy reliance on corn.

The

economy of the Southeast tribes was mostly agricultural. The leading crop was corn, followed by beans

and squash. Southeast peoples also

raised sunflowers, which were processed for their oil, and tobacco. Wild plant foods, including greens, berries,

nuts, acorns, and sap, were readily available.

Native peoples also hunted deer, elk, black bears, beavers, squirrels,

rabbits, otters, raccoons, and turkeys.

Most

of the people lived in small villages, scattered along streams or in river

valleys. At the center of each town was

typically a council house or temple. Often these structures were set atop large

earthen mounds, as were the homes of the ruling classes or families. The heart of a town also included a central

plaza or square, and sometimes granaries or other structures for storing

communal produce.

Some

Southeast communities housed more than 1,000 people, but they more often had

fewer than 500 residents. A village

might be linked to neighboring settlements by ties of kinship, language, and

shared cultural traditions. Generally,

however, each village was independent and governed its own affairs. In times of

need, villages could unite into confederacies, such as those of Choctaw in the Lower

Mississippi River Valley.

Painting of a Choctaw village in the Lower Mississippi River Valley.

The

natives made many items of wood, including bows, arrow shafts, dishes, and

spoons. The inner bark of the mulberry

tree was used as thread and rope and in making textiles. Other important raw materials in the

Southeast included bone and stone, which were used to make arrowheads, clubs,

axes, scrapers, and other tools.

Southeast

tribes obtained copper through trade with western Great Lakes

peoples. They worked the metal to create beads, rings, and bracelets. Shells were used for beads and pendants, and

to decorate ritual objects.

A

lack of geographic barriers to the north and west allowed significant trade

with Northeast and Plains peoples.

The

main division of labor in the Southeast was by gender. Women were responsible for most farming,

gathering wild plant foods, cooking, and preserving food. They made baskets, pottery, clothing, and

other goods. Women also took care of

young children and elders. Men were

responsible for war, trade, and hunting; they were often away from the

community for long periods of time. Men also assisted in the harvest, cleared

the fields, and built houses and public buildings. Both women and men made ceremonial objects

and took part in building earthen mounds.

Indian Wars

During this period of post

contact Native American tribe development, colonization of America by European

powers accelerated.

In

1682, French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, canoed down the

Mississippi River from the mouth of the Illinois River to the Gulf of Mexico,

where he claimed the entire Mississippi River basin for France. With its first

settlements, France lay claim to a vast region of North America and set out to

establish a commercial empire and French nation stretching from the Gulf of

Mexico through Canada, including the Lower Mississippi River Valley. Meanwhile the English were expanding their

territory on the east coast of America, starting to move westward, while the

Spanish claimed Florida.

By the early 1700s, Southeastern Native American tribes found

themselves increasingly drawn into wars between European powers over control of

North America. Large tribes, including

the Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Cherokee, formed alliances with the

Europeans, and they often found themselves pitted against one another.

In 1729, in the Lower Mississippi River Valley, the Natchez

revolted against the French living in their midst but were defeated by a

combination of French and Choctaw, decimating the Natchez. From 1720 - 1752, the Chickasaw successfully

resisted repeated incursions of the French with their Choctaw allies.

Note: From 1754 - 1763,

the French and English fought the so-called French and Indian War for control

of American territory. The English won

the war, and the French lost all of their American territory.

During the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), the long-time

pro-British Chickasaw were active against American settlers as far north as

Kentucky, and the Chickasaw and Creek helped the British in several engagements

along the Lower Mississippi River.

On January 8, 1815, the Battle of New Orleans was fought between

the British Army and the United States Army under Brevet Major

General Andrew Jackson. This

battle, which the United State won, was the final battle of War of 1812. Native Americans were important to the American war

effort. Choctaw Indians assisted General

Jackson in New Orleans, and Caddo Indians, from North Louisiana, defended the

Louisiana-Texas border from invasions originating in Spanish controlled Texas.

Meanwhile, the number of Euro-American colonists in the

Southeast grew from perhaps 50,000 in 1690 to 1 million by 1790. The enslaved African population in the region

grew from about 3,000 to 500,000 during the same period. With these enormous population increases, the

Euro-American settlers demanded more land.

They were particularly interested in the large, prosperous farmland

owned by the Creek, Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw.

The

Creek War (1813-1814) began as a conflict among Creek factions, but soon involved

Spain, Britain, and the United States. British

traders in Florida, as well as the Spanish government, provided one Creek

faction with arms and supplies because of their shared interest in preventing

the expansion of the United States into their areas. Expansionist Americans, fearful that southeastern Indians would ally with

the British, quickly joined the war, turning the civil war into a military

campaign designed to destroy Creek power.

The U.S. formed an alliance with the Choctaw and Cherokee (both

traditional enemies of the Creeks).

The war effectively ended when General Andrew Jackson forced

the Creek confederacy to surrender more than 21 million acres in what is now

southern Georgia and central Alabama.

In

1817, tensions grew between the Seminoles and settlers in Spanish colonial

Florida and the newly independent United States, mainly because enslaved

people regularly fled from Georgia into Spanish Florida,

prompting slaveowners to conduct slave raids across the border. A series of cross-border skirmishes escalated

into a war with the Seminoles, when General Andrew Jackson led an

incursion into the territory over Spanish objections. Jackson's forces destroyed several Seminole towns

and briefly occupied Pensacola before withdrawing in 1818. The U.S. and Spain soon negotiated the

transfer of the Florida territory to the U.S. with the Adams-Onis

Treaty of 1819. The U.S. than coerced

the Seminoles into leaving their lands in the Florida panhandle for a

large Indian reservation in the center of the peninsula.

Indian

Removal

American

settlers began to call on the federal government for oppressive policies to

deal with the Native peoples. They

expanded their efforts after gold was found on Cherokee land in Georgia in

1829. In 1830 the U.S. Congress passed

the Indian Removal Act, which authorized President Andrew Jackson to grant

Native tribes unsettled western prairie land in exchange for their desirable

land in the East. The land west of the

Mississippi River that was designated for the Indians was called Indian

Territory (now Oklahoma).

The

Native peoples of the Southeast responded to the Indian Removal Act in a

variety of ways. The Choctaw arranged

their departure with federal authorities fairly quickly. The Chickasaw sold their property and planned

their own transportation to their new home.

By 1836, most Creeks had relocated

voluntarily or been forced to remove to Indian Territory. The Cherokee chose to use legal action to

resist removal, but the effort went nowhere.

Ultimately,

all the southeastern tribes found that resistance to removal was met with

military force. In the decade after 1830,

nearly every Native nation from the Southeast moved westward, whether

voluntarily or by force. Along the way

they encountered great difficulties and lost many people to exposure,

starvation, and illness. Those who

survived the migration named it the Trail of Tears.

From

the western side of the Mississippi River Valley, in 1834, the Quapaw were

removed to Indian Territory. In 1835,

the Caddo were removed to Texas (then Mexico), and in 1859 were relocated to

Indian Territory.

Indian removals from the Southeastern United States.

The

Seminole fought to defend their Florida peninsular homeland. A few bands reluctantly complied with the

Indian Removal Act, but most resisted violently, leading to a second Seminole

War (1835 - 1842). Most of the Seminole

population had been relocated to Indian Country or killed by the mid-1840s,

though several hundred settled in southwest Florida, where they were allowed to

remain in an uneasy truce. Tensions over the growth of nearby Fort Myers led to

renewed hostilities, and the Third Seminole War (1855 - 1858). By the cessation of active fighting, the few

remaining bands of Seminoles in Florida had fled deep into the Everglades to

land unwanted by white settlers. Taken together, the Seminole Wars were the

longest, most expensive, and most deadly of all American Indian Wars.

Native Peoples Today

Almost 200 years after Native

American tribes were removed from the Southeastern United States, they are

still located in Indian Territory, now the state of Oklahoma. This includes the tribes from the Lower

Mississippi Valley: the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Quapaw, and Caddo. The current Native American reservations in

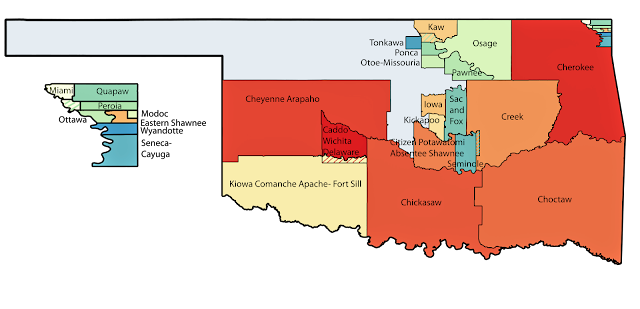

Oklahoma are shown in the figure below.

Note the additional tribes, from outside the Southeast, that were

relocated.

Native American nations relocated to reservations in Oklahoma.

There are currently 38 federally

recognized Indian nations located in the State of Oklahoma.

When the U.S. Government started to remove

Native Americans from the Southeast in the 1830s, it focused its efforts on Native peoples who

lived on land that was good for farming or rich in mineral resources.

The

government paid less attention to other groups, so some were able to avoid

removal and stay in the Southeast. For

example, in the Lower Mississippi River Valley today, the Choctaw have one small

reservation in central Louisiana, and a larger one in central Mississippi,

comprising eight communities; the Tunica have a small reservation in central

Louisiana; the Coushatta have a small reservation in southwest Louisiana; and

the Chitimacha have a small reservation near the south-central

coast of Louisiana.

Final

Notes

When Europeans first arrived in North America, approximately five

hundred sovereign Indian nations were prospering in what is now the United

States. Each nation possessed its own government, culture, and language.

The

oppressive and often brutal actions against Native Americans in the Southeast

occurred all across America, including Alaska, as the land-hungry United States

expanded across the continent. New diseases, wars, ethnic cleansing, and enslavement reduced

the Indian population from more than one million people at the time of Columbus

to about three hundred thousand in 1900.

Since then, the number of Native Americans has grown. In the 2020

U.S. Census, an estimated 3.7 million people identified as Native

American alone, accounting for 1.1% of all people living in the United States. An additional 5.9 million people identified as

Native American and one other race group. Together, these groups comprise

2.9% of the total U.S. population in 2020.

About 13 % of this group (1.3 million people) live on one of the current

324 federally-recognized Indian reservations or other trust lands. The

majority of Native Americans live outside the reservations, mainly in the

larger western cities such as Phoenix and Los Angeles.

Here are a few sobering statistics

from the 2020 U.S. Census:

The median household

income for Native Americans was $49,906, as compared to $71,664 for

non-Hispanic white households. 20.3 % of

this population lived at the poverty level, as compared to 9.0 % of

non-Hispanic whites. The overall

unemployment rate for Native Americas was 7.9 %, as compared to 3.7 % for non-Hispanic

whites.

It is significant to note

that Native Americans frequently contend with issues that prevent them from

receiving quality medical care. These

issues include cultural barriers, geographic isolation, inadequate sewage

disposal, and low income.

Comments

Post a Comment