HISTORY55 - North Central New Mexico

Pat and I will be automobile

touring in New Mexico this summer, and as usual, I wanted to study up on the

history or the area we will be visiting.

In previous blogs, I have written about the history of Albuquerque, New

Mexico (June 15, 2019) and the expansion of the Spanish Empire from Mexico into

New Mexico (August 3, 2020). This blog

will focus on the history of north central New Mexico.

After short introductions to New

Mexico and north central New Mexico, I will focus on the history of the towns

of Santa Fe, Taos, and Las Vegas.

My principal sources include “Northern

New Mexico History,” riograndeha.org; “New Mexico,” newworldenyclopedia.org;

“History: New Mexico’s Geography,” online.nmartmuseum.org; “Santa Fe, New

Mexico,” newworldencyclopedia.org; “Santa Fe History,” santafe.org; “Sangre de

Cristo Mountains,” “Santa Fe, New Mexico,” “Taos, New Mexico,” and “Las Vegas,

New Mexico,” Wikipedia; “Taos, New Mexico - Art, Architecture & History,”

legendsofamerica.com; “Taos History and Timeline,” taosacountyhistoricalsociety.org;

“Las Vegas, New Mexico,” takearoadtrip.com; “New Mexico’s ‘Other’ Las Vegas,”

historynet.com; and numerous other online sources.

Introduction to New Mexico

New

Mexico, known as the Land of Enchantment, is one of the Mountain States of the

southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region of the western U.S.

with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona, and bordered by Texas to the east and

southeast, Oklahoma to the northeast, and the Mexican states of Chihuahua and

Sonora to the south. New Mexico’s capital

is Santa Fe and the largest city is Albuquerque, with a 2022 metro area

population of 942,000.

New

Mexico is the fifth-largest of the fifty states, but with just over 2.1 million

residents, ranks 36th in population and 46th in

population density. Its climate and

geography are highly varied, ranging from forested mountains to sparse deserts;

the northern and eastern regions exhibit a colder alpine climate, while the

west and south are warmer and more arid; the Rio Grande and its fertile valley

run from north-to-south, creating a riparian climate through the center of the

state that supports a forest habitat and a semi-arid climate. One-third of New Mexico's land is federally

owned, and the state hosts many protected wilderness areas and national

monuments, including three UNESCO World Heritage Sites, the most of any state.

In prehistoric times, New Mexico was home to Ancestral

Puebloans in the north and the Mogollon in the south.

Around the year 900, northern New Mexico was populated by the modern Pueblo

peoples. Navajos and Apache migrated into New Mexico from the north towards the end of

the 15th century.

In 1540-1542, Spanish

Conquistador Francisco Vazquez de Coronado led a large expedition from Mexico,

north to present day Kansas, through northern Mexico. This was the first systematic exploration of

the American southwest by a European, and served as a springboard for subsequent

Spanish explorers and colonizers. In 1598, New Mexico became part of the Spanish

Viceroyalty of New Spain. In 1610, Santa

Fe became the capital of Spanish New Mexico.

In

1821, when Mexico achieved its independence from Spain, New Mexico became a

province of Mexico. Then in 1850,

following the Mexican-American War, New Mexico became a United States territory.

And finally in 1912, New Mexico became the

47th U.S. state.

As

a result of multinational occupation, the demographics and culture of New

Mexico are unique for their strong Amerindian, Spanish, and Mexican cultural

influences.

The figure below identifies the focus area for this blog: north central New Mexico – including the

towns of Santa Fe, Taos, and Las Vegas.

|

| Map of New Mexico with the north central area highlighted. |

The Landscape of North Central New Mexico

The north central section of New Mexico is covered by a series

of mountain ranges that are part of the Rocky Mountains. The Rio Grande River cuts through the Rocky

Mountains from north to south. East of

the Rio Grande, is the Sangre de Cristo (Blood of Christ) Mountain range, that

extends north-south from south central Colorado into north central New Mexico,

the southernmost of the subranges of the Rocky Mountains.

As

shown in the figure below, Santa Fe, Taos, and Las Vegas all lie in the

foothills of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains:

Santa Fe at the extreme southwest at an elevation of 7,199 feet; Taos in

the western foothills, at an elevation of 6,969 feet; and Las Vegas to the

southeast, at an elevation of 6,435 feet.

|

| Sangre de Cristo Mountains showing focus towns in the foothills. |

The Sangre de Cristo Mountains include the highest point in

New Mexico, Wheeler Peak, about 20 miles northeast of Taos, at 13,167 feet.

Santa Fe

Santa Fe is located at the foot of the Sangre de Cristo

Mountains, along the Santa Fe River, a tributary of the Rio Grande. Santa

Fe is the oldest capital city in United

States, the oldest European community west of the Mississippi, and the highest

state capital in the U.S. at 7,199 feet elevation.

Preconquest and Founding (circa 900 to 1610).

Santa

Fe's site was originally occupied by a number of Pueblo Indian villages with

founding dates from 900 to 1150. Most

archaeologists agree that these sites were abandoned 200 years before the

Spanish arrived. There is little

evidence of their remains in Santa Fe today.

In 1598, Juan de Onate came north from

Mexico with 500 settlers and soldiers to found the first Spanish settlement in

New Mexico at San Juan Pueblo, about 25 miles northwest of today’s Santa

Fe. That same year, the Province of New

Mexico was officially created by the King of Spain, with Juan de Onate named as

Governor.

San Juan proved to be vulnerable to

Indian attacks - probably Navajo, and in 1610, the settlement was moved to

Santa Fe, which was inhabited on a

very small scale in 1607, and truly settled by the conquistador Don Pedro de

Peralta in 1609-1610.

Santa

Fe (holy faith in Spanish) was formally

founded and made New Mexico’s capital in 1610. The oldest public building in America, the

Palace of the Governors, was built in 1610.

Over the years, Santa Fe expanded outward from the

Palace of the Governors as its central building.

Onate pioneered the “Royal Road,”

a 700-mile trail from Mexico City to his remote colony in Santa Fe.

|

| The Santa Fe Plaza and Palace of the Governors, 1885. |

Settlement, Revolt & Reconquest (1610 to 1692).

For

decades, Spanish soldiers and officials, as well as Franciscan missionaries,

sought to subjugate and convert the Pueblo Indians of northern New Mexico and

northeastern Arizona. The indigenous

population at the time was close to 100,000 people, who spoke nine basic

languages and lived in an estimated 70 multi-storied adobe towns (pueblos),

many of which still exist today. In

1680, Pueblo Indians revolted against the estimated 2,500 Spanish colonists in

New Mexico, killing 400 of them and driving the rest back into Mexico. The conquering Pueblos sacked Santa Fe, and

burned most of the buildings, except the Palace of the Governors.

Pueblo Indians occupied Santa Fe until 1692, when Don Diego de

Vargas reconquered the region after a bloodless siege. The Pueblo leaders

gathered in Santa Fe, met with De Vargas, and agreed to peace. The Spanish issued substantial land grants to

each pueblo and appointed a public defender to protect the rights of the Native

Americans and argue their legal cases in the Spanish courts.

Spanish Empire (1692 to 1821).

Santa

Fe grew and prospered under Spanish control. Spanish authorities and missionaries - under

pressure from constant raids by nomadic Indians and often bloody wars with the

Comanches, Apache, and Navajos, formed an alliance with Pueblo Indians and

maintained a successful religious and civil policy of peaceful coexistence. Following a policy of “economically closed

empire,” trade was disallowed with Americans, British, and French.

The Mexican Period (1821 to 1846). When

Mexico gained its independence from Spain, Santa Fe became the capital of the

province of New Mexico.

While change was

slow to come to remote New Mexico, one major effect was the opening of the

region for the first time to American trade. In 1822, William Becknell blazed the 1,000-mile-long Santa Fe

Trail between Independence Missouri and Santa Fe. The Santa Fe Trail brought American goods and merchants to New Mexico from

Missouri in ever-increasing numbers. Aggressive Yankee traders

used Santa Fe's Plaza as a stock corral.

Another important trade route was first established in 1829.

The Old Spanish Trail connected Santa Fe with Los Angeles, California. Approximately 700 miles long, the trail ran

through areas of high mountains, arid deserts, and deep canyons. It is considered one of the most arduous of

all trade routes ever established in the United States. The trail was extensively used by traders,

with pack trains, from about 1830 until the mid-1850s.

|

| The original route of the Old Spanish Trail opened in 1829, connecting Santa Fe to Los Angles, California. |

For a brief period in 1837, northern New Mexico farmers rebelled

against Mexican rule, killed the provincial governor in what has been called

the Chimayo Rebellion (named after a village north of Santa Fe) and occupied

the capital. The insurrectionists were

soon defeated, however.

American

Territorial Period (1846 to 1912). On August 18, 1846, in the early period of the

Mexican-American War, American army general, Stephen Watts Kearny captured

Santa Fe, and raised the American flag over the Plaza. At the end of the war, in 1848, Mexico signed

the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ceding vast southwestern lands, including

much of the future states of New Mexico, Arizona, and California to the United

States.

In 1850, the U.S. Congress established

the New Mexico Territory, which at that time included Arizona. Thirteen years later, during the American

Civil War, on February 24, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed the bill separating

Arizona as a separate territory.

For

a few days in March 1863, the Confederate flag of General Henry Sibley flew

over Santa Fe, until he was defeated by Union troops.

With

the arrival of the telegraph in 1868, and the coming of the Atchison, Topeka

and the Santa Fe Railroad in 1880, Santa Fe underwent economic growth. There were brief mining booms in the nearby mountains, but the

city essentially remained a trading center for ranchers, farmers, and Indians.

|

| The magnificent Roman Catholic Saint Francis Cathedral was built in 1869-1886 in downtown Santa Fe, on the site of an older church that was destroyed in 1680 Pueblo Revolt. |

Statehood (1912 to present). When

New Mexico gained statehood in 1912, many people were drawn to Santa Fe's dry

climate as a cure for tuberculosis. The

Museum of New Mexico had opened in 1909, and by 1917, its Museum of Fine Arts

was built. The state museum's emphasis

on local history and native culture did much to reinforce Santa Fe's image as

an "exotic" city.

Throughout

Santa Fe's long and varied history of conquest, the town has also been the

region's seat of culture and civilization. Inhabitants left a legacy of architecture and

city planning that today makes Santa Fe the most significant historic city in

the American West.

Santa

Fe has had an association with science and technology since 1943 when the town

served as the gateway to Los Alamos National Laboratory, where the first atomic

bomb was designed. (Today, Los Alamos is one of the

largest science and technology institutions in the world, conducting research

in national security, space exploration, nuclear fusion, renewable energy,

medicine, nanotechnology, and supercomputing.)

In 1984, the Santa Fe Institute was founded to

research complex systems in the physical, biological, economic, and political

sciences. The National Center for Genome

Resources was founded in 1994 to focus on research at the intersection among

bioscience, computing, and mathematics. In

the 1990s and 2000s several technology companies formed to commercialize

technologies from Santa Fe’s research labs.

A

large artistic community thrives in Santa Fe, with museums of Spanish colonial,

international folk, Navajo ceremonial, modern Native American, and other modern art. Another museum honors late resident Georgia

O'Keeffe, one of the most well-known New Mexico-based artists. Colonies for artists and writers thrive, and

the small city teems with art galleries. In August, the city hosts the annual Santa Fe

Indian Market, which is the oldest and largest juried Native American art

showcase in the world.

Performing

arts include the renowned Santa Fe Opera which presents five operas in

repertory each July to August, the Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival held each

summer, and the restored Lensic Theater a principal venue for many kinds of

performances.

Today,

Santa Fe has a population of about 86,000 people. After state government, tourism is a major aspect of the

Santa Fe economy, with visitors attracted year-round by the climate and related

outdoor activities, as well as the city's and region's cultural activities. Within

easy driving distance for day-trips is the historic town of Taos, about 70 miles

north and the historic Bandelier National Monument (preserves pueblo structures dating

between 1150 and 1600 AD) about 30miles to

the northwest. Santa Fe's ski area, Ski Santa

Fe, is about 16 miles north of the city.

|

| Modern map of downtown Santa Fe, New Mexico. |

Taos

The town of Taos is located in the western foothills of the

Sangre de Cristo Mountains, about 70 miles north of Santa Fe, at an elevation

of 6,969 feet. Taos Pueblo, occupied continuously

for nearly 1,000 years, is located about three miles northeast of town. The Rio Pueblos de Taos, a tributary of the

Rio Grande, from its source in the Sangre de Christo Mountains, flows through

Taos Pueblo and near the town of Taos. The town derives its name from the native Taos

language meaning “place of red willows.”

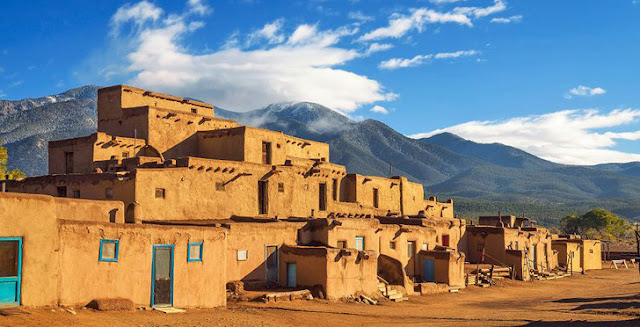

|

| Today’s Taos Pueblo and the Rio Pueblos de Taos. |

Preconquest

and Founding (circa 900 to 1540). The ancestors of the Pueblo

people, commonly known as the Anasazi, were the first

permanent inhabitants of Taos Valley.

Pit houses in the Taos area testify to their presence since AD 900. Around AD 1200, the Anasazi aggregated into

above-ground pueblos of 50-100 rooms.

The Taos Pueblo, that continues to stand today, was probably

built between AD 1200 and 1450. The Taos Pueblo is the most northern of the New Mexico pueblos. The pueblo was built of adobe, at some places

five stories high - a combination of many individual homes with common walls.

Throughout

its early years, Taos Pueblo was a central point of trade between the native

populations along the Rio Grande and far away neighbors. Eventually, trade routes would link Taos to

the northernmost towns of New Spain and Mexico’s cities via the “Royal Road”

trail through Santa Fe to Mexico City.

Settlement,

Revolt & Reconquest (1540 to 1696). The first European visitors to Taos Pueblo

arrived in 1540 as a small detachment from the Spanish Conquistador Francisco Vásquez de Coronado expedition, which stopped at

many of New Mexico’s pueblos searching for the rumored Seven

Cities of Gold.

The

first Spanish-influenced architecture appeared in Taos Pueblo after Fray

Francisco de Zamora came there in 1598 to establish a mission under orders from

Spanish Governor Don Juan de Oñate.

The

Spanish village of Taos was established in about 1615, following the Spanish

conquest of the local Indian Pueblo villages by Geneva Vigil. Initially, the relations of the Spanish

settlers with Taos Pueblo were amicable.

Still, resentment of meddling by missionaries and demands for a tribute

to the church and Spanish colonists, led to revolts in 1609, 1613, and 1640,

but, these small insurgencies did not stop the determined Spanish priests and

colonists.

Throughout

the 1600s, cultural tensions grew between the native populations of the Southwest and the increasing Spanish presence, leading to

the Pueblo Revolt of 1680.

Unlike

other New Mexico pueblos, after the Spanish Reconquest in 1692, the Taos Pueblo

continued armed resistance against the Spanish until 1696, when Governor Diego

de Vargas defeated the Indians at Taos Canyon.

Spanish Empire (1696 to 1821).

The Spanish brought modern methods for irrigation called

acequias, and introduced fruit and vegetables to the region. They also introduced livestock. The Puebloans taught the Spanish how to build

adobe structures.

In 1723, the Spanish government forbade trade

with the French, but allowed limited trade with the Plains Tribes, thereby

giving rise to the annual summer trade fairs in Taos, where Comanche, Kiowa, and others came

in great numbers to trade captives for horses, grain and trade goods from

Mexico.

In 1772, the Franciscans supervised the

construction of the historic San Francisco de Assisi Mission Church that was

finally completed in 1816, about five miles south of the Taos Plaza.

|

| The San Francisco de Assisi Mission Church in Taos still serves a congregation today. |

In 1776, at the time of the American Declaration of Independence, there were an estimated 67

families, with 306 Spaniards in the Taos area.

During the 1770s, Taos was repeatedly raided

by Comanche, who then lived on the plains of what is now eastern Colorado. Juan

Bautista de Anza, governor of the Province of New Mexico, led a successful

punitive expedition in 1779 against the Comanche.

The town of Taos was only intermittently occupied until its formal

establishment in 1795 by Nuevo México Governor Fernando Chacón to act as

fortified plaza and trading outpost for the neighboring Taos

Pueblo and

Spanish communities.

Between 1796 and 1797, the Don Fernando de

Taos Land Grant gave land to 63 Spanish families in the Taos valley.

Mexican Period (1821-1848). Mexican Independence from Spain

in 1821 was hardly noticed in Taos, but the trickle of Anglo newcomers from the

East became a floodtide after the opening of the Santa Fe Trail in 1822.

In 1826, a

sixteen-year-old runaway apprentice named Christopher (Kit) Carson arrived in

Taos from Missouri with a group of traders.

In 1843, the famous frontiersman married local Mexican, Josefa Jaramillo. Carson purchased a house from the Jaramillo

family as a wedding present to his new bride.

The house built in 1825, served as the Carson’s home until 1868, and

today as the Kit Carson Home and Museum.

In 1834-35, the first

printing press west of the Mississippi River was brought to Taos by Padre

António José Martínez, assigned to the parish of Guadalupe at Taos. Martinez then published the first newspaper

"El Crepusculo" which was the predecessor to The Taos News.

American Territorial Period (1847

to 1912). New

Mexico formally became a territory of the United States with the signing of the

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1847, ending the Mexican-American War. However, many of the native Mexicans and

Indians were not happy with this event.

The Mexicans in the Taos area resented the newcomers and enlisted the

Taos Indians to aid them in an insurrection.

Charles

Bent, the new American governor, who was headquartered at Taos, was killed and

scalped in January 1847, along with many other American officials and

residents. The rebels then marched on

Santa Fe, but the response of the American Army was immediate. A force of more than 300 soldiers from Santa

Fe and Albuquerque quickly rode to Taos and the rebels were soundly defeated. After a trial, several

vanquished rebels convicted of crimes related to the uprising were then

sentenced and hung at the Taos Plaza.

In 1848, Taos was

connected to the Old Spanish Trail, and thus could be directly involved in

trade with southern California.

Taos

Valley flourished during this period as other cultures found their way into the

territory. There were dozens of French,

American, and Canadian trappers. A brisk

fur trade began, bringing yet another element - the

mountain men - to the Taos trade fair.

By that time, the Taos Valley was well populated with livestock,

agriculture, and people who supplied Mexico with inexpensive goods.

In 1872, the Río del

Norte and Santa Fe Railroad was incorporated in Taos, but the proposed line - from

Costilla, north of Taos near the border with Colorado, through Taos, and on to

Santa Fe, was never surveyed. Later

attempts to bring rail service to Taos also failed, and Taos remains somewhat

isolated today, distant from many of the stresses of development.

The

1870s brought a different type of newcomer to the Taos Valley, when gold and

rumors of gold, silver, and copper spread throughout the region. Miners began searching for gold in the Red

River area, about 30 miles northeast of Taos in the Sangre de Christo

Mountains. The fever spread, and from

1880 to 1895, the Rio Hondo, near what is now Taos Ski Valley, was actively

searched by placer miners. Mining,

however, was not productive in the Taos area.

In

1898, two young American artists from the East, named Ernest Blumenschein and

Bert Phillips, discovered the valley after their wagon broke down north of

Taos. They decided to stay, captivated

by the beauty of the area. As word of

their discovery spread throughout the art community, they were joined by other

associates. This was the start of Taos’

history and reputation as an artist’s community.

Statehood

(1912 to present). Three years after New Mexico became a state,

in 1915, the Taos Society of Artists was formed, which unwittingly helped found

one of Taos’ leading sources of revenue in the 20th century - the

tourist trade.

In

1917, socialite Mabel Dodge Luhan arrived and eventually brought to Taos

creative luminaries such as Ansel Adams, Willa Cather, Aldous Huxley, Carl

Jung, D.H. Lawrence, Georgia O’Keeffe, Thornton Wilder, and Thomas Wolfe.

On

May 9, 1932, the Taos County Courthouse and the other buildings on the north

side of the Plaza were destroyed by the first of a series of fires in the early

1930s. This led to the incorporation of

the Town of Taos on May 7, 1934, and the establishment of a fire department and

public water system.

In

1956, the Taos Ski Valley was established, bringing more tourism to the

valley. Before long, other area ski

resorts also sprang up nearby - Red River, Sipapu, and Angel Fire.

In

1965, the (then) second-highest suspension bridge (about 600 feet above the Rio

Grande) in the U.S. highway system was built spanning the Rio Grande Gorge,

along US Highway 64, heading northward to Colorado. Today, the bridge is tenth highest in the

U.S.

|

| The Rio Grande Gorge Bridge. |

During

the 1960s and 1970s, the Taos area was a

mecca for the Hippie movement, where the young Counter Culture dreamed of

building a better world. Taos became

known as the Hippie Capital of the U.S.

Today, Taos is a mecca for

tourists and retirees. The largest

industries in Taos are retail trade, health care and social assistance, and

other services. Four

miles south of Taos Is the center of fertile agricultural and fruit lands.

There

are three art museums in Taos: Harwood Museum of Art, Taos Art Museum and Millicent

Rogers Museum that provide art from the Pueblo Native Americans, Taos Society

of Artists, and modern and contemporary artists of the Taos art colony. The town has more than 80 art galleries, and

there are several houses of the Taos Society of Artists.

|

| Downtown Taos against the Sangre de Christo Mountains. |

There

are several local venues for the performing arts in Taos. The Taos Center for

the Arts (TCA) draws nationally renowned and local performers at the Taos

Community Auditorium. Three chamber

music groups perform at TCA:

The

Carson National Forest and Rio Grande del Norte National Monument provide

many opportunities for recreation, such as hiking, skiing, fly fishing,

horseback riding, golfing, hot air ballooning, rafting, and mountain biking.

In

the winter, many people come to Taos to ski in the mountains. Other winter activities include hot air

ballooning, horseback riding, snow-shoeing, cross-country skiing, ski skating,

ice skating, ice fishing, and snowmobiling.

Taos

is known worldwide by artists, outdoor enthusiasts, and historians. The small town, of about six square miles and

5,866 people, incorporates three cultures - Native American,

Hispanic, and Anglo - into a beautiful city with a heritage of colorful people. Taos is home to more than twenty sites on the National Register of Historic Places.

The

Taos Pueblo today occupies a fertile tract of about 15.6 square miles. There are over 1,900 people in the Taos

Pueblo community, though many modern homes are nearby. There are about 150 people who live at the

pueblo year-round. The Taos Pueblo was

added as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1992.

|

| Modern map of Taos, New Mexico. |

Las Vegas

Las

Vegas is located 65 miles east of Santa Fe.

Once two separate municipalities, both named Las Vegas, separated by the

Gallinas River, the town is now unified with 7.5 square miles of total land area. Unlike Santa Fe and Taos, whose Anglo origins

reach back to the end of the 16th century, Las Vegas, New Mexico was

founded early in the 19th century.

Mexican Period (1821-1846). In 1835, 29 Spanish settlers obtained a land

grant from the Mexican government for a new settlement on the western banks of

the Gallinas River. The Gallinas River provided a fertile valley

for agriculture and critical water for irrigating crops.

The settlers named their village

Nuestra Señora de los Dolores de las Vegas Grandes (Our Lady of Sorrows of the

Great Meadows). The location had long

been a crossroad between the nomadic Plains Indians and the Pueblo peoples of

the Rio Grande Valley.

The

settlement was laid out in the traditional Spanish Colonial style, with a central

plaza surrounded by buildings which could serve as fortifications in case of

attack. Besides the plaza, there were dwellings,

farmlands watered by an irrigation ditch, and communal lands for grazing sheep.

The

new town of Las Vegas soon prospered as a main stopping place for traders

heading west on the Santa Fe Trail, that had opened in 1822. When the caravans arrived in the Las Vegas

Plaza, church bells rang and carts of the townspeople were set up in the plaza

to supply the traders with food, wood, and other goods. It was a sort of

farmer's market.

American Territorial Period

(1846-1912). When the Mexican-American

War started in 1846, Las Vegas was the first New Mexican town marched upon by the Army of West, led by General Stephen Kearny. Kearny delivered an address at the Plaza of

Las Vegas claiming New Mexico for the United States. With that pronouncement, the “Mexican town”

assumed a new identity - that of an American frontier town during New Mexico’s

long and boisterous territorial era.

In

1847, Las Vegas was the site of the Battle of Las Vega, which was a part of the broader Taos Revolt by local Hispanos and Pueblo peoples against occupying United States

forces.

In

1851, Fort Union was established 18 miles north of Las Vegas for the protection

of the wagon caravans on the Santa Fe Trail from Indian raids. Because of the fort’s presence, towns along

the trail were allowed to prosper, many supplying the fort with food. Beef

and timber were also sold to the fort, which enriched the town of Las Vegas.

By

the 1860s, Las Vegas was the leading commercial center for New Mexico and home

to merchants of many nationalities including German Jews and French Canadians. Textiles,

furniture, whiskey, metal tools, and tobacco could be bought cheaper from the

U.S. than from Mexico, and sold in the merchant establishments of Las Vegas.

The

Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad arrived at Las Vegas from the north on

July 4, 1879. To maintain control of development rights, the

railroad established a station and related development one mile east of the

Plaza on the other side of the Gallinas River, creating a separate, rival New

Town, as occurred elsewhere in the Old West.

Now there were two communities named Las Vegas - old and new, west

and east, Mexican and Anglo - creating a rift that was to persist for almost a

century. (The same competing railroad-arrival development

occurred in Albuquerque.)

During the railroad era Las Vegas

boomed, quickly becoming one of the largest cities in the American Southwest,

the largest city in New Mexico by 1900.

Unlike the roads that meandered around

the Plaza on the older west side, a neat grid of streets laid out in straight

lines distinguished the newer East Las Vegas.

The newcomers constructed grandiose Victorian buildings that contrasted

with the earlier, earthy adobes. Anglos

crossed the bridge to build on both sides of the river, so that even today the

elegant three-story Plaza Hotel, dating from 1882, abuts rough-hewn adobes

facing the Old Town Plaza.

Along with a renewed surge in

prosperity, the arrival of the railroad brought a period of lawlessness that

served as the fodder for many a Wild West tale.

Murderers,

robbers, thieves, gamblers, gunmen, swindlers, vagrants, and tramps poured in,

transforming the eastern side of the settlement into a virtually lawless

brawl. Saloons and dance halls multiplied,

catering to gunslingers, gamblers, and shady operators of every stripe. This was the period when Wyatt Earp’s pal Doc

Holliday operated a saloon (until he left town just ahead of a lynching party)

and Billy the Kid escaped from the Las Vegas jail.

In one month in 1880, 29 men met a

violent death - some were hanged from the windmill that stood in the center of

the Plaza. Outraged citizens recruited

the so-called “peace officers” known as the Dodge City Gang, but the stagecoach

and train robberies continued, with the perpetrators often shielded by corrupt

lawmen.

Meanwhile, Anglo cattle ranchers,

their herds increasing exponentially, began encroaching on Las Vegas’ communal

lands. From 1889 to 1892, night-riding

residents called “Gorras

Blancas” (White Hats) protested the intrusion into their pasturelands

by cutting fences and burning barns. The

cattle wars provided cover for local saloon owner Vicente Silva and his Society

of Bandits to engage in large-scale cattle-rustling.

In

1890, Fort Union was closed by the War Department in its goal to abandon all

frontier posts.

Toward the end of the century, the

trains brought wealthy vacationers to the Southwest, and luxury hotels sprang

up in Las Vegas to host them. The Plaza

Hotel, built in 1882, and dubbed “The Belle of the Southwest,” has been fully

restored and is today open for business, presiding regally over the Old Town

Plaza. Built as a destination hotel in

1886 by the railroad, the Queen Anne structure, 90,000-square-foot, 400

room

Montezuma Castle hotel was considered one of the places to visit at the turn of

the century. Restored in 1981, today the

building houses multiple college facilities.

One of the most stylish luxury hotels, the Mission Revival-style La

Castañeda, was built in 1898 as one of Fred Harvey’s railroad hotels. The 25,000-square-foot hotel had about 40 guest rooms, a 108-seat dining

room, and a 51-seat lunch counter. The La Castañeda

Hotel has been fully restored, and reopened in 2019.

|

| The Plaza Hotel today. |

|

| The Castañeda Hotel today. |

Besides

luxury hotels, turn-of-the-century Las Vegas featured all the modern amenities,

including an electric street railway, the Duncan Opera House, a Carnegie

library, and the New Mexico Normal School (now New Mexico Highlands

University).

|

| Las Vegas in the early 1900s. |

Statehood

(1912 to present). Beginning in 1915, the Las Vegas Cowboys'

Reunions were held annually until 1931; then in 1939, the Cowboys' Reunions

were re-established. These reunions were

organized by a group of ranching families and cowboys, which soon became the

Las Vegas Cowboys' Reunion Association.

The Reunions celebrated ranching life, which began in northern New Mexico

in the early 1800s, and continues into the 21st century. The Cowboys' Reunions reflect the occupations

of the area and attract huge crowds for their four days of events

As the rail system spread, commerce on

the Santa Fe Trail declined. Moreover,

other railroad cities, like Albuquerque to the southwest, claimed their share

of rail-generated profits, so that Las Vegas gradually sank into obscurity.

Since

the decline and restructuring of the railroad industry, beginning in the 1950s,

Las Vegas’ population has remained relatively constant.

Finally, in 1970, police, fire and

other government departments from East and West Las Vegas came together to form

one city. Although Old Town and New Town

have been combined, separate school districts have been maintained.

In the 20th century, as Las

Vegas slid into a long economic decline, the 19thcentury buildings

remained standing. The upshot is the

town’s surprisingly hefty inventory of 918 buildings on the National Register

of Historic Places, which has gained Las Vegas, a spot on the National

Register’s list of “Distinctive Destinations.”

The

2020 population of Las Vegas, New Mexico was 13,055, gradually declining from

13,753 in 2010.

|

| Las Vegas today. |

|

| Modern map of Las Vegas, New Mexico. |

Pat and I can’t wait to visit north central New Mexico!

Comments

Post a Comment