HISTORY46 - Pathways of Arizona History

This is an article about Arizona’s early explorers and the pathways they blazed - pathways that opened up Arizona to the world and eventually established important transportation routes that enabled the complete development of the state.

The story starts in the 16th

century, with Spanish Conquistadors, looking for gold and follows history

through almost 300 years of Spanish presence, the birth and expansion of the

United States into the southwest, Mexican independence, the Mexican-American

War, and finally American exploration.

The story concludes with a snapshot of the legacy these pathfinders

provided for Arizona.

My primary resource for this

article was: Historical Atlas of Arizona, by Henry P. Walker and Don

Bufkin - particularly the fabulous maps.

I also used numerous online sources.

A note about my approach: I tried to put the various periods of

Arizona’s exploration into historical context - thus providing some historical

background before going through the various exploration maps. For reference purposes, most maps show

outlines of today’s U.S. states - sometimes before they actually became states. I generally refer to “Arizona” and “New

Mexico” as the lands included in the current states, ignoring the period when

they were combined in the New Mexico Territory.

Spanish Explorers of Arizona

In 1492, forty-four years before

the Spanish set foot in Arizona, Christopher Columbus, sailing across the

Atlantic Ocean from Spain, made landfall on San Salvador Island in the Bahamas.

After 27 years of exploration and

settlement on islands in the Caribbean Sea, and exploration along the coasts of

North and South America, in 1519, Spanish Conquistador Hernán Cortés landed on

the coast of the modern-day Mexican state of Veracruz, to conquer the

indigenous Aztecs and reap the spoils of their magnificent capital of

Tenochtitlán. Following the fall of the

Aztecs in 1521, Spain established the Viceroyalty of New Spain, an entity of

the worldwide Spanish Empire, with its capital in Mexico City on the

obliterated site of Tenochtitlán. New

Spain continued to grow to the south, as the Spanish conquered the rest of southern

Mexico and Central America. By the

1530s, the Spanish began looking north in the hope of discovering new wealthy

civilizations to conquer, precious metals to mine, and indigenous peoples to

convert to Christianity.

Please refer to the map below for

the discussion of Spanish explorers of Arizona.

Routes of Spanish explorers of Arizona from 1536 to 1776.

Possibly the first Spanish

penetration into Arizona was that of Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca and three

companions, who had been shipwrecked on the Texas coast in 1528, and after six

years of servitude among coastal Indians, made their escape. On foot they crossed Texas and New Mexico,

and swung through the southeastern corner of Arizona, before reaching Culiacan

in northwestern Mexico. As a result of

Cabeza de Vaca’s stories of vast riches to the north, the Viceroy of New Spain

sent Franciscan Friar Marcos de Niza, with Esteban the Moor, one of Cabeza’s

companions, to check out the tales.

Esteban, going in advance, was killed at a Native American Zuni village,

and Marcos de Niza returned south to Mexico.

Note: For more information on early Arizona Native

American cultures, see “History of Native Americans in Arizona,” in my online

book, Arizona Reflections - Living History from the Grand Canyon State

at: ringbrothershistory.com/bobsprojects/2015writings/July%2011%20AR%20Electronic%20Book.pdf.

In 1540, the reports of Friar

Marcos, added to those of Cabeza de Vaca, caused the Viceroy to send out an

expedition commanded by Francisco Vasquez de Coronado. Marching north from Culiacan, the army

entered Arizona via the San Pedro Valley, crossed the Mogollon Rim, and marched

up the Zuni River to the westernmost Zuni pueblo. From there, Coronado sent out exploring

parties: Captain Pedro de Tovar led a

small group to visit the Moqui (Hopi) villages to the west. Garcia Lopez de Cardenas was sent to investigate

“a great river” (Colorado River) further west, and the Spanish became the first

white men to see the Grand Canyon.

Coronado, with the main force, continued to the northeast, all the way

to the future state of Kansas.

Coronado arrives at a Zuni pueblo in 1540

Meanwhile, Hernando de Alarcon

took a group of ships from the Mexico’s west coast, up the Sea of Cortez, to

bring stores and provisions to resupply Coronado’s expedition near the mouth of

the Colorado River. The meeting with

Coronado never happened; Alarcon left letters at the planned rendezvous site,

which were found later that year by another Spanish explorer Melchior

Diaz. Alarcon was the first European to

ascend the Colorado River far enough to make important observations. (On a later voyage he probably proceeded past

the present-day site of Yuma, Arizona, upriver about 75 miles from the Sea of Cortez.)

After two years in America,

Coronado finally returned to Mexico on the same route he had used going north -

having found no gold or riches.

Note: These many years later, it’s difficult to

understand the logistical planning (expectations?) of Coronado’s expedition.

The Spanish didn’t return to

Arizona for four decades. In 1581, the

Spanish established an outpost in north-central New Mexico. In 1583, Don Antonio de Espejo, led an

expedition westward from New Mexico in search of mineral wealth. He visited the Zuni and Hopi villages in

Arizona, heard stories of silver mines further west, and continued searching

(without success) for them, probably reaching the Verde Valley.

In 1598, Juan de Onate came north

from Mexico with 500 settlers and soldiers to found the first Spanish

settlement in New Mexico at San Juan Pueblo, about 10 miles north of Taos. (The

settlement was moved to Santa Fe in 1609.)

Also in 1598, Onate visited the Zuni and Hopi pueblos to the west and

sent Farfan de los Godos to explore territory further southwest. Farfan staked out claims on mines near

present day Jerome, Arizona. Onate

accomplished the most extensive exploration of Arizona in the 17th

century, when in 1604-1605, marching west from New Mexico, he reached the

Colorado River and followed it downstream to the Sea of Cortez.

Franciscan missionaries had

accompanied Onate to New Mexico and began an 80-year period of mission building

at over 20 native pueblos across northern New Mexico, plus three missions as

far west as the Hopi pueblos in northeastern

Arizona. But the Spanish exploited

indigenous labor for transport, sold native slaves in New Spain, and sold goods

produced by slaves. Moreover, the

Franciscans tried to totally eliminate native religious practices- efforts that

included imprisonment, execution, and destroying religious articles.

Finally in 1680, the pueblo

people accomplished a well-coordinated revolt, driving the Spanish from

northeastern Arizona and all but the southern portion of New Mexico. It wasn’t until 1692,

that Diego de Vargas led Spanish forces

to a reconquest of the territory.

The first Spanish explorer to

leave a moderately accurate record of his travels was the Jesuit missionary

Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, who had been trained as a mathematician and a

cartographer. In 1687, Kino arrived in today’s

Mexican state of Sonora, and began to establish missions in northern Sonora,

and by 1691, in today’s southeastern Arizona.

Before his death in 1711, Kino would establish over 20 missions,

including several along the Santa Cruz River in Arizona, among the generally

peaceful indigenous Pima and Tohono O’odham peoples.

Kino traveled extensively in the southern

Arizona lands bounded by the San Pedro and Gila Rivers (called the

Papagueria). Based on these trips, he

prepared maps that showed most the Native American settlements.

Father Kino also explored the

lower Colorado River delta region. In

1700-1701, traveling from Caborca in northern Mexico, he followed the (now

historic) El Camino del Diablo (Devils Highway) Trail across the Sonoran Desert

to the Colorado River. Kino was the first

European to travel extensively throughout this desolate region in his quest to

prove that California was part of the North American mainland and not an island,

as was then commonly believed by world geographers.

Father Eusebio Kino established 20 missions in Sonora and southeastern Arizona, traveled extensively in the Sonoran Desert, and was the first Spanish explorer who left a records of his travels.

Spanish settlement of southeastern

Arizona began in the late 1690s, with a small cattle ranch near today’s

Mexico-U.S. border at the headwaters of the Santa Cruz River. Additional settlers followed, attracted by

the fertile Santa Cruz River Valley and silver mining interests.

In 1752, the Spanish built a presidio at

Tubac to protect Spanish interests in the Santa Cruz River Valley. In 1775, the Spanish moved the garrison to

the new site of Tucson.

During this period of presidio building and relocation, Juan Bautista

de Anza, Spanish Captain of the Tubac Presidio, and later to be the Governor of

New Mexico, made two trips to California. In 1774, the Spanish Viceroy sent Anza from

Tubac, along the Camino del Diablo Trail to Yuma, and on to Mission San Gabriel

near present day Los Angeles. The

following year. in 1775, Anza led a colony of settlers along the Santa Cruz and

Gila Rivers to Yuma and on to northern California, bringing settlers to California’s Monterey

presidio, exploring San Francisco Bay for future settlement, and establishing an

overland route to the Pacific Coast that would be followed by many travelers to

California in the future.

Traveling with Anza on both trips, was

Franciscan missionary Francisco Garces.

Returning from California in 1774, Garces left the party and traveled

into northern Arizona to visit the Yavapai people. On the 1775 trip, Garces crossed the

Colorado River near present day Needles, California, and traveled east to visit

the Hopi town of Oraibi, before returning to southeastern Arizona by way of the

Colorado and Gila Rivers.

The

final Spanish exploration of Arizona was in 1776, when Franciscan priests

Silvestre Velez de Escalante and Francisco Atanasio Dominguez attempted to open

a land route between Santa Fe and California.

They traveled north from Santa Fe, through western Colorado, then west

through northern Utah towards California.

The land was harsh and unforgiving, and hardships

encountered during travel forced the group to return to Santa Fe through

northern Arizona without reaching California.

They crossed the Colorado River

at Vada de los Padres in southern Utah. Maps and

documentation produced by the expedition aided future travelers. The Domínguez-Escalante route eventually

became the Old Spanish Trail, a trade route from Santa Fe to Pacific Coast

settlements, that was used from about 1830 to the mid-1850s.

The circuitous route of the Dominguez-Escalante expedition in 1776.

American Paths of the Mexican

War

A lot happened in America between 1776

and the start of the Mexican-American War in 1846. British America declared its independence,

fought the Revolutionary War, formed the United States of America from 13

colonies along the East Coast, and then quickly claimed land west to the

Mississippi River. The U.S. grew steadily,

buying the Louisiana Territory from France in 1804, receiving Florida from

Spain in 1819, annexing Texas from Mexico in 1845, and negotiating the Oregon

Territory from Great Britain in 1846.

The territory of the United States in 1846.

Meanwhile, after 300 years under

Spanish rule, Mexico declared its independence from Spain, fought a war to

secure it, and in 1821, became the Republic of Mexico, obtaining substantial,

formerly-Spanish lands in southwestern America, including the future U.S. state

of California.

Mexico inherited 19 Spanish missions and five protective presidios

in California. Large land grants

encouraged settlement and establishment of California Ranchos centered on cattle-raising. Neither Spain nor Mexico ever colonized areas beyond the

southern and central coastal areas of present-day California. Most interior areas, such as the Central

Valley and the deserts of California, remained in de facto

possession of indigenous peoples until the early 1840s, when more

inland land grants were made, and overland immigrants from the United

States began to settle inland areas. In

1846, there were a few American immigrants at the Pueblo of Monterey and the

Mexican Sonoma Barracks garrison near the future site of San Francisco.

During this period in southeastern

Arizona, mining, ranching, and missions prospered, but were almost constantly

under attack from native Apache. There

were virtually no Spanish or Mexican settlements in the rest of the future

state of Arizona. The total Mexican

population in Arizona in 1846 was probably well under 5,000 people.

The first reported penetrations

of Arizona by Anglo-Americans were those of fur traders in the 1820s, after

Mexican independence. These mountain men

travelled all over Arizona, trapping along major rivers. The 1830s, saw a few informal explorations of

potential east west trade routes across Arizona. These activities produced a lot of knowledge

of Arizona geography, stored away in the heads of a few people, but little, if

any, of it, was written down. It was

from this body of knowledgeable from mountain men that U.S. Army surveyors and

engineers would later obtain the guides they needed to show them trails and

water holes - such men as Kit Carson, Antoine Robidoux.

The Mexican-American War in

1846-1848 followed the U.S. annexation of Texas, which Mexico considered

Mexican territory. The U.S. quickly smothered Mexico with superior force, launching an

invasion of northern Mexico, while simultaneously invading New Mexico and

California, and blockading both of Mexico’s coasts. By terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo,

ending the war, the U.S. secured

all of today’s California; Nevada; and Utah; most of Arizona, down to the Gila

River; roughly half of New Mexico; and parts of Colorado and Wyoming.

Please refer to the map below for

the discussion of Arizona pathways of the Mexican War.

These Arizona pathways were established during the Mexican War.

When the war with Mexico broke

out in 1846, a small U.S. military force, designated as the Army of the West, was

collected at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas under the command of General Stephen

Kearny. The mission of this force was to

conquer New Mexico and California, and establish United States control over the

vast area of the American southwest.

Following the bloodless conquest

of New Mexico, Kearny marched south from Santa Fe along the Rio Grande

River. With Lieutenant Christopher “Kit”

Carson as guide, Kearny crossed southwestern New Mexico to the headwaters of

the Gila River, followed that stream down to its junction with the Colorado

River, and passed into California. The

conquest of California was accomplished after several months of fighting,

before a permanent peace was secured.

Kearny had with him Lieutenant

William H. Emory of the Corps of Topographical Engineers, whose map of the

route of the march was the first relatively accurate map of the Gila Trail, which

in few years would carry thousands of gold seekers to California.

Reinforcements for the Army of

the West left Fort Leavenworth about a month after Kearny’s departure. The force included volunteers from among

Mormons who were then moving westward from Nauvoo, Illinois, to eventual

settlement in Utah. Captain Philip St.

George Cooke was placed in command of the “Mormon Battalion,” ordered to march

to California, and to build a wagon road as he went.

Cooke followed Kearny’s route to

a point near the Burro Mountains in southwestern New Mexico. Here, because of the extremely rough going on

the upper Gila River, which was impractical for wagons, he changed his

direction of march from west to south-southwest, and entered present-day

Arizona through Guadalupe Pass in the Peloncillo Mountains. Reaching the San Pedro River, just south of

the present international boundary, the battalion marched north along the river

to about the site of Benson, and then swung westward to Tucson. After a short pause to obtain supplies, the

battalion marched northwest to the Pima Villages on the Gila River. From that point on, Cooke followed Kearney’s

route into California.

In 1848, after the peace treaty

ending the war with Mexico, a battalion of dragoons, commanded by Major

Lawrence Pike Graham, was ordered from Chihuahua, Mexico to California. Marching south of the present border, via

Janos and the presidio of Fronteras, the battalion reached the Santa Cruz River

and marched northward down the river to Tucson.

From there, they followed Cooke’s route to California.

American Explorers and

Surveyors

From the early 1840s to the

1860s, American explorers and surveyors were active in Arizona. Following the War with Mexico, and discovery

of gold in California, soon after in 1848, gold seekers from the East started

crossing Arizona by the thousands in 1849, on their way to California. Americans began settling around Yuma in

1851. By 1854, Americans had surveyed

feasible northern and southern Arizona routes for a transcontinental railroad,

but the southern route was south of the Gila River, in territory still

belonging to Mexico. So, later in 1854,

seeking to acquire land for a southern route of a future transcontinental

railroad, the U.S., with the Gadsden Purchase, bought land south of the Gila

River from Mexico. The U.S. then quickly

sent surveyors to Arizona to establish the new international boundary with

Mexico - as was done after the War with Mexico.

The Colorado River continued to be explored and finally, in the late

1860s, following the U.S. Civil War, the extreme northwestern part of Arizona

was explored.

Please refer to the map below for

the discussion of American explorers and surveyors.

Routes of American explorers and surveyors, 1844-1869.

The opening of the American West began in 1804, when the Lewis and Clark Expedition started exploration of the new Louisiana Purchase territory, followed in 1806 by Zebulon Pike’s exploration of Colorado. John C. Freemont (later to be the fifth Governor of the Arizona Territory) carried on this tradition of Western overland exploration with five expeditions between 1842-1854, making the American West accessible for many Americans. The second expedition (!844) crossed the extreme northwest corner of Arizona on the Old Spanish Trail

During the Gold Rush of 1849,

many parties of emigrants used the cross-Arizona southern overland trail

surveyed by William H. Emory with the Kearny Expedition in 1846. Through eastern Arizona, gold seekers

followed either the Cooke or Graham trails, established during the War with

Mexico. The entire route became known as

the historic Gila Trail.

In the 1850s and 1860s, the

Colorado River became the most important supply line for western Arizona. Under the Treaty of Guadalupe ending the War

with Mexico, American vessels could ply the Colorado River without interference

from Mexican authorities. Goods were

brought on ocean-going ships to Robinson’s Landing, near the mouth of the

Colorado River, and were transferred to shallow-draft river steamers. Yuma was settled in 1851, and Fort Yuma was

built that same year to defend the newly settled community, and southern

emigrant travelers, from local Quechan and Yuman Native Americans. After the Gadsden Purchase in 1854, Yuma

became the chief supply port from which supplies were hauled by wagon to all of

Arizona south of the Gila and Salt Rivers.

Meanwhile in northeastern

Arizona, the indigenous Navajos were opposing New Mexican settler encroachment on

their land. In 1849, topographical

engineer Lieutenant James H. Simpson accompanied a military expedition against

the Navajos in Canyon de Chelly. Based

on interviews with mountain men, Simpson reported that a wagon road west from

Zuni to California was feasible. In

1851, at the same time that Fort Defiance was established to create a presence

in Navajo territory, Captain Lorenzo Sitgreaves, of the Army Corps of

Engineers, was sent to seek out a route for the road and to explore the large

rivers in the newly acquired lands.

Sitgreaves’ work produced a careful study of a hitherto unknown area.

Because of the great interest in

possible routes for a transcontinental railroad, in 1853, Lieutenant Amiel W.

Whipple surveyed a path along the thirty-fifth parallel from Fort Smith

Arkansas to Los Angeles, California.

Whipple’s final report concluded that a possible railroad route lay

across the northern part of Arizona. (With

the thought that a wagon road might be converted into a railroad line, in

1857-1860, Edward F. Beale built a wagon road generally along the line [not identified

on above map] surveyed by Whipple.)

While Whipple was making his way

across northern Arizona, in 1854, prior to the Gadsden Purchase, Andrew B. Gray

was hired by the Texas Western Railroad to run a preliminary survey across

Mexican territory south of the Gila River.

It was realized in Washington

that more information was needed on the railroad possibilities of the southern

route. Lieutenant John G. Parke, in 1854,

with the permission of the Mexican Government, resurveyed the area between the

Pima Villages and the Rio Grande. His

route took him through Tucson and Apache Pass in the Chiricahua Mountains to a

junction with Cooke’s Wagon Road in New Mexico.

A year later, Parke again covered the route, and found a pass between

the base of Mount Graham and the Chiricahuas that cut thirty miles from the

distance and reduced the number of summits to be crossed.

With the additional lands added

to Arizona with the Gadsden Purchase, in 1855, William H. Emory led the

expedition, assisted by Lieutenant Nathaniel Michler, that surveyed the new

southern international boundary with Mexico.

(In 1852, John Russell Bartlett had finalized the survey of the international

border after the War with Mexico).

By 1858, the Colorado River was

the last major stream in the United States still to be explored. Steamers were already running from the

river’s mouth to Fort Yuma, when the army sent Lieutenant Joseph C. Ives to

determine how far north the river was navigable. (The practical head of navigation was about 300

miles north, but in seasons of high water, steamers could reach 100 miles

further, just before the river flowed out of the Grand Canyon.) After steaming as far north as he could, Ives

divided his party. Half returned

down-river on the steamer, and Ives took the other half overland, all the way

across Arizona, to Fort Defiance. The

reports of explorations provided a great amount of knowledge about the

geography, geology, plant and animal life, and Native Americans.

Because of the Civil War

(1861-1865), it was not until 1869 that another government-sponsored exploring

party entered Arizona. By this time,

only the extreme northwestern part of Arizona was still marked “unexplored” on

maps. In 1869, Major John W. Powell

descended the Colorado River by boat from Green River, Wyoming to Callville,

Nevada (now under Lake Mead). In 1871-72, Powell returned to lead a second expedition

through the Grand Canyon. This second

expedition produced the first accurate maps of the area and over 100

photographs that enthralled the American population.

Legacy of the Pathfinders

The Spanish spent almost 300

years looking for gold and establishing missions in Arizona, followed by three

decades of Anglo-American mountain men trapping Arizona’s rivers in the fur

trade. Neither group was concerned with

establishing transportation routes across the future state. That changed with the War with Mexico in

1846, when the U.S. wanted to support California from the East, and after the

war, when the California Gold Rush, the hunger for trade, and the desire for

transcontinental railroads - all generated a need for reliable, efficient

pathways that crossed Arizona between the East and the Pacific Coast.

Two major paths developed in

Arizona - one in southern Arizona and the other in northern Arizona. From these core routes, an extensive network

of stagecoach, railroad, and eventually automobile routes would develop.

Southern Arizona. The western part of the historic Gila

Trail, from Yuma to Tucson, first used by Juan Bautista de Anza in 1775, became

the western part of Arizona’s southern overland route. Beginning in 1849, thousands of gold seekers

used the route, linked with Philip St. George Cooke’s Wagon Road or Lawrence

Pike Graham’s route in eastern Arizona.

The path surveyed in eastern Arizona by John G. Parke in 1855, eventually

became the eastern variant of choice for the southern overland route.

The San Antonio to Texas Mail

Line used this general route for stagecoaches in 1857, followed by the

Butterfield Overland Mail Line - from Missouri, via El Paso, Tucson, and Los

Angeles, to San Francisco - that operated stagecoaches over the same

cross-Arizona route from 1858-1861.

The Southern Pacific Railroad

finished laying tracks on the same line across Arizona in 1880, and in 1881,

linked up with the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad in New Mexico to

complete Arizona’s first transcontinental railroad.

Finally in the 1960s and 1970s,

the current Interstate Highway System (Interstate 8 from Yuma to Casa Grande,

and Interstate 10 from Casa Grande to the New Mexico border east of Wilcox, was

built on the same basic southern overland route.

Northern Arizona. Arizona’s northern overland route

developed from the explorations of Lorenzo Sitgreaves in 1851, the surveys of

Amiel W. Whipple in 1854, and the completion of Edward F. Beale’s Wagon Road in

1860.

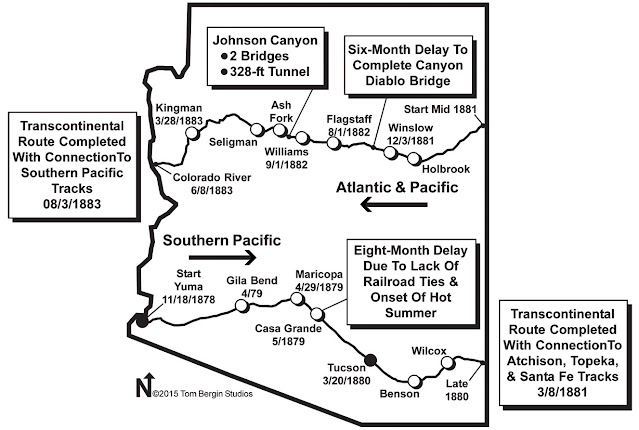

In 1883, the Atlantic &

Pacific Railroad completed Arizona’s second transcontinental railroad,

basically along Whipple’s surveyed path.

There were never any direct

stagecoach routes across northern Arizona, but in 1926-1938, the historic Route

66 automobile road was built between Chicago and Los Angeles, passing though

Arizona in the same corridor as the transcontinental railroad.

And finally, as part of the

current U.S. Interstate Highway System, Interstate 40 was completed across

northern Arizona in 1984, generally replacing Route 66.

Arizona's two transcontinental railroads opened up the territory for development.

Arizona’s Development. The two transcontinental railroads

immediately contributed to Arizona’s development. New towns had been established along the

railroad routes, including Gila Bend, Maricopa, Casa Grande, Benson, and Wilcox

in the south, and Holbrook, Winslow, Flagstaff, Williams, Ash Fork, Seligman,

and Kingman in the north. Settlers were

now able to reach Arizona in large numbers - effectively ending the Arizona

frontier.

Cattle ranching in the south

expanded rapidly. Big money investors

shipped cattle into Arizona from various locations around the country,

particularly from Texas, where cattlemen were looking to escape mandatory

grazing fees on state lands. In the

north, cattlemen began to exploit the lush grasslands of the Little Colorado

River Basin in east-central Arizona.

Mining also increased dramatically

in the south. The railroad brought heavy

equipment that enabled efficient mining development in places like Tombstone

and Bisbee

Over the decades following the

building of the transcontinental railroads, connection railroads were built

between the transcontinental railways, and shorter lines were built to outlying

towns and mines. By 1900, Tucson,

Prescott, Phoenix, Nogales, Globe, Tombstone, and Bisbee were connected by

railroad. This slowly expanding rail

network helped the Arizona Territory to develop along with the railroad.

By the time Arizona became a

state in 1912, the transcontinental railroads had enabled Arizona’s early

critical economic drivers - the “five C’s” of copper, cattle, cotton, citrus,

and climate - to firmly take hold.

Arizona was now exporting copper, cattle, cotton, and citrus, and

importing people attracted by the state’s fabulous climate and natural wonders.

Arizona’s development continued

with the creation of a national highway system, beginning in the 1920s, and the

start of the Interstate Highway System in the 1960s.

Comments

Post a Comment