HISTORY44 - Major Cross-Country Automobile Roads

My previous blog was about the history of Flagstaff, Arizona, a city in northern Arizona that was/is a stop on numerous cross-country transportation routes, including the famous Route 66 and today’s Interstate 40. That sparked a desire to learn more about the history of cross-country automobile roads, the subject of this blog.

After a short introduction, I’ll

talk about the history of the little-known transcontinental Lincoln Highway,

the much more well-known Route 66, and finally, the Interstate Highway System. I’ll begin in 1912, the year America got

serious, about longer distance roads.

My principal sources include “A

Brief History of the Lincoln Highway,” lincolnhighwayassoc.org/history/; “The History

of Route 66,” national66.org/history-of-route-66; The Interstate Highway

System,” history.com/topics/us-states/interstate-highway-system; “The Complex

History of the United States Interstate Highway System,”

interestingengineering.com; “Future Interstate Study,” trb.org/FutureInterstateStudy.aspx;

plus, numerous other online sources.

In

1912, the year the Continental United States was completed with the admission

of Arizona to statehood, railroads dominated long distance and interstate

transportation. Four transcontinental

railroad routes had been built in the 1880s and 1890s. Between then and 1912, a network of

connecting railways had been constructed all over America.

There were almost no good automobile roads in 1912. The

relatively few miles of improved roads were only around towns and cities. A road was “improved” if it was graded; one

was lucky to have gravel or brick.

Asphalt and concrete were yet to come. Most of

the 2½ million miles of roads were just dirt: bumpy and dusty in dry weather,

impassable in wet weather.

A car stuck in the mud near Tama, Iowa in 1919.

Worse yet, the roads didn’t really lead anywhere. They spread out aimlessly from the center of

town. Outside cities and towns, there were almost

no gas stations or even street signs, and rest stops were unheard-of.

To get from one city or town to another, it was much easier

to take the train.

This was about to change. In 1908, Henry Ford had introduced the Model

T, a dependable, affordable car that soon found its way into many American

households. By 1912, there were an increasing number of both automobiles and

drivers - with places to go.

Lincoln Highway

In the early 1900s, before a nationwide network of

numbered highways was adopted by the states, an informal network of privately-funded auto trails existed in

the United States. Marked with colored bands on utility

poles, the trails were intended to help travelers in the early days of

the automobile.

Another assist to

drivers in the early 1900s were roadmaps.

The first truly useful motorist guidebook emerged in

1901, with maps covering Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Washington, and

Baltimore. These first roadmaps didn’t

contain every road. Instead, there was a

list of instructions guiding drivers from one place to another using mileage

between towns, mileage between each instruction, and local landmarks. It might say at mile 58.5, “left-hand turn

just before railroad,” or “turn right away from poles.” The book included stops where drivers could

find gasoline, lubricants, or repair shops, or a place to charge their electric

vehicles. (See my March 27, 2021 blog,

“The Promise of Electric Vehicles.”) The

guide’s popularity increased significantly in 1906, when AAA became its

official sponsor, and expanded to 10 volumes covering most of the country the

following year.

But the guide had its

competitors. In 1904, mapmaker Rand

McNally printed its first automobile road map of New York City and

vicinity. Three years later, the company

undertook publication of the Photo-Auto Guides from Gardner Chapin. The guide combined maps and photos with

arrows to indicate turns. In 1915, cartographer George Coupland Thomas

developed a unique page-by-page grid system of mapping that eliminated the need

for a folding map. McNally loved it. By 1924, Rand McNally’s Auto Chum appears,

the first edition of what becomes Rand McNally Road Atlas.

The Vision. In 1912, Carl Fisher, an

early automobile enthusiast who had been a racer, the manufacturer of

Prest-O-Lite compressed carbide-gas headlights used on most early motorcars,

and the builder of the Indianapolis Speedway, proposed a graveled highway

spanning the continent from coast to coast.

Carl Fisher, builder of the Indianapolis Speedway, conceived and helped develop the Lincoln Highway.

Communities

along the route would provide the road building equipment and in return would

receive free materials and recognition as a place along America’s first

transcontinental highway.

To fund

this scheme, Fisher received cash donations from auto manufacturers and

accessory companies. The public could become members of the highway

organization for $5 (about $28 dollars today).

Henry Joy, president of the Packard Motor Car Company, wholeheartedly supported the project and became the primary

spokesman for the highway. He came up

with the idea of naming the highway after Abraham Lincoln.

Implementation. On July 1, 1913, a group

of automobile enthusiasts and industry officials established the Lincoln

Highway Association (LHA) "to procure the establishment of a continuous

improved highway from the Atlantic to the Pacific, open to lawful traffic of

all description without toll charges."

Henry Joy was elected as

president. Carl Fisher, was elected vice-president.

The LHA had two

goals. One goal was to build a

"Coast-to-Coast Rock Highway" from Times Square in New York City to

Lincoln Park in San Francisco. The second goal was to make the Lincoln Highway

an object lesson that would, in the words of its creator, Carl G. Fisher,

"stimulate as nothing else could the building of enduring highways

everywhere that will not only be a credit to the American people but that will

also mean much to American agriculture and American commerce." The LHA's founders wanted the shortest, most

direct route possible between the two points.

The route did not deviate

from a straight path in order to go through larger cities or national

parks. That initial road was

3,389 miles long. Less than half of it,

1,598 miles, was improved. (Eventually, as segments of the route were improved,

the length shrunk to about 3,140 miles.)

The route of the Lincoln Highway, including a northern and southern route option in California around the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

The LHA dedicated the

route of the Lincoln Highway on October 31, 1913.

At a time when a

service infrastructure to support the automobile did not exist, motorists were

urged to buy gasoline at every opportunity, no matter how little had been used

since the last purchase.

For the most part,

the LHA used contributions for publicity and promotion to encourage travel over

the Lincoln Highway, as well as to encourage state, county, and municipal

officials to improve the road. The LHA did, however, help finance construction

of short sections of the route.

One of the Lincoln

Highway's greatest contributions to future highway development occurred in

1919, when the U.S. Army undertook its first transcontinental motor convoy,

taking 62 days on the road from Washington D.C. to Oakland, California. The

convoy suffered many setbacks and problems on the route, such as poor-quality

bridges, broken crankshafts, and engines clogged with desert sand. One participant in

the convoy was young Army officer, Lt. Colonel Dwight David Eisenhower. That difficult experience, plus his

observations of the efficient German Autobahn network during World War II,

convinced him to support construction of the Interstate Highway System when he

became President.

By the mid-1920s, the

Nation was crisscrossed by a network of approximately 250 mostly unimproved named

trails. Some were major intercontinental routes, such as the Lincoln Highway; the

National Old Trails Road, between Baltimore, Maryland and Los Angeles,

California; the Old Spanish Trail, between St. Augustine, Florida and San

Diego, California; and the Jefferson Highway, between Winnipeg, Manitoba and

New Orleans, Louisiana. But most named

trails were shorter. They had become a confusing tangle, often on routes

selected more because of the willingness of local groups to pay

"dues" to a trail association than because of transportation value.

Some of the trail organizations were fly-by-night groups that were more

interested in "dues" than road.

Sometimes, where several

named highways shared a route, almost an entire pole would be striped in

various colors.

Also, by the mid-1920s, the Ford

company had sold nearly 15 million cars. Ford’s competitors had followed its lead and

begun building cars for everyday people. “Automobiling” was no longer an

adventure or a luxury: It was a necessity.

A nation of drivers needed good roads, but

building good roads was expensive. Who would pay the bill? Automobile interests - such as car companies,

tire manufacturers, gas station owners, and suburban developers - needed to convince

national, state and local governments that roads were a public concern. That way, they could get the infrastructure

they needed without spending any of their own money.

National Highway

System.

In 1925, federal and state officials established the Joint Board on

Interstate Highways to plan for interstate highway construction. The plan also created

the U.S. Numbered Highway System to replace the old trail designations. All named

roads were ignored in their planning. The

Secretary of Agriculture approved the plan, which set up the now-familiar U.S.

highway system. The Federal Government

was the coordinating agency, with most of the funding for highway construction

provided by state and local governments.

Generally,

east-to-west highways were even-numbered, with the lowest numbers in the north,

and the highest in the south. North-to-south

highways were typically odd-numbered, with the lowest numbers in the east and

the highest in the west. Major east-west

routes usually had numbers ending in "0,” while major north-south routes

generally had numbers ending in "1" or "5.” Three-digit numbered highways were generally

spur routes of parent highways. (These guidelines were not rigidly followed,

and many exceptions exist.)

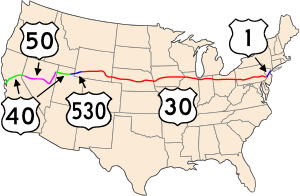

The

Lincoln Highway was broken up into U.S. 1, U.S. 30, U.S. 530, U.S. 40, and U.S.

50. Nearly two-thirds of the Lincoln

Highway’s length was designated as U.S. 30. The Nation also adopted a standard

set of road signs and markers, and to avoid confusion, all markers of all named

roads were taken down.

The Lincoln Highway was broken up into these numbered highways.

The States approved

the U.S. numbering system in November 1926 and began putting up the newly

approved signs.

Legacy. The Lincoln Highway was

the Nation's premier highway, but it never quite measured up to the dreams of

its founders; it was never quite finished.

But its success helped the country achieve the LHA's goal of enduring

highways everywhere.

While the

other named highways were quickly forgotten, the Lincoln Highway was not. A whole generation of Americans, exposed to

the well-organized publicity of the Lincoln Highway Association, kept the

Lincoln Highway alive long after its official significance was gone.

Route 66

The

original inspiration for an improved roadway between Chicago and Los Angeles

came from entrepreneurs Cyrus Avery of Tulsa, Oklahoma, and John

Woodruff of Springfield, Missouri. The pair lobbied the American

Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO) for the creation of a route

following the 1925 plans.

Entrepreneur Cyrus Avery of Tulsa, Oklahoma, lobbied for an improved highway between Chicago and Los Angeles.

Planning. Officially,

the numerical designation 66 was assigned to the Chicago-to-Los Angeles route

in the summer of 1926. With that designation came its acknowledgment as one of

the nation’s principal east-west arteries.

From

the outset, public road planners intended U.S. 66 to connect the main

streets of rural and urban communities along its course for the most practical

of reasons: most small towns had no prior access to a major national

thoroughfare.

Route

66 did not follow a traditionally linear course. Its diagonal course linked hundreds of

predominantly rural communities in Illinois, Missouri, and Kansas to Chicago,

thus enabling farmers to transport grain and produce for redistribution. The

diagonal configuration of Route 66 was particularly significant to the trucking

industry, which by 1930 had come to rival the railroad for preeminence in the

American shipping industry. The route between Chicago and the

Pacific coast traversed essentially flat prairie lands and enjoyed a more

temperate climate than northern highways, which made it especially appealing to

truckers.

The path of Route 66 between Chicago and Los Angeles.

Implementation

and Place in Americana. Cyrus Avery called for the establishment of

the U.S. Highway 66 Association to promote the complete paving of the

highway from end to end, and to promote travel along the highway. In 1927, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the Association

was officially established with John Woodruff elected the first president.

Much

of the early highway, like all the other early highways, was gravel or graded

dirt. During its nearly 60-year existence, U.S. 66

was under constant change. As highway engineering became more sophisticated,

engineers constantly sought more direct routes between cities and towns. Many sections of U.S. 66 underwent major

realignments.

The Dust Bowl

of the 1930s, a period of extreme drought and dust storms in the Plains

states, saw many farming families, mainly from Oklahoma, Arkansas, Kansas,

and Texas, heading west on Route 66 for agricultural jobs in California. In his famous social commentary, The

Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck proclaimed U.S. Highway 66 the “Mother

Road.” Steinbeck’s classic 1939 novel,

combined with the 1940 film recreation of the epic odyssey, served to

immortalize Route 66 in the American consciousness. An estimated 210,000 people migrated to

California to escape the despair of the Dust Bowl. Certainly, in the minds of those who endured

that particularly painful experience, and in the view of generations of

children to whom they recounted their story, Route 66 symbolized the “road to

opportunity.”

During

the Great Depression, Route 66 gave some relief to communities located on the

highway. The route passed through numerous small towns and, with the growing

traffic on the highway, helped create the rise of mom-and-pop businesses,

such as service stations, restaurants, and motor courts, all

readily accessible to passing motorists.

From

1933 to 1938, thousands of unemployed male youths from virtually every state

were put to work as laborers on road gangs to pave the final stretches of the

road. As a result of this monumental

effort, the Chicago-to-Los

Angeles highway was reported as “continuously paved” in 1938, the first U.S.

highway to be completely paved - at a total length of 2,448 miles.

Completion

of this all-weather capability on the eve of World War II was particularly

significant to the Nation’s war effort.

At the outset of American involvement in World War II, the War

Department singled out the West as ideal for military training bases, in part

because of its geographic isolation, and especially because it offered

consistently dry weather for air and field maneuvers.

During World War II, additional migration

westward occurred because of war-related industries in California. U.S. 66, already popular and fully

paved, became one of the main routes, and also served for moving military

equipment.

After World War II, in the 1950s, Route 66

became the main highway for vacationers heading to Los Angeles. The road passed

through the Painted Desert and near the Grand Canyon.

Meteor Crater in Arizona was another popular stop.

Store owners, motel managers, and gas station

attendants recognized early on that even the poorest travelers required food,

automobile maintenance, and adequate lodging. Just as New Deal work relief

programs provided employment with the construction and the maintenance of Route

66, the appearance of countless tourist courts, garages, and diners promised

sustained economic growth after the road’s completion. If military use of the

highway during wartime ensured the early success of roadside businesses, the

demands of the new tourism industry in the postwar decades gave rise to modern

facilities that guaranteed long-term prosperity.

Tourism along Route 66 spawned the building of all sorts of motels, such as this iconic Wigwam Village in Holbrook, Arizona.

One such traveler was Bobby Troup, former pianist

with the Tommy Dorsey band and ex-Marine captain. He penned a lyrical road map of the now

famous cross-country road in which the words, “get your kicks on Route 66”

became a catch phrase for countless motorists who moved back and forth between

Chicago and the Pacific Coast. The popular recording was released in 1946 by

Nat King Cole, one week after Troup’s arrival in Los Angeles.

Route

66 and many points of interest along the way were familiar landmarks by the

time a new generation of postwar motorists hit the road in the 1960s. It was during this period that the television

series, “Route 66,” starring Martin Milner and George Maharis, drove into the

living rooms of America every Friday.

The TV series brought Americans back to the route looking for new

adventure.

Martin Milner and George Maharis starred in the Route 66 television series in 1960-1963.

Excessive

truck use during World War II, and the comeback of the automobile industry

immediately following the war, brought great pressure to bear on America’s

highways. The National Highway System had deteriorated to an appalling

condition. Virtually all roads were functionally obsolete and dangerous because

of narrow pavements and antiquated structural features that reduced carrying

capacity.

The

Interstate Highway System. The beginning of the decline for U.S. 66

came in 1956 with the signing of the Interstate Highway Act by

President Dwight D. Eisenhower. The legislation provided a comprehensive

financial umbrella to underwrite the cost of the National Interstate and Defense

Highway System.

At

the time, the U.S. Numbered Highway System was a dense network of roads

crisscrossing the entire country, and had reached a total length of almost

158,000 miles.

The

outdated, poorly maintained vestiges of U.S. Highway 66 completely succumbed to

the interstate system. By 1970, nearly

all segments of the original Route 66 were bypassed by a modern four-lane

highway. In October 1984, the final section of the

original road was bypassed by Interstate 40 at Williams, Arizona.

With

the decommissioning of U.S. 66, no single interstate route was designated

to replace it, with the route being covered by Interstate 55 from

Chicago to St. Louis, Interstate 44 from St. Louis to Oklahoma City,

Interstate 40 from Oklahoma City to Barstow, Interstate 15 from

Barstow to San Bernardino, and a combination of California State Route

66, Interstate 210, and State Route 2 or Interstate 10, from

San Bernardino across the Los Angeles metropolitan area to Santa Monica.

Legacy. When

the highway was decommissioned, sections of the road were disposed of in

various ways. Within many cities, the

route became a "business loop" for the interstate. Some sections

became state roads, local roads, private drives, or were abandoned

completely. Although it is no longer

possible to drive U.S. 66 uninterrupted all the way from Chicago to Los Angeles,

much of the original route and alternate alignments are still drivable with

careful planning.

Some

states have kept the “66” designation for parts of the highway, albeit as state

roads. In Missouri, Routes 366, 266, and 66 are all

original sections of the highway. State Highway 66 in Oklahoma

remains as the alternate "free" route near its turnpikes. "Historic Route 66" runs for a

significant distance in and near Flagstaff, Arizona. Farther west, a long segment of U.S. 66

in Arizona runs significantly north of Interstate 40, and much of it is

designated as State Route 66.

On

old Route 66 in Winslow, Arizona, there is park named “Standin’ in the Corner

Park,” that commemorates the song, “Take it Easy,” recorded by the Eagles in

1972. The song includes the verse,

“Well, I’m standin’ on a corner in Winslow, Arizona and such a fine sight to

see. It’s a girl, my Lord, in a flatbed

Ford slowin’ down to take a look at me.”

The Park was developed to spark a renaissance of Winslow after

Interstate 40 bypassed the community.

In August 2021, Pat and I visited Standin' on the Corner Park in Winslow, Arizona.

Various

sections of the Route 66 have been placed on the National Register of

Historic Places.

Many

preservation groups have tried to save and even landmark the

old motels and neon signs along the road in some states.

In

1999, President Bill Clinton signed a National Route 66

Preservation Bill that provided for $10 million in matching fund

grants for preserving and restoring the historic features along the route.

In

2008, the World Monuments Fund added U.S. 66 to the World

Monuments Watch as sites along the route such as gas stations, motels,

cafés, trading posts, and drive-in movie theaters are threatened by development

in urban areas and by abandonment and decay in rural areas. The National Park

Service developed a Route 66 Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel

Itinerary describing over one hundred individual historic sites. As the popularity and mythical stature of

U.S. 66 has continued to grow, demands have begun to mount to improve

signage, return U.S. 66 to road atlases, and revive its status as a

continuous routing.

Route

66 symbolized the renewed spirit of optimism that pervaded the country after

economic catastrophe and global war. Often called, “The Main Street of America,”

it linked a remote and under-populated region with two vital 20th

century cities - Chicago and Los Angeles.

Interstate Highway System

After

he became U.S. President in January 1953, Dwight Eisenhower

appointed General Lucius D. Clay to investigate the need for an

interstate highway system. Clay stated that, it was evident we needed better highways for

safety, to accommodate more automobiles, and defense purposes, if that should

ever be necessary. He also noted that

we also needed them for the economy, not just as a public works measure, but

for future growth.

General

Clay came up with a plan to build 40,000 miles of divided

highways that would link all of America's cities having a population

of 50,000 or greater.

Construction. With

the passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, construction got underway of the Dwight

D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, commonly

known as the Interstate Highway System (IHS).

President Dwight Eisenhower signed off on the Interstate Highway System in 1956.

Each

interstate highway was required to be a controlled-access

highway with at least four lanes, and no at-grade (same level)

crossings. Controlled-access highways

would have on- and off-ramps, and were designed for high-speed traffic. While some older freeways were adopted into the system,

most of the routes were completely new construction, greatly expanding the

freeway network in the U.S.

Missouri

was first state off the block, when on August 13, 1956, work began in St.

Charles County on U.S.-40, which is now named I-70. The Interstate Highway System was considered

finished on October 14, 1992 with the completion of I-70 through Glenwood

Canyon in Colorado; it is considered to be an engineering marvel with

a 12-mile span containing 40 bridges and numerous tunnels.

In 1966,

the Interstate Highway System was designated as part of the Pan-American Highway System,

linking Canada, the U.S. and Mexico.

The complete U.S. Interstate Highway System 2018.

Some of these new freeways, especially in densely

populated urban areas, were controversial, as their building necessitated the

destruction of many older, well-established neighborhoods. There were many “freeway revolts” during

the 1960s and 1970s, including in such metropolitan areas as the District of

Columbia, Indianapolis, Baltimore, New York City, San Francisco, and

Boston. Several planned interstates were

abandoned or re-routed to avoid urban cores.

Though much of their construction was funded by the

federal government, interstate highways are owned by the state in which they

were built.

About 70% of the construction and maintenance costs of interstate

highways in the United States have been paid through user fees, primarily

the fuel taxes collected

by the federal, state, and local governments. To a much lesser extent, they

have been paid for by tolls collected on toll highways and bridges.

The rest of the costs of these highways are borne by general fund receipts,

bond issues, designated property taxes, and other taxes.

Toll Roads. Federal legislation initially banned the

collection of tolls, but some of the new interstate routes became toll

roads, either because they were grandfathered into the system, or because

subsequent legislation allowed for tolling of interstates in some cases.

Some large sections of interstate highways that were

planned or constructed before 1956 are still operated as toll roads, for

example the Massachusetts Turnpike (I-90), the New York State

Thruway (I-87 and I-90), and the Kansas Turnpike (I-35, I-335,

I-470, I-70). Others have had their construction

bonds paid off and they have become toll-free, such as the Connecticut

Turnpike (I‑95), the Richmond-Petersburg Turnpike in Virginia

(also I‑95), and the Kentucky Turnpike (I‑65). About 2,900 miles of toll roads are included

in the Interstate Highway System today.

Numbering

System. The Interstate Highway System utilizes a

numbering system whereby primary roads have one- or two-digit numbers, and

shorter routes have three-digit numbers, with the last two digits matching the

parent route. For example, I-787 in Albany, New York is a short spur that

attaches to I-87. Major arteries that span long distances were

assigned numbers that are divisible by five.

East-west highways are even-numbered, while north-south highways are

odd-numbered. Even-numbered routes increase going from south

to north, and odd-numbered routes increase when going from west to east

(opposite of original Numbered Highway System). For example, north-south I-5

runs between Canada and Mexico along the West Coast, while I-95, which spans

between Canada and Miami, Florida, runs along the East Coast. West-east

arteries include I-10, which spans between Santa Monica, California, and

Jacksonville, Florida, and I-90, which runs between Seattle, Washington, and

Boston, Massachusetts. There are no

"I-50" and "I-60" because other U.S. highways currently use

those numbers.

Odd and even IHS numbering system.

The

Interstate Highway System extends to Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico. In Hawaii, the interstates are all located on

the Island of Oahu, and they all

have the prefix "H". For example, there are H-1, H-2, H-3, and H-201.

Interstates

in Alaska and Puerto Rico are numbered sequentially in the order of their

funding, and they have the prefixes "A" and "PR",

respectively.

For

one- or two-digit interstates, mile marker numbering begins at their southern-

or western-most points. If an interstate originates within a state, then mile

marker numbering starts at the southern or western state line.

Exit

numbers of interstates are either sequential, or else distance-based, so that

the exit number is the same as the nearest mile marker. For locations having

multiple exits within the same mile, exit numbers are assigned letter suffixes.

Business

loops or spurs are routes that intersect an interstate and go through a city's

central business district. A city may

have more than one business loop. Business loop signs are green shields which

differ from the regular Interstate Highway System's red and blue shields.

IHS regular and business loop shields.

Currently,

speed limits on interstates are set by the individual states and range from

50-80 mph, depending on whether or not the road is in open country or in a sharp-turn

urban environment.

IHS

Impacts. The Interstate Highway System's impact on the

U.S. has been enormous. It caused a sharp decline in both railway shipping and passenger traffic, while at the same

time, the trucking industry expanded. This caused a drop in the cost of

shipping goods.

The

Interstate Highway System is responsible for the explosive grown of suburbs

during the late 1950s and 1960s. The new roadways linked

suburban homes to jobs located in the cities.

The

IHS also is also responsible for the "road trip,” where entire families

packed into the car and hit the road. This, in turn, led to the creation of

visitor attractions, service stations, motels, and restaurants.

The

Interstate Highway System has been blamed for the decline of cities not on the

highway's grid, and for the decay of urban centers.

As one of the components of the National Highway

System, interstate highways improve the mobility of military troops to and from

airports, seaports, rail terminals, and other military bases.

The IHS has also been used to facilitate evacuations in

the face of hurricanes and other natural disasters. An option for maximizing traffic throughput on

a highway is to reverse the flow of traffic on one side of a divider so that

all lanes become outbound lanes. This procedure, known as contraflow lane

reversal, has been employed several times for hurricane evacuations.

Statistics. In 2020, there were about 290 million cars on

U.S. roads.

About one-quarter of all vehicle miles driven in the

country used the Interstate Highway System.

Today, the IHS is comprised of 48,440 miles of roadway. It was initially estimated to cost $25 billion and take 12 years to complete. It actually ended up costing $114 billion ($530 billion in 2019 dollars) and took 35 years to complete.

Typical interstate highway in open country.

Some

additional statistics: The heaviest

traveled interstate is I-405 in Los Angles California at 374,000 vehicles per

day. The highest elevation interstate is

I-70 in the Eisenhower Tunnel at the Continental Divide in the Colorado Rocky

Mountains. The longest east-west

interstate, at 3,020 miles, is I-90 from Boston, Massachusetts to Seattle,

Washington. The longest north-south

interstate, at 1,908 miles, is I-95 from the Canadian border, near Houlton,

Maine to Miami, Florida. With 26 lanes in certain parts, the Katy Freeway,

or Interstate 10, is the widest highway in the world. It serves more than

219,000 vehicles daily in Houston, Texas.

Future of Interstate Highway System.

The IHS has continued to expand and grow as additional federal funding

has provided for new routes to be added, and the system will grow into the

future.

But, today, the Interstate Highway System is facing a perfect

storm - while it continues to be a vital mobility network for the Nation, it

risks degradation and obsolescence from aging and excessive wear, and difficulty

accommodating new vehicle technologies.

Many Interstate highway segments are more than 50 years old and

subject to much heavier traffic than anticipated. They are operating well

beyond their design life, made worse by lack of major upgrades or

reconstruction. They also are poorly equipped to accommodate even modest

projections of future traffic growth, much less the magnitude of growth

experienced over the past 50 years.

Example of a complex urban intersection of interstate highways today.

Not only did the U.S. fail to invest appropriately in the past,

funding for the next 20 years is facing a fast-closing window. This 20-year

period coincides with the entire system reaching the end of its design life. At

the same time, it overlaps with the onset of automated, electric, and connected

(to the internet) vehicles.

Congress directed the Transportation Research Board (TRB), a

program unit of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine,

to form a special committee to conduct a study to inform pending and future

federal investment and policy decisions concerning the Interstate Highway

System.

The Board’s recommendations include creating a federal program

dedicated to renew and modernize interstate highways over the next 20 years;

raising additional funds by increasing the federal fuels tax, allowing states

and metro areas to toll more interstates, and possibly adopting mileage-based

use fees; and planning for the transition to electric, automated, and connected

vehicles.

Comments

Post a Comment