HISTORY43 - Flagstaff, Arizona - The City of Seven Wonders

Pat and I have been vacationing in Flagstaff for years. We even have a timeshare there. I figured it was about time to research and document the history of the area.

After a short introduction to

Flagstaff, I cover the early Inhabitants, the founding of Flagstaff, the city’s

development, Route 66 and growth, decline and resurgence, and Flagstaff

today. Principle sources include the

Museum on Northern Arizona; the Flagstaff Visitors Center; “Flagstaff History”

and “Historic Downtown Walking Guide,” flagstaffarizona.org; “Flagstaff,

Arizona - City of Seven Wonders,” legendsofamerica.com; “History of Flagstaff,

Arizona,” “Flagstaff, Arizona,” and “Yavapai,” from Wikipedia; plus numerous

other online sources.

Flagstaff is a city in northern

Arizona, located near the southwestern edge of the Colorado Plateau, alongside

the largest contiguous ponderosa pine forest in the continental United

States. The city sits at 6,910 feet

altitude, next to 9,301-foot Mount Elden, about 10 miles south of Humphrey’s

Peak, the highest point in Arizona at 12,633 feet. Flagstaff is about 80 miles south of the

south rim of the Grand Canyon, and

lies along the Rio de Flag watercourse, about 130 miles north of the State

capital, Phoenix.

Flagstaff

is often called the “The City of Seven Wonders” because it sits in the

midst of the Coconino National Forest and is surrounded by the Grand Canyon, Oak Creek Canyon, Walnut Canyon, Wupatki

National Monument, Sunset Crater National Monument, and the San Francisco

Peaks.

Flagstaff offers a

beautifully mixed landscape of forests, high deserts, lakes, and volcanic

craters. Some

of the open forest space contains bunchgrass, and local animal species

that roam on this include elk, mule deer, Merriam's Turkey,

and Abert's squirrel. Birds that

live around or visit Flagstaff include the thick-billed kingbird, only

documented in the area since 2016, the red-faced warbler,

a Madrean species, and waterfowl including the Eurasian and

American wigeon (shallow water ducks).

Flagstaff

is one of the United States' sunniest and snowiest cities, with a variable

"semi-arid" climate and a monsoon season in summer.

|

| Map of Flagstaff area. |

Early Inhabitants

The first people who inhabited

the Flagstaff region were probably descendants of people who followed herds of

large animals from Siberia across a land bridge in the Bering Strait into

Alaska between about 45,000 BC and 12,000 BC.

Subsequent generations of these Paleo-Indians (ancient ones) gradually

spread southward to populate North America, reaching Arizona in about 9,500

BC. The Paleo-Indian tradition was

followed by the Archaic Period which lasted in Arizona from about 6,000 BC to AD

200. Two Archaic cultures had influence

in the Flagstaff area: the Cochise

culture, that dominated Arizona, and the Basket Maker culture, occupying the

Colorado Plateau in the four-corners region. This was a time of transitions, after the big

game (mammoths, bison, sloths) died off, to hunting smaller game and gathering

a variety of edible wild plants, and most importantly, learning to farm,

leading to permanent small settlements.

Sinagua. The prehistoric Sinagua (Spanish

for “without water”) people occupied a large area in northcentral

Arizona between approximately AD 500 and AD 1425. Sinagua land extended from

the Little Colorado River, northeast of Flagstaff; south to the Verde River near Sedona, including the Verde Valley; the area around

the San Francisco Peaks; and significant portions of the Mogollon

Rim country. The Northern Sinagua

began living in the pine forests of northern Arizona in the 5th

century, before moving into the area that is now Flagstaff in about AD 700.

The Sinagua culture was a combination of hunter-gatherer foraging

and subsistence agriculture. They

hunted a variety of game from antelope, bear, and rabbit, to turtles and ducks.

They used amaranth, ricegrass, cactus fruit, beeweed flowers, and cattails for flour.

Sunflowers, hackberry fruit, yucca, wild grapes, walnuts, pine

nuts, and acorns were also important sources of

food. Sinagua farmers

cultivated maize beginning in the 8th century. They

learned irrigation techniques from their southern Hohokam neighbors and

added beans and squash to their crops.

Eruptions of Sunset Crater between AD 1064-1067 covered

800 square miles of the surrounding land in cinder and ash, which greatly

enriched the soil for farming. Following

this initial period of eruptions, there were intermittent lava flows and

ejections of cinders for the next 200 years.

Early Sinagua sites consist mostly of pit houses, lined

with brush, poles, timbers, or stones. Later structures were masonry pueblos, like

other contemporaneous cultural groups occupying the southwestern United States.

Besides ceremonial kivas, Sinagua pueblos had large "community rooms"

and some featured ballcourts and walled courtyards, similar to those of

the Hohokam culture.

The Sinagua were active in the region's long-distance trade

which reached the West Coast, Gulf

of California, and Mesoamerica. They traded their

baskets and woven cotton cloth for copper, macaws, marine shells, salt, and rare pigments.

There are several archaeological ruins of former Sinagua

settlements to the northeast and east of Flagstaff, each within about 15 miles

of Sunset Crater - all probably finding agricultural benefit from the fertile

ash from the volcano’s eruptions. The most

well-known of these settlements are Wupatki and Walnut Canyon. Other significant Sinagua settlement sites

include Elden Pueblo (in eastern Flagstaff), and a little further east, Rio de

Flag (in today’s Picture Canyon), Winona Village, and Turkey Hill Pueblo.

|

| Wupatki, occupied from AD 500-1225, had over 100 rooms, a community room, a ballcourt, and two kiva-like structures. |

|

| The Sinagua occupied over 80 Walnut Canyon cliff dwellings like this one from AD 1100-1250. |

The Northern Sinagua culture started to decline in the

early 13th century and by the mid-14th century had

disappeared. The Southern Sinagua hung around a little longer, abandoning their

Verde Valley sites by the early 15th century. Like other pre-Columbian cultures in the

southwest, the precise reasons for such a large-scale abandonment are not yet

known; resource depletion, drought, and clashes with the newly

arrived Yavapai people have been suggested. Some of the Sinagua likely moved northeast,

becoming the Hopi. The San

Francisco Peaks (which mark the city of Flagstaff's northern border) are a

sacred site in Hopi culture.

Yavapai. Most archeologists agree that the Yavapai

Native Americans in Arizona originated from Patayan groups who

migrated east from the Colorado River region. Archeological and linguistic evidence suggests

that the Yavapai people began developing independently from

the Patayan at around AD 1300. Until American western expansion, the

Yavapai, specifically the Northeastern Yavapai, occupied the land around

Flagstaff up to the San Francisco Peaks.

The

Yavapai were mainly hunter-gatherers, following an annual path, migrating

to different areas to follow the ripening of different edible plants and

movement of game. Some tribes

supplemented this diet with small-scale cultivation of corn, squash,

and beans - in fertile streambeds.

The

main plant foods gathered were walnuts, saguaro fruits, juniper

berries, acorns, sunflower seeds, manzanita berries and

apples, hackberries, the bulbs of the Quamash, and plant greens.

Agave was the most crucial harvest, as it was the only plant food available

from late fall through early spring. The

hearts of the plant were roasted in stone-lined pits, and could be stored for

later use. Primary animals hunted

were deer, rabbit, jackrabbit, quail, and woodrat. Fish and

water-borne birds were eschewed by

most Yavapai groups.

The

Yavapai built brush shelter dwellings. In summer, they built simple lean-tos

without walls. During winter months, closed huts would be built

of ocotillo branches or other wood, and covered with animal skins,

grasses, bark, and/or dirt. They also sought shelter in caves or

abandoned pueblos to escape the cold.

The

Yavapai lived in local groups of extended families, that would form bands in

times of war, raiding, or defense. Most

food-providing sites were not large enough to support larger populations.

Government

among the Yavapai tended to be informal. There were no tribal chiefs. Certain men became recognized leaders based

on others choosing to follow them, heed their advice, and support their

decisions.

After about the mid-18th century, Yavapai groups had

tumultuous relations with the nearby Havasupai and Hualapai people. Though the Pai peoples all spoke the same dialects

and had a common cultural history, each peoples had tales of a dispute that

separated them from each other.

Tonto Apache. The Yavapai land in the Flagstaff area saw

overlap with Northern Tonto Apache land that stretched across the San

Francisco Peaks to the Little Colorado River.

Two Northern Tonto Apache tribes lived within the area of present-day

Flagstaff: the Oak Creek band

and the Mormon Lake band. The

Oak Creek band mixed with the Yavapai and was largely centered near Sedona, but

lived as far north as Flagstaff. The Mormon Lake band consisted entirely of

Apache and were centered around Flagstaff. The Mormon Lake band also faced off

against the Navajo to the north and east. They were exclusively hunter-gatherers, and

traveled around places like the foot of the San Francisco Peaks, at Mount

Elden, Lake Mary, Stoneman Lake, and Padre Canyon.

Note: From here on in this paper, I’m dropping the

anno Domini (AD) notation for dates.

Spanish. Flagstaff did not have a colonial Spanish

presence. Spanish explorers and

missionaries got close, but never reached Flagstaff. In 1540, García López

de Cárdenas, on a side trip from Hernando Coronado’s expedition seeking the Seven

Cities of Gold, discovered the Grand Canyon, but no Spanish returned. In

1604-1605, Juan de Oñate made an extensive exploration of today’s Arizona,

marching west from New Mexico, past the Zuni and Hopi villages in Arizona,

reaching the Verde Valley and the Prescott area, finally arriving at the

Colorado River, and then heading south to the Gulf of California, but missed

the Flagstaff area. Later in the 17th century,

Spanish missionaries, about 65 miles away in the Hopi village of Oraibi, gave the

San Francisco Peaks their name.

Founding of Flagstaff

Soon after Arizona became American territory, following the War

with Mexico in 1848, the U.S. Congress acted to explore the Nation’s new lands,

sending out various parties to find resources, make maps, and locate routes

from the East across the new lands to California, where a gold rush was

happening. In 1851, Captain Lorenzo

Sitgreaves led an Army expedition to explore northern New Mexico and northern

Arizona to the Colorado River, and then south to Yuma. In northern Arizona, the expedition found a

spring and named it after Sitgreaves guide, Antoine Leroux. Leroux Springs was about seven miles

northwest of today’s Flagstaff. A

supplies station was established there in 1856.

Sitgreaves National Forest, along the Mogollon Rim and the White

Mountains in east-central Arizona, was named after Lorenzo Sitgreaves.

In 1853, Army Lt. Amiel Weeks Whipple led an expedition to survey

a possible transcontinental railroad route along the 35th

parallel. By Christmas 1853, the

expedition reached the San Francisco Peaks near present-day Flagstaff, then

continued west, reaching Los Angeles in 1854.

Although Whipple encountered no major obstacles, the 35th

parallel was not chosen for the first transcontinental railroad route due to a

calculation error which added $75 million to his estimate to build a railroad

along the route.

Between 1857 and 1860, Army Lt. Edward Beale was sent to build a

wagon road across northern Arizona.

Beale made sure to stop at Leroux Springs. He sent glowing reports to Congress, telling

them how the Flagstaff area was rich in grasslands, water, and timber. Once the Beale Road was established, it

became well-traveled by emigrants going to California. The travelers noted Flagstaff’s resources as

a treasure chest, but its isolation meant no nearby markets for farm products,

meat, or lumber, and no way to ship goods to distant markets.

|

| Beale's Wagon Road brought Flagstaff to the attention of the nation. |

Meanwhile, Arizona was attracting an increasing number of miners

and settlers from the East. Arizona

Native Americans fought hard to resist encroachment on their tribal lands and

practices. Between 1851 and 1886, there

were a series of “Indian Wars” across Arizona.

In the end, superior American military resources won the war of

attrition. In northern and central

Arizona, the Navajo, the Hualapai, the Yavapai, and the Apache were decimated,

and the survivors placed on reservations.

After short, brutal wars with the Army, a Military Reserve of 900

square miles was established in 1871 for the Yavapai and Tonto Apache in the

Upper Verde Valley. However, this

Reserve was rescinded by President U.S. Grant in 1875 and the Native Americans,

numbering around 1,700 were forcibly marched to the San Carlos Apache

Reservation east of Phoenix.

The first permanent settlement in the Flagstaff area came in 1876

when Thomas F. McMillan built a cabin just north of present-day Flagstaff and

started a successful sheep ranch where he found grass and water. The isolation of the area was not a problem

to him because wool did not spoil, and could withstand the long, rough journey

to market in Boston.

Another party of emigrants came from Boston in 1876. Originally planning to settle in the Little

Colorado River area near Winslow, they found the area already settled and

decided to move on to California. On

July 4, 1876, the group camped in the Flagstaff area. Supposedly, in honor of the nation’s

centennial, they stripped a pine tree of its branches and bark and raised an

American flag. When they moved on, their

“flag staff” became a landmark for those who followed. So, Flagstaff was founded with a flag raising

ceremony.

The days of isolation ended for the Flagstaff area in 1880, when the

Atlantic and Pacific Railroad began to lay track westward from Albuquerque on

its way to California to complete the country’s third transcontinental railroad. Entrepreneurs quickly found they could

capitalize on the railroad’s construction crews by selling food, supplies, and

entertainment from the supply camps they set up along the line. As the rails neared the San Francisco Peaks,

a small settlement began to take shape by a small spring on the slope of what

is now called Observatory Mesa (or Mars Hill), just west of today’s downtown

Flagstaff. In early 1881, merchants and saloonkeepers set up shop for the

advance parties of workers who were coming to grade and cut ties in the

abundant ponderosa forest. The citizens of the little camp called their new

town Flagstaff, in honor of the landmark. By the fall of that year, Flagstaff

boasted a population of 200 and swiftly became a wild railroad town filled with

saloons, dance halls, and gambling houses.

On August 1, 1882, the railroad finally reached Flagstaff.

As the construction crews moved westward to California, some of

Flagstaff’s citizens followed after them, but others stayed, hoping that the

camp could continue to thrive.

Fortunately for those who stayed, Flagstaff became an established stop

for water servicing the railroad and its passengers. Sheep ranchers began to use the railroad to

transport wool, and cattle ranchers, drawn by the prospect of free or

inexpensive land, realized that they could now affordably ship their beef to

the eastern market. Businessman E. E. Ayers set up a lumber mill before the

railroad got to town, and began shipping lumber within days after the rails

arrived. By winter 1882, Flagstaff was a

firmly established town with a railroad, livestock, and lumber industries and a

service industry of merchants, cafes, hotels, and saloons to serve the

sheepherders, cowboys, lumberjacks, and train travelers.

In 1883, the railroad decided to move their depot about a half

mile east of the Flagstaff settlement so their trains didn’t have to start up

on the steep hillside. One of the local

merchants, P.J. Brannen, saw this as an opportunity and decided to move his

mercantile across from the new depot.

Others followed, building a strip of shops, saloons, and hotels along

what became known as Front Street. As a result, Flagstaff became two

settlements: the original site called

Old Town, and the site near the depot named New Town. Old Town had water, but New Town had commerce

and soon outgrew the older settlement.

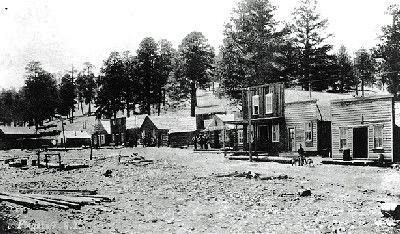

|

| The original Flagstaff, called Old Town, 1882. |

In 1884, a devastating fire burned down many of Old Town’s

buildings, and New Town became the one and only Flagstaff. Its center was the intersection of today’s

Santa Fe Avenue (aka historic U.S Route 66) and San Francisco Street.

The name Flagstaff was reinstated in 1884 when a post office was introduced

alongside the railroad depot.

Development

During the 1880s, Flagstaff began to grow, with the early

economy based on timber, sheep, and cattle. By 1886, Flagstaff was the largest city on the

railroad line between Albuquerque and the West Coast of the United

States. The city had a population of 600

and "more saloons than all other businesses combined.”

In 1886, the (several) Babbitt brothers started and began

to work the CO Bar Cattle Ranch on lands between Flagstaff and the Grand

Canyon. (The Babbitts saw the height of

their "cattle empire" between 1907 and 1919, with around 100 ranches

between Kansas and California funded by the brothers in the 40 years after

their arrival in Flagstaff. The historic CO Bar is one of the largest

ranches in the Southwest and continues in operation today.)

The ambitious Babbitt brothers soon expanded their

business interests, opening all kinds of stores, theaters, and even a mortuary

in 1892, investing their money across northern Arizona. In 1888, they established the Babbitt

Brothers general mercantile store in Flagstaff.

The Babbitt family would be very influential in northern Arizona for

decades (One descendant, Bruce Babbitt was Governor of Arizona and President

Bill Clinton's Secretary of the Interior.)

|

| Babbitt Brothers general merchandise store in Flagstaff, 1888. |

In 1888, sheep rancher Thomas McMillan purchased an

unfinished building at the present-day intersection of Leroux Street

and Route 66/Santa Fe Avenue, turning it into a bank and hotel known as

the Bank Hotel. The next year,

stagecoach tours to the Grand Canyon began running from the Bank

Hotel, which also housed an opera house that doubled as an events hall for

entertainment.

|

| Thomas McMillan's Bank Hotel, 1888. |

The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway completed the

track from Williams to the Grand Canyon in 1901. The company could make a

return on its investment through tourism. The $3.95 train ride replaced the

$15.00 eight-hour stagecoach ride from Flagstaff.

By 1890, the young town of Flagstaff

had reached a population of almost 1,000 and had become one of the largest

towns in the territory. It had a

well-developed business district, and homes were being built throughout the

area. But the inhabitants realized that

the town would soon be too big to continue without some kind of formal

organization.

In 1891, with newfound status, and at

the urging of prominent local citizens, Coconino County was split off from

Yavapai County. Flagstaff became the new

county seat, with Thomas McMillan as Chairman of the Board of Supervisors for

the new county. Unfortunately, concerns

such as the regulation of drinking and gambling and most importantly - the need

for water - were not being addressed. In

Flagstaff’s early days, water was provided from Old Town spring and other small

area springs, but with no water close to Flagstaff, several large fires, like

the 1884 fire that burned Old Town, took a hefty toll. A logical solution was to tap the springs in

the San Francisco Peaks, but the cost and logistics were not feasible. Town leaders talked about the need to

incorporate Flagstaff, not only to gain the status it needed to have an

effective local government, but also to allow for the sale of municipal bonds

to pay for the water project. On May 26,

1894, by action of the Coconino County Board of Supervisors, Flagstaff became

an incorporated town.

The city grew rapidly, primarily due to its location

along the east-west transcontinental railroad line. By the mid-1890s, Flagstaff found itself along

one of the busiest railroad corridors in the U.S., with about 80 to 100 trains

traveling through the city every day, destined for Chicago, Los

Angeles, and elsewhere.

In the 1890s, Anglo settler John

Elden established a homestead on lower slopes of the mountain just northeast of

Flagstaff and grazed sheep on the open grasslands below. The mountain became known as Mount Elden.

In 1894, the Lowell Observatory was constructed

on Mars Hill, overlooking the town from the west. Two years later, the specially-designed

24-inch Clark Telescope was installed. (In 1930, the Clark Telescope was used to

discover Pluto.)

|

| Percival Lowell observing Venus from the Lowell Observatory, 1914. |

In 1899, the Northern Arizona Normal School was established,

renamed Northern Arizona University in 1966.

On January 1, 1900, John Weatherford opened

the Weatherford Hotel in Flagstaff.

Weatherford also opened the town's first movie theater in 1911; it

collapsed under heavy snowfall in 1915, but in 1917, Weatherford replaced it

with the Orpheum Theater. The Weatherford Hotel and Orpheum Theater are

still in use today.

|

| John Weatherford's Hotel, 1900. |

|

| Flagstaff's Orpheum Theater, 1917. |

Flagstaff saw its first tourism boom in the early 1900s,

becoming known as the “City of Seven Wonders” - Coconino National Forest, Grand Canyon, Oak

Creek Canyon, San Francisco Peaks, Sunset Crater, Walnut Canyon, and Wupatki.

By the late 1890s, the reservation system was breaking

down and beginning in 1900, the Yavapai and Tonto Apache survivors of the

removal began drifting back to their home country in small family groups. In 1903, a small reservation was established

in Camp Verde, followed by additional small parcels in Middle Verde, Clarkdale,

and Rimrock.

In the

1910 U.S. Census, Flagstaff had a population of about 3,200 people.

The

state of Arizona was admitted to the Union on February 14, 1912.

Route 66 and Growth

The railroad largely controlled Flagstaff - being its

main source of industry and transport - until Route 66 was started

for automobiles in 1926, passing through Flagstaff. Route 66 had been supported by the

businessmen of Flagstaff as early as 1912, knowing that the town was close to

natural wonders that would make it a commercial opportunity.

Flagstaff prospered and grew steadily with the completion of Route 66.

Flagstaff worked hard to be ready for Route 66. Forecasting a rise in tourism, the townspeople

collectively funded the Hotel Monte Vista, which opened on January 1, 1927.

Flagstaff was then

incorporated as a city in 1928 (having the required population of over 3,000

residents), and in 1929, the city's first motel, the Motel Du Beau, was built

at the intersection of Beaver Street and Phoenix Avenue. The local

newspaper described the motel as "a hotel with garages for the better

class of motorists." A number of motor courts, auto services, and

diners sprouted up along Flagstaff’s new highway. (Today, the city still sports

a number of vintage cafes and motor courts along its historic downtown

district.)

Flagstaff's Hotel Monte Vista, 1927.

Flagstaff became a popular tourist stop along Route 66,

particularly due to its proximity to the Grand Canyon, Painted Desert, and the

Petrified Forest National Park. To

combat Route 66, the Santa Fe Railroad (succeed the Atlantic and Pacific

Railroad) opened a new depot in Flagstaff in 1926. As part of the celebrations, Front Street was

renamed Santa Fe Avenue.

The Santa Fe Railroad built this train depot in Flagstaff in 1926. Photo from the 1940s.

In 1927, Flagstaff's primary industry was still timber,

though farming persisted into the 1920s. The city produced the majority of

Arizona's timber supply that year, and was economically powered by the

competing Arizona Lumber and Timber and Flagstaff Lumber companies. In the last years of the decade, tourism took

over, and the face of the main commercial district changed to diners and motels

in place of saloons.

In 1928, the Museum of Northern Arizona, one of the best archeological

museums on the Prehistoric Southwest in the world, opened

just northwest of the city. (Today the

Museum features displays of the biology,

archeology, photography, anthropology, and native art of the Colorado Plateau.)

Starting in 1929, Flagstaff weathered the Depression, and

by the end, was prospering. The

importance of Route 66 to cross-country travel, and thus to Arizona's interests

on a national level, meant that it received a large share of state funding

through the Depression. Flagstaff's unemployed soon became highway construction

workers, and by the end of 1934, Flagstaff had financially recovered to

pre-Depression levels, aided by tax cuts and continued tourism. In 1935, many residents had enough disposable

income to remodel their homes or build new ones. In 1936, based on the city's

continued economic upswing, General Petroleum announced it was

building a new refinery just outside of town. The first hospital in the city was also opened

in 1936.

Route 66 was entirely paved by 1938. Also in 1938, the northern section of State Route

89A, from Sedona to Flagstaff, through Oak Creek Canyon, was paved, providing

easy access from Flagstaff to Sedona, Clarkdale, Jerome, and Prescott.

In 1938, the Snowbowl opened for skiers on the San

Francisco Peaks.

With America’s entry into World War II in 1941, Route 66 was

used to transport military outfits, bringing more prosperity to Flagstaff and doubling its

population. Flagstaff hosted a huge

ammunition dump then, which brought increased business to the surrounding area

and heavy traffic to and from the facility.

Tourism boomed at war’s end, and Arizona’s National Parks, mountains,

and tribal lands drew travelers to the area.

In the 1950s, Route 180 was paved north of the

city to provide better access for Grand Canyon tourists and skiers on the

mountains north of town. Flagstaff

became a seasonal ski resort.

In 1955, the U.S. Naval Observatory joined Flagstaff’s

growing astronomical presence, and established the United States Naval

Observatory Flagstaff Station five miles west of Flagstaff. Pluto's satellite

Charon was discovered there in 1978.

Through the 1950s, the city conducted the Urban Renewal

Project, improving housing quality in the Southside neighborhood that was

largely populated by people of Spanish, Basque,

and Mexican heritage.

At the end of the 1950s, the Glen Canyon Dam was

built north of the city, with the construction efforts requiring a road to

bring in equipment and resources from Phoenix.

That road became Interstate 17 (from Phoenix to Flagstaff) and U.S.

89 (from Flagstaff to Glen Canyon).

Interstate 17 was finally completed in 1978, greatly facilitating

north-south travel, and directly connecting Flagstaff to Phoenix. Until 1962, scientists spent time in

Flagstaff, documenting the archeological history of Glenn Canyon as it was

flooded, making Lake Powell.

Flagstaff grew and prospered through the 1960s, with a

train running through the city on average every eighteen minutes through the

decade. In 1964, the Lowell Observatory was designated as a National

Historic Landmark. Buffalo Park, a large

open park with free-roaming wildlife within the city, was opened in 1966. During the Apollo program in the

1960s, Lowell Observatory’s Clark Telescope was used by the United States

Geological Survey to map the Moon for the lunar expeditions,

enabling the mission planners to choose a safe landing site for the lunar

modules. Astronauts also trained in the cinder cones around

Flagstaff.

By 1970, Flagstaff’s population had grown to over 26,000

people.

Decline and Resurgence

As the baby

boomer generation began to start their own families in the 1970s and

1980s, many moved to Flagstaff, based on its small-town feel, and the

population began to grow again. But

there were not enough jobs to support the many educated individuals moving to

the city

Downtown Flagstaff suffered

a decline in the 1970s and 1980s. Several

historic buildings from the 19th century were destroyed for

construction of new ones, or leveled completely. Downtown became an uninviting place, and many businesses started to

move out of the area, causing an economic and social decline. Sears and J.C.

Penney left the downtown area in 1979 to open up as anchor stores in the

new Flagstaff Mall, joined in 1986 by Dillard's. In 1987, the Babbitt Brothers Trading Company,

a retail fixture in Flagstaff since 1888, closed its doors.

Another factor in

Flagstaff’s decline was the completion of Interstate 40 across northern Arizona

1984. Business was siphoned away from

Route 66 and downtown Flagstaff.

To protect historic

buildings in downtown, the Railroad Addition Historic District was formed

and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1983. That action preserved many important

historical buildings, including the McMillan Building (1886), the Babbitt

Brothers Building (1888), the Waterford Building (1898), the Orpheum Theater

(1917), the Santa Fe Depot (1926), the Monte Vista Hotel (1926), and many other

historic travel, trade, and social buildings that date from the period between

the late 1880s and the 1940s.

In 1987, the city drafted a

new master plan, also known as the Growth Management Guide 2000, which

transformed downtown Flagstaff from a shopping and trade center into a regional

center for finance, office use, and government.

The city built a new City Hall, Library, and the Coconino County

Administrative Building in the downtown district.

By 1990, Flagstaff’s

population was just under 46,000 people.

During the 1990s, downtown Flagstaff

became more cultural again. Store owners

in downtown supported the Main Street programs of preservation-based

revitalization. Many of the downtown

sidewalks were repaved with decorative brick facing and a different mix of

shops and restaurants opened up to take advantage of the area's historical

appeal. The historic sandstone buildings were restored, and parts of downtown

became targeted towards tourism. After

the Railroad Addition district became protected, and the historic quality of

the city was appreciated by officials, more neighborhoods became registered as

historic districts. Heritage Square was

built as the center of the revitalized downtown, including mapping the history

of the area on various structures. The

local Flagstaff Pulliam Airport began running more flights to

Phoenix, allowing commuting, and the school district was expanded with a third

high school. Microbreweries opened

downtown in the early 1990s, as did craft restaurants.

Brick-lined Heritage Square, designed to accommodate 1,200 people for a performance or just a handful of folks hanging out on a sunny afternoon, surrounded by restaurants, shops, and galleries.

On October 24, 2001,

Flagstaff was recognized by the International Dark-Sky Association for

its efforts in preserving the nighttime environment for astronomy. Flagstaff was designated as the world's first

"International Dark-Sky City,” and in 2012, it was officially named

"America's First STEM Community,” for its work in improving STEM (Science,

Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) education.

Industrial use of the city

grew in the 21st century: SenesTech started in 2004, a major

producer of pest control agents, and was the first publicly-traded company

headquartered in Flagstaff, until it downsized and moved to Phoenix in 2020. The Nestlé Purina Pet Care factory

in East Flagstaff is also a major industry hub. A new industry also sprouted in the 2010s,

with Flagstaff becoming an altitude training destination for elite

athletes. The Hypo 2 High Performance

Sport Center in the city trained over 85 Olympic medalists from 44 countries

between 2012 and 2019.

Flagstaff’s industry and population

have continued to grow through the present time.

Flagstaff Today

Today,

Flagstaff’s population exceeds 75,000 people.

Northern

Arizona University is the city’s largest employer and has a major economic

impact annually. Besides NAU, other major public employers include the

City of Flagstaff, Coconino County, Flagstaff Medical Center, Flagstaff Unified

School District, U.S. Forest Service, and the U.S. Geological Survey. Major private employers include Joy Cone (ice cream cones),

Nestle Purina (pet food), and W. L. Gore and Associates (manufacturing company specializing

in products derived from fluoropolymers). Tourism is also a large employer as the city

sees over five million visitors per year.

Flagstaff’s

Historic District proudly displays its historic buildings that the city went to

so much trouble to save and preserve. The

McMillan Building today contains the McMillan Bar and Kitchen, and other

businesses. The Babbitt Brothers

Building operates today as Babbitts Backcountry Outfitters. The Weatherford and

Monte Vista Hotels are still welcoming overnight visitors. The Orpheum Theater still provides

entertainment. The Santa Fe Depot now

serves as Flagstaff’s Amtrack Station and the city’s Visitors Center.

The history of these Flagstaff buildings was discussed earlier. Can you identify them as they look today?

The Flagstaff Visitors Center provides a brochure and directions

for a walking tour of the city’s historic district.

Flagstaff has an active cultural scene. The city is home to the

Flagstaff Symphony Orchestra, attracts folk and contemporary acoustic musicians,

and offers several annual music festivals during the summer months. Popular bands play throughout the year at the

Orpheum Theater, and free concerts are held during the summer months at

Heritage Square. Beyond music, Flagstaff

has a popular theater scene, featuring several groups. A variety of weekend festivals occur

throughout the year including festivals for books, film, Hopi and Navajo arts

and crafts, beer tasting, and science.

Flagstaff has two world-class museums, the Museum of Northern

Arizona, featuring prehistoric southwest history, and the Lowell Observatory,

containing a wealth of local astronomy history and instruments. Other local museums include the Fort Tuthill

Military Museum, with local National Guard history; the Pioneer Museum, with remnants of northern Arizona's farming and transportation

past; and the art galleries

at the Museum of Northern Arizona.

Flagstaff has acquired a reputation as a magnet for outdoor

enthusiasts, and the region's varied terrain, high elevation, and amenable

weather attract campers, backpackers, climbers, recreation and elite runners,

and mountain bikers from throughout the southwestern United States. There are

679.2 acres of city parks in Flagstaff, the largest of which are Thorpe Park

and Buffalo Park. Wheeler Park, next to City Hall, is the location of summer

concerts and other events. The city maintains an extensive network of trails;

the Flagstaff Urban Trails System includes more than 50 miles of paved and

unpaved trails for hiking, running, and cycling. The trail network extends

throughout the city and is widely used for both recreation and transportation. There are over 56 miles of urban trails in

Flagstaff. The area is a recreational

hub for road cycling and mountain biking clubs, organized triathlon events, and

annual cross country ski races. Several major river running operators are

headquartered in Flagstaff, and the city serves as a base for Grand Canyon and

Colorado River expeditions.

Flagstaff's proximity to Grand Canyon National Park,

about 75 miles north of the city, has made it a popular tourist destination

since the mid-19th century. Other nearby

outdoor attractions include Walnut Canyon National Monument, Sunset

Crater Volcano National Monument, Wupatki National Monument, and Meteor

Crater. Glen Canyon National Recreation Area and Lake

Powell are both about 135 miles north along U.S. Route 89. Sedona, and the red rock country, are just 25

miles south on U.S. 89, via Oak Creek Canyon.

Flagstaff also offers tourists

the 200-acre Arboretum at Flagstaff, home to 750 species of mostly

drought-tolerant native and adapted plants representative of the high-desert Colorado

Plateau.

Numerous Sinagua prehistoric

archeological sites can be visited in the Flagstaff area.

The Yavapai-Apache Nation is

still located in the Verde Valley, comprised of five noncontiguous tribal

communities with 2,596 total enrolled tribal members. About 750 members live in the five

communities.

Since 1851, the Flagstaff area

has been “on the path” of cross-country travelers, from the Sitgreaves

expedition, to Whipple’s expedition, to Beale’s Wagon Road, to the Santa Fe

Railroad, to Route 66, and finally Interstate 40. And more recently, Flagstaff became an

important stop for north-south traffic with Interstate 17, and U.S. Route

89. This history as a transportation

network “node” is represented by a current Flagstaff set of Route 66 road signs

shown below.

Route 66 in Flagstaff, where all major area highways meet.

Comments

Post a Comment