HISTORY42 - Illegal Immigration to the United States

My previous blog article (posted

July 3, 2021) was about the history of legal immigration to America,

covering British Colonial America and the United States of America. This blog article covers the history of illegal

immigration to the United States.

Principle sources for this

article include “Historical Timeline - History of Legal and Illegal Immigration

to the United States,” immigration.procon.org; Pew Research Center; CATO

Institute; U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Customs and Border Protection;

“Illegal Immigration Statistics,” FactCheck.org; “Illegal Immigration in the

United States - Statistics & Facts,” Statista.com; “U.S. Immigration

Trends,” Migration Policy Institute; “Overview of INS History,” U.S. Citizen

Citizenship and Immigration Services; and the Wall Street Journal - supplemented

with numerous other online sources.

To set the context for this

discussion, I want to review a few things from the previous article.

The Pew Research Center reported

that in 2019, of a total U.S. population of 328.2 million, 44.9 million had

immigrated directly from another country.

The figure below shows the yearly number of

immigrants to the U.S. from 1820 to 2015.

These almost 200 years are divided into phases or periods, with the

predominant immigrant origin locations for each phase: Frontier Expansion, Industrialization, The

Great Pause, and Post-1965.

|

| Immigration numbers to the U.S. by year, 1820 - 2015. |

After

the American Revolution and the first United States census in 1790, there was

little immigration to the U.S. from 1790 to 1820, with an estimated average of

only 60,000 immigrants per decade. From

1820 to 1880 was the age of U.S. expansion; by 1880 the U.S. had reached almost

its current geographic size, with a total population of over 50 million

people. A major wave of immigration

occurred during this period, with most immigrants coming from Northern and

Western Europe. The period between 1880

and 1920 was a time of rapid industrialization, and experienced the “great wave

of immigration,” mostly from Southern and Eastern Europe. The period from 1920 to 1965 is called “The

Great Pause,” because immigration dramatically slowed, due to events like the

World Wars, the Great Depression, and for the first time, restrictive

immigration laws. Most immigrants then came

from Western Europe. Immigration picked

up considerably after 1965, with immigration policy permitting greater numbers

of people from Asia and Latin America.

With

this overview as background, I will discuss illegal immigration in these same time

periods, in timeline format, framed by U.S. immigration policy. I’m going to skip the “frontier expansion”

period and start in 1820 with the” industrialization” period, since there was

little immigration earlier. I’ll finish

with a look back at illegal immigration trends and a look ahead to the future.

In

general, illegal immigrants came to the U.S. to flee from insecurity, violence,

and religious or political persecution in their own countries; in search of

better economic opportunities; or to join family already in the U.S.

Until the late 19th

century, there wasn’t any such thing as “illegal” immigration to the United States. That’s because before you can immigrate

somewhere illegally, there has to be a law for you to break.

Industrialization (1880 -1920)

The Chinese were the first people to experience resistance to

immigration to the United States. From

1863 - 1869, the Central Pacific Railroad hired Chinese laborers to construct

the western end of the first transcontinental railroad. Chinese immigration to the U.S continued

between 1870 and 1880; by 1880 the Chinese population totaled about 105,500 out

of the U.S. population of 50 million.

|

| 20,000 Chinese laborers were brought in to help build the first transcontinental railroad, completed in 1869. |

Californians

were upset with Chinese immigrants, who were willing to work for lower wages

than the rest of the population. In response to a remarkable intensity of complaint on the

West Coast, which was increasingly expressed nationwide, Congress moved rapidly

toward a historic reversal of the tradition of laissez-faire in immigration

matters, and by wide margins passed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882,

suspending the admission of Chinese laborers for ten years. It was the first sharp curtailment of

immigration to America and was extended with minor adjustments for sixty years. A new tradition of restricting U.S.

immigration through federal policy had begun.

1882: Chinese Exclusion Act passes and Immigration

Exclusion Era began.

1886

- 1896: Various Supreme Court rulings were

made regarding the Constitutional rights of illegal immigrants, e.g., all

people, regardless of "race, color, or nationality" have the right to

due process and equal protection under the law. Even an

immigrant who had broken immigration law, still had the right to make his case

to a judge before being “deprived of life, liberty, or property.”

1891: Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1891

that established the Bureau of Immigration in the Treasury Department, assuming

direct control of inspecting, admitting, rejecting, and processing all

immigrants seeking admission to the U.S.

The Bureau was empowered to enforce immigration laws and to deport

unlawful aliens. Because most

immigration laws of the time sought to protect American worker and wages, in

1903, the Bureau of Immigration was transferred to the newly created Department

of Commerce and Labor.

1904:

Mounted border watchmen were employed by the U.S. Immigration

Service to prevent illegal southern border crossings, largely pursuing Chinese

immigrants trying to avoid the Chinese exclusion laws. Texas Rangers

were also often employed in border protection. The coast of California was carefully

guarded, hoping to stop illegal Chinese immigrants.

1910 - 1920: Mexican Revolution period. Mexican refugees and dissidents started

flowing north to the U.S.

In the 1910s, tensions from the

Mexican Revolution (1910 - 1920) and World War I (1914 - 1918) undermined

border cooperation between the U.S. and Mexico.

Mexican rebels and federals fought each other in several engagements

along the Arizona and New Mexico borders; the rebels sometimes raided border

towns - resulting in military skirmishes.

U.S. troops and the National Guard reinforced border positions and

patrolled along the border to protect U.S. neutrality. The result of these conflicts was stricter

control of the border and the beginning of permanent fences that bisected

border towns like Nogales.

Large numbers of Mexicans began

coming into the U.S. during and after the Mexican Revolution, looking to escape

military and political turmoil, and tough economic conditions. Significant Mexican migration to the U.S.

continued during World War I to replace American workers who were fighting

overseas.

From its beginning with

rumrunners during Prohibition, and opium smuggling during the 1910s and 1920s,

the smuggling of illegal substances emerged as one of the most significant

border control issues.

1911: The

Dillingham Commission, a bipartisan Congressional committee, formed

to study the origins and consequences of recent immigration to the United

States, defined a difference between "desirable" and

"undesirable" immigrants, based upon ethnicity, race, and religion,

with northern European Protestants being favored over southern or eastern

European Catholics and Jews, with non-European immigrants considered highly

undesirable.

In 1920, the U.S. Bureau

of Immigration estimated that 17,300 Chines entered the U.S. illegally through

Canada and Mexico, since the Passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

The Great Pause (1920 - 1965)

Through 1943, statutes and administrative actions set narrowing

numerical limits for those immigrants who had not otherwise been excluded.

During those years a federal bureaucracy was created to control immigration and

immigrants, a bureaucracy whose initial mission was to keep out, first Chinese,

and then others who were deemed inferior, particularly Mexicans.

1920 - 1933: Illegal entry into the United States became a particular problem

during Prohibition (1920 - 1933), when bootleggers and smugglers would

illegally enter the country to transport alcohol.

1924: The Immigration

Act of 1924 established visa requirements and enacted quotas for immigrants

from specific countries, especially

targeting Southern and Eastern Europeans, particularly Italians

and Jews, and effectively prohibited virtually all Asians from immigrating to

America.

1924: Congress passed the Labor Appropriation Act

of 1924, officially establishing the U.S. Border Patrol for the purpose of

securing the borders between inspection stations. In 1925, its duties were

expanded to patrol the seacoast. Many of

the early agents were recruited from organizations such as the Texas Rangers,

local sheriffs and deputies, and appointees from the Civil Service Register of

Railroad Mail Clerks.

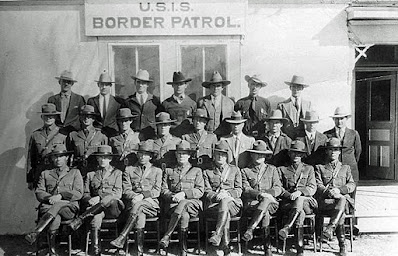

|

| Border Patrol agents, circa late 1920s. |

In 1927, the U.S. Labor Secretary

estimated that there were over

1,000,000 people in the U.S. illegally.

1929:

Congress passed the Undesirable Aliens Act of 1929.

In

the early 20th century, it wasn’t a crime to enter the U.S. without

authorization. Though authorities could deport immigrants who hadn’t gone

through an official entry point, they couldn’t be detained and prosecuted for a

federal crime. But that all changed in 1929 when the U.S. Congress passed a

bill to restrict a group of immigrants it hadn’t really focused on before:

people who crossed the U.S.-Mexican border.

The

Undesirable Aliens Act of 1929 criminalized crossing the southern border

outside an official port of entry, primarily designed to restrict Mexican

immigration. The law made “unlawfully entering the country” a misdemeanor and

returning after a deportation, a felony, punishable

by up to two years imprisonment and $1,000 in fines.

Soon after passage of the Act, the U.S. economy entered the

Great Depression and the federal government coerced Mexicans in the United

States into repatriating by threatening penalties and conducting immigration

raids targeting those who could not prove their legal status. By the end of the

1930s, U.S. attorneys had prosecuted more than 44,000 cases of unlawful entry,

almost entirely against Mexicans.

1933: After two decades as an independent service,

the Bureau of Naturalization was united with the Bureau of Immigration to form

the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), under new Department of

Labor.

1943: Bracero

Program began.

World War II drained enough U.S. manpower to

force Washington to look abroad for recruits to support a wartime economy. The U.S. and Mexico agreed on a special

program that allowed migrant Mexican laborers to work on U.S. farms and railroads. After

having tried to dissuade Mexicans from migrating for half a century, the U.S.

government now began to organize and channel huge numbers of migrant workers - braceros

- across its border. The “Bracero”

program established a “binational collective labor agreement” that over its

21-year operation mobilized more than five million temporary workers, most of

whom worked seasonally, returning to Mexico in the “off season,” and coming

back to the U.S. the next year.

|

| Mexicans signing up for the Bracero Program that allowed Mexican laborers to work on U.S. farms and railroads temporarily during World War II. |

1943: The Chines

Exclusion Act of 1882 was repealed by the Magnuson Act of 1943, which

allowed 105 Chinese to enter per year. Chinese immigration later increased with

the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, which abolished direct racial barriers, and later by the Immigration and Nationality Act of

1965 (see below), which abolished quotas from specific countries.

1964: Bracero Program ended.

Washington cancelled the Bracero program

unilaterally. Mexican migrant laborers

continued to arrive without papers and outside of negotiated agreements. Thus

began the era of undocumented migration by “irregular” migrants who worked

temporarily under the threat of deportation. The Mexican side was a “no-man's

land,” where criminals and human traffickers operated freely. Laissez-faire

attitudes and policies reigned, though both governments would pay the costs 20

years later.

Undocumented immigrants don’t possess a valid visa or other

immigration documentation, because they entered the U.S. without inspection,

stayed longer than their temporary visa permitted, or otherwise violated the

terms under which they were admitted.

1965 - 2006: Legislative Efforts

This

period saw legislative attempts to improve immigration policy. Immigration quotas were abolished and

replaced with overall annual caps on immigration numbers. Discriminatory immigrant preferences were

also abolished. Considerable attention

was paid to reducing illegal immigration, and in some cases, significant

amnesty programs were approved. Annual

unauthorized immigrant entries continued to grow steadily during this period. See the section on “Illegal Immigration

Trends” below.

1965: Immigration

and Nationality Act of 1965 passed.

National-origin

immigration quotas were eased in the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952,

and a year after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed

discrimination based on race or national origin, the Immigration and

Nationality Act of 1965 abolished the quota system. There was, for the

first time, a limitation on Western Hemisphere (the Americas) immigration

(120,000 per year), with the Eastern Hemisphere limited to 170,000. The law changed the preference system for

immigrants, no longer defined by race, sex, gender, ancestry, or national

origin. Specifically, the law provided

preference to immigrants with skills needed in the U.S. workforce, refugees,

and asylum seekers, as well as family members of U.S. citizens. The Immigration and Nationality Act

of 1965 resulted in greatly increased immigration from non-European

countries, particularly Asian and Latin American countries - once again

changing the character of the American population.

U.S. Census estimated 2-4 million

immigrants in the United States illegally in 1980, with about half from Mexico.

1986: Immigration

Reform and Control Act of 1986 set penalties for knowingly hiring illegal

immigrants and granted legal status (amnesty) to 2.7 million immigrants in the

U.S. illegally before January 1, 1982. Despite the passage of the act, the population of illegal

immigrants continued to rise.

1996: President

Bill Clinton signed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant

Responsibility Act of 1996. The key components of the Act included

increasing the number of border agents, increasing penalties on those who

assisted illegal immigrants into the United States, creating a 10-year re-entry

ban on those who had been deported after living in the U.S. illegally for over

one year, and expanding the list of crimes that any immigrant (regardless of

legal status) could be deported for. The

Act also allowed 300,000 Central Americans to become legal residents.

Increased

border militarization in the United States had the unintended consequence of

increasing illegal immigration, as temporary undocumented immigrants who

entered the United States seasonally for work, opted to stay permanently and

bring their families, once it became harder to move across the border

regularly.

2000:

The AFL-CIO Labor Union supported an amnesty program that

would allow undocumented members of local communities to adjust their status to

permanent residents and become eligible for naturalization.

2001: Dream (Development,

Relief, and Education for Alien Minors) Act introduced in Congress to grant

temporary, conditional residency, with the right to work, to unauthorized

immigrants who entered the United States as minors - and if they satisfied

further qualifications, would attain permanent residency. The bill did not pass and has been since

introduced several times without passing.

2001-2003:

Immigration numbers dropped precipitously as a direct result of the

terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, but began rising again thereafter.

2002: The

Department of Homeland Security (DHS) was founded with emphasis on

border security and removing criminal aliens to protect the nation from

terrorist attacks. The United States

retained its commitment to welcoming lawful immigrants and supporting their

integration and participation in American civic culture. The Homeland

Security Act of 2002 disbanded the Immigration and Naturalization Service. Its constituent parts contributed to three

new federal agencies: 1. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), 2. Immigration

and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and 3. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

(USCIS). CBP prevents drugs, weapons, and terrorists and other inadmissible

persons from entering the country. ICE enforces criminal and civil laws

governing border control, customs, trade, and immigration. USCIS oversees

lawful immigration to the United States and naturalization of new American

citizens.

|

| President George W. Bush signing the Homeland Security Act of 2002. |

2005: President George W. Bush’s Secure

Border Initiative was announced - a comprehensive multi-year plan to

secure America's borders and reduce illegal migration. The initiative included more agents to patrol

our borders, secure our ports of entry, and enforce immigration laws, including

expanded detention and removal capabilities to eliminate “catch and release”

once and for all; a comprehensive and systemic upgrading of the technology used

in controlling the border, including increased manned aerial assets, expanded

use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, and next-generation detection technology;

increased investment in infrastructure improvements at the border - providing

additional physical security to sharply reduce illegal border crossings; and

greatly increased interior enforcement of our immigration laws – including more

robust worksite enforcement.

2005: The Minuteman

Project was founded by a group of private individuals who sought to

extrajudicially monitor the United States - Mexico border's flow

of illegal immigrants. The Minuteman

Project also created a political action committee which lobbied for representatives who

supported proactive immigration law enforcement and focused on resolving border

security issues. They strongly supported building a wall and placing additional

border patrol agents or military personnel on the Mexico - United States

border in order to curb free movement across it. Roughly half of the

Minuteman Project's members strongly opposed amnesty as well as

a guest worker program, and an overwhelming number of them opposed sending

funds to Mexico in order to pay for the improvement of its infrastructure.

2005: The REAL ID

Act of 2005 changed some visa limits, tightened restrictions on asylum

applications and made it easier to exclude suspected terrorists, and removed

restrictions on building border fences.

2006: The Secure

Fence Act of 2006 was signed into law. The Act authorized the

construction of 700 hundred miles of double-layered fencing along the nation's southern

border with Mexico. It also directed the Secretary of Homeland Security to take

action to stop the unlawful entry of undocumented immigrants, terrorists, and

contraband into the U.S., using both personnel and surveillance technology.

2006 - Present: Executive Orders - Turmoil

With

illegal immigration the major issue, this period - spanning the administrations

of Presidents Barack Obama and Donald Trump, and the start of President Joe

Biden’s presidency - was unfortunately beset with polarizing political disagreements

that continue today. No Congressional

agreements were reached on meaningful immigration legislation and each

president resorted to executive orders to achieve his own “progress.” In addition, there was considerable activity in

some of the states of the union to instigate local immigration policy, often in

direct conflict with federal policy, including setting up so-called sanctuary

cities that limit cooperation with the national government’s effort to enforce

immigration law. Other significant (and

unresolved) issues include migrant caravans from Central America; unaccompanied

minors; detention policy at the U.S. - Mexico border, such as facilities,

family separation, and time of detention; and illegal immigrant crime,

especially by those previously deported and reentered illegally. Ironically, amidst the turmoil, the unauthorized

immigrant resident population peaked, started to decline, and stabilized during

this period. See the next section on “Illegal

Immigration Trends.”

The table below shows immigration activities during the administrations of Presidents Obama, Trump, and Biden.

Immigration activity from 2009

to the present, during the administrations of Presidents Obama, Trump, and

Biden.

|

Time Period

|

Immigration Issue |

Activity |

|

2009-2017 Obama Administration |

U.S. State Initiative

|

Arizona passed law expanding state authority to

combat illegal immigration (2010).

U.S. Supreme Court upheld key provision, but blocked parts on grounds

they interfered with fed’s role in setting immigration policy (2012). |

|

Secure Border Initiative

|

Homeland Security Secretary cancelled Initiative in

force since 2005 (2011). |

|

|

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) |

Homeland Security allowed some undocumented

immigrants, who came to the U.S. as children, to stay in country (2012). |

|

|

Deportation

|

Executive action to prevent deportation of 4.7

million undocumented immigrants in U.S. illegally (2014). |

|

|

2017-2021 Trump Administration |

Border Wall

|

Executive Order to increase Border Patrol forces and

begin building border wall (2017). |

|

Foreign Entry/Travel

|

Executive Order suspending entry of terrorist-risk

(mostly Muslim) countries and all refugees (2017). Executive Order restricting travel in U.S.

for selected countries based on national security considerations (2017). Supreme Court upheld travel ban (2018). |

|

|

DACA

|

Ended DACA program (2017). Supreme Court disallowed, keeping DACA in

place (2020). |

|

|

U.S. State Initiatives

|

California became sanctuary state, vastly limiting

cooperation with federal immigration authorities (2017). California became first state to extend

Medicaid to undocumented immigrants (2019). |

|

|

Detention at Border

|

Supreme Court ruled undocumented immigrants can be

detained indefinitely (2018). |

|

|

U.S. - Mexico Agreement

|

Mexico agreed to increase border enforcement at

sites of Central American migrant entry and to support retention in Mexico of

asylum seekers awaiting decision on U.S. entry (2019). |

|

|

COVID-19

|

Executive Order temporarily suspending all

immigration during COVID-19 pandemic (2020). |

|

|

Citizenship Requirements

|

Updated number and complexity of questions for U.S.

citizenship (2020). |

|

|

2021- Biden Administration |

Deportation

|

Paused most deportations for 100 days (2021) |

|

Travel Bans

|

Revoked travel bans from primarily Muslim and

African countries (2021). |

|

|

Border Wall

|

Halted border wall construction (2021). |

|

|

DACA

|

Extended DACA (2021). |

|

|

Border Retention

|

Ended Trump’s Zero Tolerance policy requiring

prosecution of all adults crossing southern border illegally (2021). |

Illegal Immigration Trends - Looking Back

The figure below summarizes

illegal immigration since 1990.

The number of unauthorized immigrants

residing in the U.S. rose steadily from 3.5 million in 1990 to a peak of 12.2

million in 2007, after which the unauthorized immigrant population started to

decline as shown in the top panel of the figure. The decrease was mainly due to a decrease in people

from Mexico.

The middle panel shows that since about 2016,

Mexicans are no longer the majority of unauthorized immigrants living in the

U.S. The population of Mexican-born unauthorized immigrants

declined after 2007 because the number of newly arrived unauthorized immigrants

from Mexico fell dramatically - and as a result, more left the U.S. than

arrived.

As the bottom panel shows, most Mexican

unauthorized immigrants are now long-term residents.

Total arrivals in the U.S. of undocumented people

from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras remained at about the same level in

2018 as in the previous four years.

The next figure shows the numbers of

unauthorized residents for 2018, breaking down the numbers from each country of

origin. Mexico had about 47% of

unauthorized residents. Central America,

including El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, totaled about 16%.

Immigration to the U.S. from India started with small numbers in the early 19th century, to communities along the West Coast. Although their presence remained small, Indian resident numbers grew tremendously from about 200,000 in 1980 to 2.5 million in 2018. Of that number, about 540,000 were unauthorized, representing 4.7% of the undocumented population, exceeding China’s 3.6%.

Counting

unauthorized arrivals each year is difficult; officials need time after the

fact to evaluate local population characteristics and do detailed analysis of

census records. Border apprehension of

illegal immigrants is one measure authorities use to gauge illegal entry

activity. The figure below shows

apprehension data for the southwest border from 1961-2018.

|

| Border apprehensions are one measure of illegal entry activity. |

Illegal immigration across the U.S. - Canadian border is much less than that for the southwest border with Mexico (hundreds annually, compared to over a million in some years), but nearly tripled between 2016 and 2019. According to federal data, a growing portion are Mexican citizens, who find it easier to cross the northern border. The Urban Institute estimates that between 65,000 and 75,000 Canadians currently live illegally in the United States.

Overall,

border apprehensions dropped considerably during the administrations of

Presidents Obama and Trump, reflecting the overall decrease in unauthorized

immigrants residing in the U.S.

Since

2010, about two-thirds of undocumented new arrivals have overstayed temporary

visas and one-third entered illegally across the border.

Looking Ahead

Adapted

from a CATO Institute 2020 white paper: Congress has

repeatedly considered and rejected comprehensive immigration reform legislation

over the past few decades. Those failed

immigration reforms all included three policies: legalize illegal immigrants

currently living in the United States, increase border and interior enforcement

of the immigration laws, and liberalize legal permanent immigration and

temporary migration through an expanded guest worker visa program for

lower‐skilled workers. Domestic amnesty

for illegal immigrants would to allow those, who have made a life here, to

settle permanently; extra enforcement would reduce the potential for illegal

immigrants to come in the future; liberalized immigration would boost U.S.

economic prosperity and drive future would‐be illegal immigrants into the

legal market.

A 2019 Gallup poll found

that 76% of Americans considered immigration a good thing for the United

States. As many as 81% supported a path to citizenship for undocumented

immigrants if they meet certain requirements. A 2016 Gallup

poll found that among Republicans, support for a path to citizenship (76%)

was higher than support for a proposed border wall (62%).

With

so much agreement, it’s frustrating that we as a nation have not been able to

improve out immigration policy.

Congressional attempts have fallen to politics and special

interests. Executive orders and

proclamations are short lasting, and as we have seen, a president of one party

immediately throws out the products of the other party - leaving the country in

a constant state of immigration turmoil.

We should be ashamed!

I’ll

close with a quote from a Wall Street Journal article:

Modern opposition to immigration is for the most part not to immigration per se, nor to particular ethnic groups, as it was in the past, but to the perception that illegal immigration has undermined the rule of law.

Comments

Post a Comment