HISTORY40 - Photography

This article is about the history

of photography. For my purposes,

photography is the process of creating durable images by recording light,

either chemically, by means of a light-sensitive material, such as photographic

film, or electronically, by means of an image sensor. The word “photography” was created from the

Greek roots of two words that combined mean “drawing with light.”

Note: Photography has been an important part of Ring-family life for 116 years. In 1905, my Grandfather Ambrose Ring began taking photos of his mining exploits in southern Arizona. In the 1990s, my brother Al Ring and I (re)discovered these old prints, started exploring where the images were taken, and began research about the mining history of the region. Our research culminated in the publication of the book, “Ruby Arizona - Mining, Mayhem, and Murder,” in 2005. This history of a borderland mining ghost town, set us off on a (retirement) career of Arizona historical research and writings that included newspaper columns, additional books, and a dedicated website (ringbrothershistory.com). Pat and I continue the Ring-family photography tradition today by recording family events and exploring creativity in making interesting pictures.

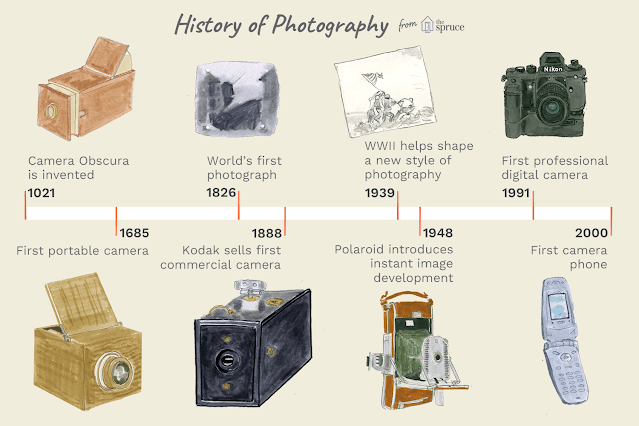

The history of photography began

in remote antiquity with the discovery of two critical principles: pin-hole

image projection and the observation that some substances are visibly altered

by exposure to light. The birth of

photography was then concerned with inventing means to capture and retain

images - an invention that did not occur until the 1820s.

This article will cover

photography’s enabling principles, the quest for permanent images, early camera

improvements, popularization of photography, instant photos, influence of WWII

photography, advanced image control and smart cameras, digital photography, and

the future of photography.

The Phenomenon of Camera

Obscura

A natural phenomenon, known as camera obscura, or

pinhole image, can project an image through a small opening in one surface onto

an opposite surface. This principle may

have been known in prehistoric times, but the earliest known written record of

the camera obscura effect is to be found in Chinese writings dated to the 5th

century BC. For the next 1,500 years or

so, various scientists observed the camera obscura effect and conducted

experiments to better understand the behavior of light. The first person to suggest that an image

from one side of a hole in a surface could be projected onto a screen on the

other side of the surface, and prove the concept, was Iraqi scientist Ibn al-Haytham, in his Book of Optics in 1021. Ibn al-Haytham, known as the “father of modern

optics,” is credited with the invention of the camera obscura.

The camera obscura (Latin for “dark

chamber) consists of a dark room, tent, box, etc., with a small hole in one of

the walls (or the ceiling). The light passing through the small hole will

project an image of the scene outside the chamber onto a surface in the chamber

opposite to the hole. Since light moves

in a straight line (first law of geometric optics) through the hole, the

projected image will appear to be flipped (upside-down) and reversed (left-to-right), but with color

and perspective preserved.

The figure below illustrates the

camera obscura effect.

This diagram illustrates the phenomenon of camera obscura.

The

light from the top of the candle travels down through the hole to the bottom of

the wall opposite. Similarly, the light from the bottom of the candle appears

projected at the top of the wall inside the box, making the image appear upside

down. Similarly, the image is also inverted,

or reversed, left-to-right.

Camera obscuras were used in 13th

century for safe observation of solar eclipses, without having to look directly

at the sun. At the same time, the effect

was used as a projector for entertainment. Artists started using camera obscuras in 15th

century.

Artist using a room-size camera obscura.

In the 17th century, portable versions of the

camera obscura were developed and commonly used - first as a tent, later as

boxes. In

1685, the first portable box camera obscura that was small enough for practical

use was built by German author Johann Zahn. Basic lenses to focus the light and provide a

larger aperture, compared to the pinhole, were also introduced around this

time.

The

box-type camera obscura often had a 45-degree angled mirror projecting an

upright image onto tracing paper placed

on the box’s glass top, restoring the scene’s original up-down, right-left

projection. Artists

discovered this phenomenon and used it to help them create (tracing, drawing,

and painting) realistic images of the outside world on a two-dimensional

surface.

A camera obscura box with an internal mirror, projecting an upright image at the top.

Note: The human eye (and those of animals

such as birds, fish, reptiles, etc.) works much like a camera obscura, with a

small opening (pupil), a convex lens, and a surface where the image is

formed (retina). The human brain

provides the geometric translation to preserve the original scene’s up-down,

right-left arrangement.

The camera obscura concept was

developed further into the photographic camera in the first half of the

19th century, when camera obscura boxes were used to expose light-sensitive

materials to the projected image.

Light Sensitive Materials

The

notion that light can affect various substances - for instance, the sun tanning

of skin or fading of textiles - has been around since very early times, but it

was not until the late Middle Ages that light sensitive material critical to

photography would be discovered.

German Friar Albertus Magnus discovered silver nitrate in the

13th century, while German poet, historian, and archaeologist Georg Fabricius

discovered silver chloride in the 16th century. These chemicals were observed to be sensitive

to light (becoming black on exposure to light), but were not applied to

photography for many years, despite early knowledge of the camera obscura.

In

1777, Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele was studying the more

intrinsically light-sensitive silver chloride and determined that

light darkened it by disintegrating it into microscopic dark particles of

metallic silver. Of greater potential

usefulness, Scheele found that ammonia dissolved the silver chloride,

but not the dark particles. This discovery could have been used to stabilize or

"fix" a camera image captured with silver chloride, but was not

picked up by the earliest photography experimenters. Scheele also noted that red light did not have

much effect on silver chloride, a phenomenon that would later be applied in

photographic darkrooms as a method of seeing black-and-white prints

without harming their development.

First Permanent Images

Around

the year 1800, British inventor Thomas Wedgwood made the

first known attempt to capture an image in a camera obscura by means of a

light-sensitive substance. He used paper

or white leather treated with silver nitrate. His experiments yielded only faint images that

were not light-fast, but his conceptual breakthrough and partial success have

led some historians to call him "the first photographer.”

In 1816, French inventor Nicephore Niépce began experiments trying to produces permanent images with a camera obscura. His initial efforts with silver chloride failed, so he turned his attention to light-sensitive organic substances.

The oldest surviving photograph of an image formed in a camera was created by Niépce in 1826 or 1827. It was made on a polished sheet of pewter, and the light-sensitive substance was a thin coating of bitumen, a naturally occurring petroleum tar, which was dissolved in lavender oil, applied to the surface of the pewter and allowed to dry before use. After a very long exposure in the camera (traditionally said to be eight hours, but now believed to be several days), the bitumen was sufficiently hardened in proportion to its exposure to light that the unhardened part could be removed with a solvent, leaving a positive image with the light areas represented by hardened bitumen and the dark areas by bare pewter. To see the image plainly, the plate had to be lit and viewed in such a way that the bare metal appeared dark and the bitumen relatively light.

The world's oldest surviving photograph, a view outside the window of French photographer Nicephore Niépce, 1826 or 1827.

In partnership, Niépce and fellow

Frenchman Louis Daguerre refined the bitumen process, substituting a

more sensitive resin and a very different post-exposure treatment that yielded

higher-quality and more easily viewed images. Exposure times in the camera,

although substantially reduced, were still measured in hours.

Daguerreotypes. Niépce died suddenly in 1833,

leaving his notes to Daguerre. More interested in silver-based processes than

Niépce had been, Daguerre experimented with photographing camera images

directly onto a mirror-like silver-surfaced plate that had been exposed to iodine vapor,

which reacted with the silver to form a coating of silver iodide. As with the bitumen process, the result

appeared as a positive (image showing lights and shades or colors true

to the original) when it was suitably lit and viewed. Exposure times were still impractically long

until Daguerre made the pivotal discovery that the non-visible image produced

on such a plate by a much shorter exposure could be "developed" to

full visibility by mercury fumes.

This brought the required exposure time

down to a few minutes under optimum conditions. A strong hot solution of common salt served to

stabilize, or fix, the image by removing the remaining silver

iodide.

On January 7, 1839, this first

complete practical photographic process was announced at a meeting of the

French Academy of Sciences, and the news quickly spread. Known as the daguerreotype process,

it was the most common commercial process until the late 1850s, when it was

superseded by the collodion process.

Emulsion Plates. The collodion (or wet plate) process was named after collodion, a

light-sensitive syrupy emulsion solution of nitrocellulose in a mixture of

alcohol and ether, that was used to coat the photographic material. The process was less expensive than

daguerreotypes and required only two or three seconds

of exposure time, but required the photographic material to be coated with

collodion, sensitized, exposed, and developed within the

span of about fifteen minutes. This

timeline necessitated a portable darkroom for use in the field. Photographers needed

to have chemistry on hand and often traveled in wagons that doubled as a

darkroom. Many photographs from the

Civil War were produced on wet plates.

Collodion could

also be used in dry form, at the cost of greatly increased exposure time. This made

the dry form unsuitable for the usual portraiture work of most professional

photographers of the 19th century. The use of the dry form was

therefore mostly confined to landscape photography and other

special applications, where minutes-long exposure times were tolerable.

Dry Plates. In the 1870s, photography took another huge

leap forward. English photographer and physician

Richard Maddox invented lightweight gelatin negative

plates that were nearly equal to wet plates in speed and quality.

These dry plates

could be produced and stored for later use, rather than made as needed during

the photo-taking process. This allowed photographers much more freedom in

taking photographs. The process also allowed for smaller cameras that could be

hand-held.

Early Camera Improvements

In the mid-1850s, bellows

were added to cameras to help with focusing by changing the distance between

the aperture and the image plate.

As exposure times

decreased, the first camera with a mechanical shutter was developed in the

1880s.

Popularization

The

daguerreotype proved popular in response to the demand

for portraiture that emerged from the middle classes during the

second half of the 19th century. This demand, which could not be met in volume

and in cost by oil painting, added to the push for the commercial development

of photography.

In

1884, George Eastman, of Rochester, New York, developed dry gel on

paper, or film, to replace the photographic plate so that a photographer

no longer needed to carry boxes of plates and toxic chemicals around.

The

flexible roll film allowed Eastman to develop a self-contained wooden box camera that

held 100 film exposures that gave circular images of 2 5/8-inch diameter. The

camera had a small single lens with no focusing adjustment. After taking a photograph, a key on top of the camera was

used to wind the film onto the next frame. There was no viewfinder on the

camera; instead, two V-shaped lines on the top of the camera were intended to

aid aiming the camera at the subject.

In

1888, Eastman's Kodak camera went on the market. The original camera sold for $25, loaded with

a roll of film, and included a leather carrying case. Now anyone could take a photograph and leave

the complex parts of the process to others.

The first Kodak camera designed for the public hit the market in 1888.

Photography became available for the mass-market in 1901 with the introduction of the Kodak Brownie, a long-running popular series of simple and inexpensive cameras. It was a basic box camera with a simple lens that took 2 1/4-inch square pictures. Because of its simple controls and initial price of $1 (equivalent to $31 in 2020), along with the low price of Kodak roll film and processing, the Brownie became very popular.

The

consumer would take pictures and send the camera back to the factory for the

film to be developed and prints made, much like modern disposable cameras. This was the first camera inexpensive enough

for the average person to afford.

Snapshot photography became a national craze. By 1898, just ten years after the first Kodak camera

was introduced, one photography journal estimated that over 1.5 million

roll-film cameras had reached the hands of amateur shutterbugs.

Cameras

and photography continued to evolve. Kodak

soon added optical viewfinders to their cameras. In 1898, Kodak introduced the first pocket folding

camera, and came out with an improved model in 1903 that was produced through

1915. In 1912, Kodak introduced a small

vest pocket camera. In 1925, Leica

introduced the 35 mm format to still photography. In 1932, Kodak introduced the first 8 mm

amateur motion picture film, cameras, and projectors. In 1936, the German company IHAGEE introduced

the first 35 mm Single Lens Reflex camera that

permitted the photographer to view through the lens and see exactly what would

be captured in the image. The popular Kodak Brownie series continued to

be improved and was manufactured until 1986.

My grandfather used a Kodak No. 3A Folding Pocket Camera like this one to take photos of mining activity in the western U.S.

Camera manufacturers gradually added capability for basic image control, including capability to set the camera aperture, shutter speed, and exposure time.

The

first widely used method of color photography was

the Autochrome plate, a process inventors and brothers Auguste

and Louis Lumière began working on in the 1890s and commercially

introduced in 1907. But the process was

complex and expensive. It wasn’t until the 1930s that film was

sensitive enough for hand-held snapshot-taking; color photos served a niche

market of affluent advanced amateurs.

A

new era in color photography began with the introduction

of Kodachrome film, available for 35 mm slides in 1936. It captured the red, green, and blue color

components in three layers of emulsion.

In

1942, Kodacolor film was introduced - the first roll film for snapshots that

yielded negatives for making color prints on paper. Kodacolor was not available in 35 mm cameras

until 1958.

War Photography

Around 1930, Henri-Cartier Bresson and other photographers began

to use small 35 mm cameras to capture images of life as it occurred, rather

than staged portraits. When World War II started in 1939, many photojournalists

adopted this style.

The posed portraits of World War I soldiers gave way to graphic

images of war and its aftermath. Images

such as Associated Press photographer Joel Rosenthal's photo, Raising

the Flag on Iwo Jima, brought the reality of war home and helped

galvanize the American people like never before. This style of capturing

decisive moments shaped the face of photography forever.

Joel Rosenthal's photo, Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima, an example of capturing decisive moments, shaped the face of photography forever.

Instant Images

The

invention of commercially viable instant cameras, which were easy to use, is

generally credited to American scientist Edwin Land, who

unveiled the first commercial instant camera, Polaroid’s Model 95 Land

Camera, in 1948. The Model 95, used a

secret chemical process to develop film inside the camera in less than a

minute.

This

new camera was fairly expensive, but the novelty of instant images caught the

public's attention. By the mid-1960s, Polaroid had many models on the market

and the price had dropped so that even more people could afford it.

In

2008, Polaroid stopped making their famous instant film, and took their secrets

with them.

Polaroid introduced the Model 95 instant image Land Camera in 1948.

Advanced Image Control and Smart

Cameras

While

the French introduced the permanent image, the Japanese brought easier image

control to the photographer.

In

the 1950s, Asahi (which later became Pentax) introduced the Asahiflex camera and

Nikon introduced its Nikon F camera. These were both Single Lens Reflex (SLR) cameras

and the Nikon F allowed for interchangeable lenses and other accessories.

For

the next 30 years, SLR-style cameras remained the camera of choice for serious

photographers. Many improvements were

introduced to both the cameras and the film. Image control in these cameras

grew to include settings for film sensitivity, white balance, clarity,

contrast, brightness, saturation, and hue.

In

the late 1970s and early 1980s, compact cameras that were capable of making basic

image control decisions on their own were introduced. These "point-and-shoot"

cameras calculated shutter speed, aperture,

and focus, leaving photographers free to concentrate on composition. Automatic

cameras became immensely popular with casual photographers.

Simple,

inexpensive disposable cameras were introduced in the mid-1980s and continue to

be popular today. Photographers can

capture moments of most value to them, such as weddings, and mail in the camera

for photo processing.

Professionals

and serious amateurs continued to prefer to make their own adjustments and

enjoyed the image control available with SLR cameras.

Digital Photography

Digital

photography uses an electronic image sensor to record the image as a

set of electronic data rather than as chemical changes on film.

The charge-coupled

device (CCD) was the image-capturing component in first-generation

digital cameras. A CCD is a light sensor that sits behind the camera lens and

captures the image, essentially taking the place of the film in the

camera. It was invented

in 1969 by Willard Boyle and George E. Smith at

AT&T Bell Labs as a memory device. It was Dr. Michael

Tompsett from Bell Labs however, who discovered that the CCD

could be used as an imaging sensor. After

years of use, the CCD has increasingly been replaced by CMOS, complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor technology, that emerged as an alternative to

CCD image sensors and eventually outsold them by the mid-2000s. (Too

complicated to explain here.)

Photography infrastructure

additions helped make digital photography more efficient and easier to

share. JPEG standards were created for

digital images in 1988. Mosaic, the

first web browser that let people view photographs over the web, was released

by the National Center for Supercomputing Applications in 1992.

Today,

digital photography is used by billions of people worldwide, dramatically

increasing photographic activity and material and also fueling citizen

journalism. The web has been a

popular medium for storing and sharing photos ever since the first photograph

was published on the web in 1992.

Since then, sites and apps such

as Facebook, Flickr, Instagram, Imgur, and Photobucket have

been used by many millions of people to share their pictures.

Here

are a few benefits of digital photography over film photography:

a. Photo resolution, even in point-and-shoot

cameras, is often 12-20 megapixels - high enough for large prints. Can choose images to print. Can print any desired size - at home or at a photo

lab.

b. Can change “film” speeds between individual

shots.

c. Digital cameras are generally lighter than

film cameras.

d. Memory cards are tiny and can store many

images.

e. Images can be viewed immediately and then

retaken, or adjusted, if necessary.

f.

Images can be

viewed on a large-screen TV.

g. Images can be edited right on the camera, or

easily processed with photo-editing software.

h. Many cameras offer built-in filters.

i.

No cost for film

or developing. Rechargeable battery

packs are economical.

Digital photography dominates the 21st century. More

than 99% of photographs taken around the world are through digital cameras,

increasingly through smartphones.

Digital

Cameras. In 1981, Sony unveiled the first

consumer camera to use a CCD for imaging, eliminating the need for

film: the Sony Mavica. While the Mavica saved images to disk, the images

were displayed on television, and the camera was not fully digital.

The

first digital camera to both record and save images in a digital format was the

Fujix DS-1P created by Fujfilm in 1988.

In the 1980s and 1990s, numerous manufacturers worked on cameras

that stored images electronically, starting with basic point-and-shoot cameras.

Today, even the most basic

point-and-shoot digital cameras take high quality images.

By 1991, Kodak had produced the first digital camera that was

advanced enough to be used successfully by professionals: the DCS

100, the first commercially available digital Single Lens Reflex camera. Although its high cost precluded uses other

than photojournalism and professional photography, commercial digital

photography was born.

First professional digital camera, the Kodak DCS 100, was introduced in 1991.

Other manufacturers quickly followed and today Canon, Nikon,

Pentax, and other manufacturers offer advanced digital SLR (DSLR) cameras.

In

2008, the first mirrorless camera, the Panasonic Lumix DMC-G1, was released in Japan. Mirrorless

cameras are the latest in professional cameras - they are basically more

compact DSLRs, without the internal mirror that reflects light onto the sensor. Mirrorless cameras are smaller and lighter

than DSLRs with optical capabilities rapidly approaching DSLRs.

In the last 10 years or so, there has been a lot of

development of reduced-size sensors that achieve picture quality approaching

that of so-called “full frame” sensors by virtue of advanced electronic design

and increased computational power.

Examples of this are the “four thirds” sensor and more recently popular

“micro four thirds” sensors that greatly reduce size and weight of mirrorless

cameras.

The

Camera Phone. The big digital revolution was the

camera phone. The Kyocera Visual Phone VP-210, in 1999, and the Samsung

SCH-V200, in 2000, were the first camera phones. A few months later, the Sharp Electronics

J-SH04 J-Phone was the first that didn't have to be plugged into a computer. It could just send photos, making it hugely

popular in Japan and Korea. By 2003,

camera phone sales overtook digital cameras.

One of the first camera phones, the Samsung SCH-V200, introduced in 2000.

In 2007, Apple launched the iPhone, and the smartphone age truly began. The cameras built into phones quickly improved, but a number of factors combined to transform everyone into a photographer: phone memories got bigger so you could take more pictures; CCD sensors were replaced by CMOS chips that use less power; 3G, 4G and 5G made it possible to share photos instantly; and photography sites like Flickr soon gave way to social networks like Facebook and Instagram as a place to share shots.

Today's best camera phones routinely come with two,

three or four cameras to capture even better images. Smartphones' computer

power has also grown rapidly to keep up with improving lenses and image

sensors. If you shoot in “burst” mode,

you can take several photos at a set interval (for example of a moving child),

and later choose the best one to keep.

In addition, today’s camera phones offer good quality video. You can even look through the video, frame by

frame, and choose a frame for a still photo.

Camera phones are rapidly replacing traditional point-and-shoot camera.

Image

Processing. An important difference between digital and

chemical photography is that chemical photography resists photo

manipulation because it involves film and photographic

paper, while digital imaging is a highly manipulative medium. This difference

allows significant post-processing opportunities for digital images.

In

the 1980s, photo editing computer programs for personal

computers were introduced. The first version of Adobe

Photoshop was released in 1987. Since then, with continual updates, it has

become one of the most popular photo editing programs. It is so popular that many people now use the

word "photoshop" to mean photo editing in general.

Adobe

Photoshop Elements, released in 2001, is a graphics editor for

photographers, image editors, and hobbyists. It contains most of the features of Adobe

Photoshop but with fewer and simpler options. The program allows users to

create, edit, organize, and share images.

In

2008, another powerful post-processing software program, Adobe Lightroom, was developed

by and for photographers, to supplement the much more complex Adobe

Photoshop. In Lightroom, you can

both organize your photo library and edit photos. Using Lightroom,

you can easily create image collections, keyword images, share images directly

to social media, batch process, and more.

These

photo-editing programs provide tools for such functions as cropping, resizing,

red eye removal, teeth whitening, straightening, spot healing, erasing, and

painting. They also allow the user to

make adjustments in such image characteristics as white balance for temperature

and tint for correct colors, exposure, contrast, clarity, color saturation,

sharpening for contrast control in light-meets-dark areas, noise reduction,

lens correction, perspective correction, grain for creative effect, vignette

for edge darkening or brightening, radial filter for photo oval-area selection,

graduated filter for rectangular-area selection, brush tool to “brush” on

changes with a mouse or pen/tablet, and HSL to fine tune color properties.

In

2011 the first photo editing mobile apps were released on the

online App Store. The first was Fotolr

Photo Editor. Many, many other apps have been made for other mobile

operating systems. These apps allow easy

editing and photo sharing by tablet computers and smartphones.

Future of Photography

Here are five predictions for the future

of photography from expert Craig Hull in Photography News.

Smartphones Will Kill Off Compacts. Since 2010, digital camera sales have fallen 80%. Where digital camera systems fail, smartphones

will pick up the slack. The rise

of smartphones will continue to bring many advancements: better sensors, higher resolutions, and

intuitive concepts. These will allow

people to take better pictures more easily. After all, the best camera is the

one you have with you. Smartphones

already have constant connectivity, enabling the user to share images

instantly. For most people, a smartphone

does everything that they need. On top of that, there are hundreds of apps to

use. Compact cameras will no longer

provide anything that the smartphone can’t do better.

Death of the DSLR? Over recent years, mirrorless cameras have

improved beyond all predictions. Every

major camera manufacturer now has mirrorless systems. The advantages of these systems over DSLRs,

are they are smaller, lighter, and thus, way more portable. On top of this, the lack of a mirror means

true silent shooting, less camera shake, and a faster rate of continuous burst

shooting. DSLRs had the edge in image

quality, but that gap has now closed.

The Sony A7 RIII mirrorless camera has a full frame sensor and 42.4

effective megapixels. The highest resolution from any DSLR in the world comes

with the Canon EOS 5DS at 50.6MP.

Mirrorless cameras can’t compete on battery life, but that’s just a

matter of time. Slowly, mirrorless

cameras will continue to pick up the slack. We’ll see a slow but sure

shift to the smaller, cheaper models.

Constant Connectivity. Today you can only wirelessly transfer Jpgs,

not Raw. The speeds are slow and you are

limited by distance. These problems

won’t exist forever. Imagine not needing

a memory card for your camera. This

would allow camera manufacturers to make smaller systems. It also saves you money and means you are no

longer limited to 8, 16, 32, 64 or 128 GB.

After

perfecting this technology, next to come will be wireless charging. Imagine a camera that isn’t limited to

batteries or the maximum power they hold.

A portable battery pack could allow you to shoot for days, not hours.

The technology exists for smartphones, so it’s only a matter of time.

Immersive

Photography. What is to stop us from capturing objects to

allow us to see it from all sides. We

already have this technology with 360-degree product images. Sneakers float and rotate in a white

space. You can walk around a statue, as

if you would in real life. You can spin, zoom and move around at your own

leisure. This technology isn’t new. Google

has been using 3D technology for its Google Maps and Earth for a while now.

Attach

these images and concept to a Virtual Reality headset and what do you

have? Something between the Matrix and

the Metaverse. An immersive idea where

you could actually see and touch said statue, building, city. Looking at a family photograph is a

great way to reminisce over past memories. But what if you could walk around

the image as if suspended in time.

Digital

sensors will only grow (albeit with limitations). They will provide us with

more and more detail in larger resolutions. Processes like these are quite lengthy to

capture and process. As technology gets better, the time spent will also

reduce. An image holding a terabyte of

information is not a million miles away.

Immersive photography technology will enable us to see/experience objects and scenes from all sides.

AI Will Change Everything. We already covered photographs creating a 3D world that would be completely immersible. AI (Artificial Intelligence) is what we have to thank for this technology. In the future, we will see AI take over a lot of our photographic tasks. We could all enjoy better, faster and more intuitive autofocusing. Imagine entire scenes and subjects, captured with a perfect exposure automatically.

Not

only will we see improvements with our cameras, but also, with our computers

and image editing software. Machines

will improve and software will recognize every element in your scene. If

it knows what it is, it can act accordingly.

Once

AI becomes well implemented, time spent editing will reduce. Imagine your uploaded photographs

automatically cull themselves, leaving you with the best shots. Then you don’t

need to go through hundreds of images to find where the person’s eyes are open.

On top of selecting these images, applied adjustments will base themselves on

previous behavior. That’s the benefit of AI, it learns from your choices.

Comments

Post a Comment