HISTORY29 - Maps

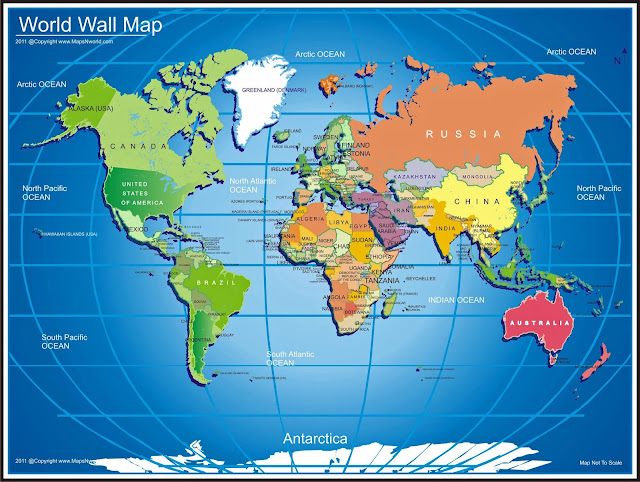

This article is about the history of map making or cartography. Over the last 15 years, I’ve been writing about the history of my hometown Tucson, the state of Arizona, the United States, North America, and much of the rest of the world. Maps have been key to my research and writing; I now really appreciate the relationship of maps to the history of the world. I also have been personally passionate about maps for many years. So, I concluded that it was time to talk about maps, and their history.

Maps have been used for thousands of years for many different purposes including helping ancient man grasp the idea of an unknown world, with himself at the center; plotting the location of towns and objects in one’s local area, then extending to much larger areas as knowledge of other places on earth expanded, sometimes augmented with the tales of travelers; early Christian maps that showed how the story of Christ penetrated the world; navigation for sea voyages, aiding exploration and commerce; settling boundary disputes; establishing tax and political regions; detailed city maps for travelers; tracking the weather, and so on.

Over the centuries, man’s view of

his world changed from a narrow local area “flat-earth” view to an

understanding that the world was round and contained other towns, countries,

and even continents on the surface of a sphere.

The challenge was how to accurately represent areas on a curved surface

on a flat map that would be useful for all the applications mentioned

above.

My online research for this

article uncovered some fabulous examples of historic maps that I’m eager to

share with you and relate the appropriate historical context. I’ll also attempt to explain how mathematics

were used to “project” spherical surface features onto flat maps.

I’m going to concentrate on

historical mapping developments in Europe, the Mediterranean region, and the

Near East, because these peoples were the most aggressive in exploring their

world. There were concurrent mapping developments

in Arabia, Persia, China, and India, that I won’t be discussing.

I will talk about the earliest

known maps, maps from the Ancient World, the Middle Ages, the Age of

Exploration, the Industrial Age, the Information Age, and the future of mapping.

Earliest Known Maps

The earliest known maps

are of the stars, not the Earth. Dots

dating to 14,500 BC found on the walls of the Lascaux caves in

southwestern France map out part of the night sky, including well known

individual stars and constellations. The Cuevas de El Castillo in

Spain contain a dot map of the Corona Borealis constellation dating

from 12,000 BC.

Cave painting and rock

carvings used simple visual elements that may have aided in recognizing

landscape features, such as hills or dwellings. Archaeologists believe

that these paintings were used both to navigate the areas they showed and to

portray the areas that people visited.

Maps in the Ancient World

Between 1000 BC - AD 500, ancient

civilizations in the Near East, Greece, and the Roman Empire made increasingly

detailed maps to reflect their expanding knowledge of their surroundings, and

began to incorporate innovations to make maps more useful and accurate.

Near East. Maps were created in ancient Babylonia on

clay tablets. A surviving engraved

tablet map, c. 1400 BC, shows walls and buildings in the holy city of

Nippur. The Babylonian World Map, the

oldest surviving map of the world, c. 600 BC, is a symbolic representation of

the Earth, showing a circular shape surrounded by water, which fits the religious

image of the world in which the Babylonians believed.

|

| Engraved clay tablet of the Babylonian holy city of Nippur, showing walls and buildings, c. 1400 BC. |

Ancient Egyptian maps show an emphasis on geometry and well-developed surveying techniques, perhaps stimulated by the need to re-establish exact boundaries of properties after the annual Nile floods. The Turing Papyrus Map, dated c. 1150 BC, shows the mountains east of the Nile, where gold and silver were mined, along with the location of miners’ shelters, wells, and the road network that linked the elements of the region. The map contains informative inscriptions, has a precise orientation, and is in color.

|

| Fragments of the Turing Papyrus Map, depicting an important mining area, c. 1150 BC. |

Ancient Phoenician sailors made major advances in seafaring and exploration. The first circumnavigation of Africa was accomplished by Phoenicians, c. 600 BC. Unfortunately, nothing certain about their knowledge of geography and navigation has survived. Some historians theorize that the Phoenician circumnavigation of Africa inspired the theory of a spherical Earth.

Greece. Ancient Greeks created the earliest papyrus

maps that were used for navigation and to depict certain areas of the Earth. Early geography and early conceptions of the

Earth lead back to the Greek epic poet Homer.

The depiction of the Earth conceived by Homer, which was accepted by the

early Greeks, represents a circular flat disk surrounded by ocean.

Anaximander was the first ancient

Greek to draw a map of the known world, c. 550 BC, and is considered by many to

be the first mapmaker.

Hecataeus of Meletus produced

another map fifty years later that he claimed was an improvement. Hecatæus's map

describes the earth as a circular plate with an encircling Ocean, and Greece in

the center of the world. This was a very

popular contemporary Greek worldview, derived originally from the Homeric

poems. Also, similar to many other early maps in antiquity, his map has no

scale. As units of measurements, this

map used "days of sailing" on the sea and "days of

marching" on dry land. The work follows the assumption of the author that

the world was divided into two continents, Asia and Europe.

|

| Recreated Hecataeus world map showing Greece at the center of the known world, c. 500 BC. |

While various previous Greek

philosophers presumed the Earth to be spherical, Aristotle (384-322 BC) is

credited with “proving” it, with the following arguments:

·

The lunar eclipse is always circular.

·

Ships seem to sink as they move away from view

and pass over the horizon.

·

Some stars can be seen only from certain parts

of the Earth.

In 240 BC, Eratosthenes, an

astronomer, mathematician, and geographer, was the first to come up with a

scientific estimate of the size of the spherical Earth. He noted the angles of shadows in two cities,

Aswan and Alexandria, which he believed were on the same meridian, at mid-day of

the Summer Solstice, and by performing calculations using his knowledge of

geometry and distance between the cities, was able to make a remarkably

accurate (within 0.5 percent) of the circumference of the Earth (24,860 miles).

Eratosthenes drew a world map,

incorporating information from the campaigns of Alexander the Great and his

successors. Asia became wider,

reflecting the new understanding of the actual size of the continent. Eratosthenes was the first geographer to

incorporate parallels and meridians on his maps, attesting to his understanding

of the spherical nature of the Earth. He

was also the first person to use the word “geography.”

|

| Recreation of Eratosthenes world map, incorporating information from the campaigns of Alexander the Great and his successors, 220 BC. |

Roman Empire. The Roman Empire lasted over 500 years,

from 27 BC to AD 476, and greatly expanded man’s knowledge of the world. During Roman

times, cartographers focused on practical uses: military and administrative

needs. Their need to control the Empire in financial, economic, political, and

military aspects, made evident the need to have maps of administrative

boundaries, physical features, or road networks.

The first great attempt to make

mapping more realistic came in the second century AD with Claudius Ptolemy, Roman

citizen, an astrologer, astronomer, mathematician, and geographer, living in

Alexandria, Egypt. Driven by a desire to

make accurate horoscopes, which required precisely placing someone’s birth town

on a world map, Ptolemy gathered documents detailing the location of towns, and

he augmented that information with the tales of travelers. By the time he was done, he had devised a

system of lines of latitude (parallels) and longitude (meridians), on which he precisely

plotted some 10,000 locations - from Britain to Europe, Asia, and North Africa

- encompassing the known world at that time.

Latitude was measured vertically from the

equator, while longitude was measured from the westernmost landmass known to date,

the Canary Islands off the coast of Spain.

Ptolemy revolutionized the

depiction of the spherical Earth on a flat map by using the mathematics of

perspective projection and Euclidean geometry, where meridians are drawn as

straight lines converging at an imaginary point beyond the north pole, with the

parallels drawn as curved arcs of different length, centered on the same point,

and with fixed positions (latitude and longitude coordinates) of geographic

features. Because the meridian lines are

converging, the map is distorted at the higher latitudes. Ptolemy also informed mapmakers on the size

of the Earth.

Ptolemy’s eight-volume atlas, Geographia,

was a prototype of modern mapping and geographic information systems. It included an index of place names, with the

latitude and longitude of each place, and established the practice of orienting

maps so that north is at the top and east to the right - an almost universal

custom today.

|

| Ptolemy world map, showing the known world at the peak of the Roman Empire. Note the curved lines of latitude and the straight longitude lines, AD 150 (this copy made in 1482). |

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages in Europe lasted

from the late 5th century to the late 15th century, until

merging into the Renaissance and Age of Exploration. After the Roman Empire fell in 476, Ptolemy’s

realistic geography was lost to the West for almost a thousand years.

Medieval maps of the world in Europe were mainly symbolic. These

maps were circular or symmetrical cosmological diagrams representing the Earth’s

single land mass as disk-shaped and surrounded by ocean.

Other maps were concerned with storytelling, including Christian

maps that related stories like Adam and Eve getting tossed out of the Garden of

Eden, and a guide to get one to heaven.

In the early 8th century, Islamic Moors from North Africa,

invaded the Iberian Peninsula (today’s Spain and Portugal) until driven out by

the Spaniards in the late 15th century. The Moors brought with them a

renaissance in art, science and literature, in which for several centuries,

while the rest of Europe was in a state of virtual intellectual stagnation, the

Arabs led the western world.

During

this time, Muslim scholars started to improve maps by using the knowledge,

notes, and writings of the explorers and merchants during their travels across

the Muslim world. There were advances in a more accurate definition of the

measurement units, plus great efforts in trying to describe and define the

calculations of the circumference of the earth. There were also numerous

studies of methodologies to draw a system of meridians and parallels that

helped greatly in the evolution of the science of Cartography.

In

1154, the Arab geographer, Muhammad al Idrisi, working on the island of Sicily,

produced a milestone world map. Tabula

Rogeriana wasn’t just a map of the world - it was an extensively researched

geographical text that covered natural features, ethnic and cultural groups,

socioeconomic features, and other characteristics of every area he mapped. The mapmaking and atlas effort took 18 years,

including the commentaries and illustrations on the maps.

The

atlas was created for King Roger II of Sicily. Al Idrisi drew upon his own extensive travels,

interviews with explorers, and draftsmen paid to travel and map their routes - in

Africa, the Indian Ocean, and the Far East in order to create the maps in the

Tabula Rogeriana. These maps describe the world as a sphere, with a

circumference of 22,900 miles, but divided into seventy different rectangular

sections, each of which was discussed in exacting detail.

The world map, written in Arabic, shows,

the Eurasian continent in its entirety, but only shows

the northern part of the African continent. Notable

features include the correct dual sources of the Nile, the coast of Ghana, and

mentions of Norway. The world map was

produced with north at the bottom, so the map appears “upside down” compared to

modern cartographic conventions.

There is nothing inevitable or intrinsically correct about

the north being represented as up. Some of the very earliest Egyptian

maps show the south as up. And there was

a long stretch in the medieval era when most European maps were drawn with the

east on the top. Arab map makers

often drew maps with the south facing up. For reasons that have been lost to history,

Ptolemy put the north up. Most

cartographers, who made the first big, beautiful maps of the entire world, were

obsessed with Ptolemy and followed his lead.

Al-Idrisi’s Tabula Rogeriana map was the most accurate map of

the world at the time, and remained the most accurate world map for the next

three centuries.

|

| Al-Idrisi's world map, shown upside down here for easier comparison to other maps in this article, c. 1154. |

From 1271 to 1275, Italian Marco

Polo traveled to China and the court of Kublai Khan via central Asia. He

eventually returned home between 1292 and 1295 via Sumatra, India, and

Persia. His account of his travels

spurred a European desire for far eastern riches and contributed a lot to the

knowledge of world geography.

In the same time frame, other Italians produced nautical charts,

not simply maps, but documents showing accurate navigational directions.

In the early 1300s, the Majorcan

Cartographic School, a predominantly Jewish cooperation

of cartographers, cosmographers and navigational

instrument-makers in the late 13th to the 15th century,

operated on the island of Majorca, off the east coast of Spain. With their multicultural heritage, the

Majorcan Cartographic School developed unique cartographic techniques, most

dealing with the Mediterranean. The

Majorcan school was (co-)responsible for the invention of superior, detailed

nautical model charts, gridded by compass lines.

In 1407, a copy of Ptolemy’s Geographia was translated

from Greek into Latin. The book created

a sensation, as it challenged the very basis of Medieval mapmaking - mapmakers

before this had based the proportions of countries, not on mathematical

calculations, but often on the importance of different places - the more

important a country was, the bigger it appeared on the map. Ptolemy’s introduction of mathematics, and

the idea of accurate measurement, were to change the nature of mapmaking

forever.

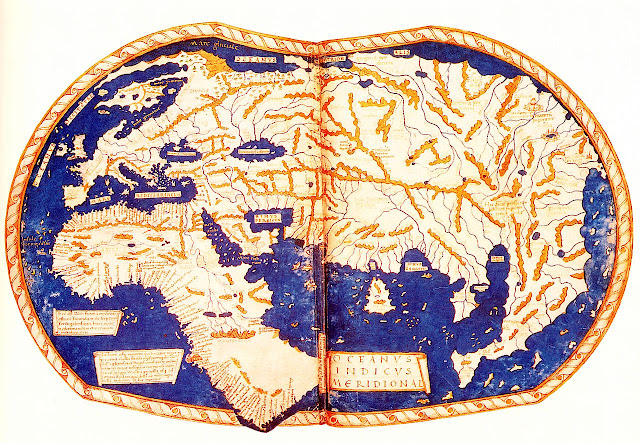

In 1490, German geographer and cartographer, Henricus Martellus

Germanus, working in Florence, Italy at the time, produced a world map showing

heavy influences from Ptolemy, and included the southern passage around Africa

and an enormous new peninsula, southeast Asia.

|

| Henricus Martellus Germanus world map, one of the last maps produced before the discovery of the New World, c. 1490. |

Age of Exploration

The Age of Exploration, also

known as the Age of Discovery, lasted from the beginning of the 15th

century to the mid-17th century - a period of widespread European

exploration of the world, marking the adoption of colonialism as a national

policy in Europe. Extensive lands,

previously unknown to Europeans, were discovered during this period.

There is evidence that Norse

Vikings discovered and attempted to settle North America as early as the late

10th century.

European

exploration outside the Mediterranean started with the Portuguese

discoveries of the

Atlantic archipelagos of Madeira and the Azores in

1419 and 1427 respectively, then the coast of West Africa after 1434,

until the establishment of the sea route to India in 1498

by Vasco da Gama. Portuguese

explorers also discovered the coast of Brazil in 1500, and Australia and the

Spice Islands in 1512. Spain sponsored the transatlantic voyages of

Christopher Columbus to the Americas between 1492 and 1504, the expedition

of Hernan Cortez to Mexico in 1519, the expedition of Francisco Pizzaro to Peru

in 1531, and the first circumnavigation of the globe between 1519 and

1522 by Ferdinand Magellan. France sponsored explorations of the east coast of

America by Giovanni da Verrazano in 1524 and southeastern Canada by Jacques

Cartier in 1534. England sponsored

discovery voyages to eastern Canada by John Cabot in 1497 and Henry Hudson in

1610.

Contrary

to popular opinion, the early European explorers knew that the world was

spherical and not flat. Indeed, on his

first voyage to the Americas, Columbus carried a map influenced by Ptolemy’s

ancient work that described a spherical earth.

But Ptolemy’s estimate of the circumference of the earth was off, and

Columbus thought the world was thirty percent smaller than it actually was, and

anticipated a much shorter voyage to Asia.

These

explorations of discovery led to numerous naval expeditions across the

Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific oceans, and land expeditions in the Americas,

Asia, Africa, and Australia that continued into the late 19th century, followed

by the exploration of the polar regions in the 20th century.

European

overseas exploration led to the rise of global trade and

European colonial empires, with the contact between the Old

World (Europe, Asia and Africa) and the New World (the

Americas), as well as Australia.

European

geographical discoveries allowed the mapping of the entire world,

resulting in a new worldview. As time

went by, and more and more of the world became known, maps began to depict the

new lands. The seacoasts and major

rivers were mapped first, followed by maps of the inland territories.

One

of the first maps to depict the New World was published in 1507 by German

cartographer Martin Waldseemuller. The

map, shown below, uses a modified Ptolemy map projection with curved meridians

to depict the entire surface of the Earth.

Note that only the east coast of the Americas is shown. This was the first time that the name

“America” was used on a map.

|

| World map by Martin Waldseemuller, one of the first to depict the New World, c. 1507. Note that only the eastern coastal areas of the Americas are known at this time. |

The single greatest innovation in mapping after Ptolemy was

produced by Dutch geographer and cartographer Gerardus Mercator in 1569. He invented an improved way to represent the

surface of a globe on a flat map, retaining straight lines of latitude and

longitude, by gradually widening landmasses and oceans the farther north and

south they appear on the map, greatly distorting the size of objects closest to

the poles. The projection preserves the

correct angles between directions within a small area, making it a great aid to

navigation, because lines of constant bearing were straight.

The earliest known terrestrial globe was constructed in the

mid-2nd century BC in Turkey.

The oldest surviving globe was made in 1492 by Martin Behaim, a German

mapmaker, navigator, and merchant. The

globe was constructed of a laminated linen ball reinforced with wood and

overlaid with a map painted by Georg Glockendon. A grapefruit-sized globe, made from two

halves of an ostrich egg, dated from 1504, may be the first globe to show the

New World. Of course, these early globes

could only reflect the knowledge of world geography from that time.

In 1570, Abraham Ortelius, Dutch cartographer, geographer, and

dealer in maps, books, and antiquities, published the first modern atlas, Theatrum

Orbis Terrarum, a collection of 53 uniform map sheets and supporting text

bound to form a book for which copper printing plates were specifically

engraved. The world map from this atlas,

shown below, used Mercator’s projection approach. Note how much more of the world is known at

this date. Note also the hypothetical

continent, Terra Australis (Latin for South Land) that appears on the bottom of

the map. The

existence of Terra Australis was not based on any survey or direct observation,

but rather on the idea that continental land in the Northern Hemisphere should

be balanced by land in the Southern Hemisphere, a theory first expounded in the

5th century.

|

| The Ortelius world map, c. 1570, used Mercator's projection approach. |

Towards the end of the Age of

Exploration, in 1658, Dutch engraver, cartographer, and publisher, Nicolaes

Visscher, produced an engraved double-hemisphere map that included knowledge of

the world to date. Note that California

is depicted as an island, a mistake first made in 1622 that that persisted well

into the 18th century. The

northwestern coastline of North America would not be determined until late in

the 18th century. Note also that the

continent of Antarctica is not shown; the existence of Antarctica would not be proven

until 1820.

|

| Visscher double-hemisphere world map, c. 1658. |

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the nature

of maps began to change from purely information repositories and navigation

aids. Everyday people realized that a

map was an act of persuasion. For

example, maps of towns were used to distinguish land ownership and political

boundaries. Maps were used to settle

arguments. The persuasive power of a map

was its glanceability - data made visual.

Maps conferred power.

With a good map, a military had an advantage in battle. A king knew how much land could be

taxed. Unmapped inland territories cried

out for discovery and colonialism.

Maps were so valuable that seafarers plundered them. Seventeenth century buccaneers exulted in

capturing maps from Spanish ships that showed all the harbors, bays, sand and

rocks, and rising of the land.

Industrial Age

The Industrial Age lasted from the mid-17th century

to the late 20th century - a period characterized in general by inventions

to make manufacturing more efficient. The parallel with mapmaking, the beginning of

modern cartography, was the invention of tools like the compass, telescope, binocular

lenses, the sextant, quadrant, theodolites, and the printing press - permitting

maps to be made more easily and accurately, and printed in large numbers. New technologies also led to the development

of different map projections that more precisely showed the world or focused on

special applications.

There is no

limit to the number of possible map projections. Wikipedia lists over 70 different

projections, including applications for topographic, geological, and thematic

mapping; presentations; navigation; and the United States Geological Survey.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the United

States Geological Survey and the National Geodetic Survey developed tools to

map trails and survey government lands. In

the 20th century, airplanes and satellite aerial photographs changed

the types of data that could be used to create maps.

During this time period there were additional explorations that

added to the knowledge of world geography.

In 1773, Britain’s Captain James Cook discovered islands near Antarctica,

and in 1778 discovered the Hawaiian Islands and explored the coastline of the

Pacific Northwest. The continent of

Antarctica was discovered in 1820.

In 1794, British mathematician and amateur astronomer Samuel Dunn

produced a map of the entire world in a double hemisphere projection. The map followed shortly after the

explorations of Captain Cook in the Arctic and Pacific Northwest. However, when this map was made, few inland

expeditions in America had extended westward beyond the Mississippi River. Antarctica is noticeably absent, 26 years

before its discovery.

|

| World map by Samuel Dunn, 1794. |

In 1851, England’s Sir George Airy established a geographical

meridian reference line that passed through the Royal Observatory at Greenwich

in London, England. According to Airy,

the meridian would represent zero degrees longitude on world maps, and east and

west longitudes would be measured from there around the Earth. By 1884, over two-thirds of all ships used it

as a reference meridian. In October of

that year, the International Meridian Conference adopted Airy’s reference line

as the prime meridian.

|

| The prime meridian was established in 1884. |

Geographical knowledge of the world

continued to progress, particularly in the polar regions and the inland regions

of the world’s continents. Mapmaking

kept pace with increasingly detailed and accurate maps.

In parallel, as the Industrial Age

progressed, trading and commerce increased enormously throughout the world. The era brought the rise of a middle class who

started to be able to afford luxuries such as books and travel. Travel was often necessary for business; now

travel for pleasure expanded rapidly. Geographers

and cartographers responded to the increasing demand for useful maps. Large, decorated, almost artistic

folio maps, so popular during previous centuries, gave way to smaller, more

practical, and portable maps with smaller features that gave more importance to

the accuracy of the elements represented than to the decorative meaning of the

map.

During the 19th century, railroads expanded rapidly

throughout the world, making travel faster, cheaper and more accessible to more

and more people. Cartographers put more of their energy and effort into

producing up-to-date maps, showing the latest extensions to railroad networks. During this time, maps eliminated the

remaining decorative features and became almost entirely factual.

With the introduction of automobiles for general use early in

the 20th century, and the gradual creation of networks of roads and

highways, mapmaking responded again with roadmaps for travelers.

|

| My personal roadmap of Arizona with the roads I've traveled highlighted in yellow. |

Local mapping became deeply granular, especially for

cities. Tourists could confidently tour

new places, their annually updated travel guides in hand, able to located

individual sites and buildings. Being

prominent on local maps was valuable to merchants, so mapmakers sold

“advertising” rights.

Maps could even help win wars.

In the Second World War, Winston Churchill fought with guidance from his

“map room,” an underground chamber where up to 40 military staffers shoved

colored pins into the map-bedecked walls, helping Churchill plan how to defend

the British coast and launch offensive strikes into Germany.

Information Age

The Information Age, also known as the Computer Age or Digital

Age, began in the mid-20th century, characterized by a rapid

transition from traditional industry to information technology associated with

the development of computers and transistors, the fundamental building blocks

of digital electronics.

Modern cartography found an essential tool in the use of

computers, and peripheral instruments like plotters, printers, and scanners,

along with image processing, spatial analysis, and database software. Beginning in 1968, a computerized geographic

information system (GIS) evolved for capturing, storing, checking, manipulating,

and displaying data related to positions on the Earth’s surface. GIS can show many different kinds of data on

one map, such as streets, buildings, and vegetation, enabling people to more

easily see, analyze, and understand patterns and relationships. Globalization of data, with the use of the

internet, web mapping services, and new software applications, plus the

transfer of these tools to mobile devices, has made powerful cartography

available to everyone.

With the exponential increases in technology, the knowledge of

terrestrial Earth has increased. The use

of surveillance aircraft and satellite imagery have documented many areas that

were previously inaccessible. Services

such as Google Earth, and other free online digital maps, have made accurate

maps of the world more accessible than ever before.

|

| Google Earth map of a portion of London, England. |

The convenience of the satellite Global Positioning System and

online mapping means we live in an increasingly cartographic age. Many online searches produce a map as part of

the search results - for a local store, a vacation spot, live traffic updates,

and so on. People today see and interact

with maps every day.

These days, our maps seem alive:

they speak, in robotic voices, telling us precisely where to go - guided

by satellites and mapping of companies like Google, Bing, and Mapquest,

providing turn by turn directions and time to destination. There’s no need to even orient yourself to

north: the voice tells you turn right,

turn left, with you always at the center. And these capabilities are now available in

our automobiles, on our smart phones, and even on our watches.

|

| Map and directions from Mapquest for the San Francisco area. |

All this technology comes together in apps like Rome2Rio that searches any city, town, landmark attraction, or address across the globe to find and display multi-modal routes (trains, buses, ferries, airplanes, cars) to easily get you from point A to B.

Future of Mapping

The future of mapping is tied to

the expanding use of video, lasers, and radar (all together VLR) as a primary

mapping data source and machine learning with artificial intelligence. This means that the mapping pipeline to

ingest data from VLR sensors and mapping software tools we use for mapping

geospatial analytics must change.

Future maps won’t rely on humans

to input fast-paced changes to mapping elements. Instead, they must grow on their own from an

array of VLR sensors deployed across cars, drones, and airplanes. By automatically georegistering (setting

accurate coordinates) all data coming from VLR sensors, a smart map will

confidently update itself to reflect changes such as a terrain shift, status of

construction, location of traffic signs or obstacles, and so on.

A smart map will be aware of its

history and understand important changes taking place in the physical

world. Machine learning software will

generate actionable information. Users

will watch changes play out before their eyes, helping them gain valuable

insights into, for example, how a city, park, building, or road is changing.

Potential applications for future

mapping are mind boggling, and include self-driving cars, urban planning, transportation

planning, defense battle awareness and logistics, first responder directions,

oil and gas physical infrastructure, post disaster damage assessment, fighting

forest fires, electric grid infrastructure status and recovery, weather

prediction and storm warning, crime analysis, pandemic mapping, accident

analysis, environment impact analysis, land use mapping, navigation, natural

resources management, water management, traffic control, pest control,

community development …

Comments

Post a Comment