HISTORY25 - Canada: Part 1

First Peoples to the Dominion of Canada

This Part 1 article is about the

history of Canada, starting from indigenous peoples, then covering first

contact and exploration by Europeans, French rule, and British rule through the

creation of the Dominion of Canada in 1867.

Part 2 of Canadian history, covering the period from the creation of the

Dominion of Canada to the present, will be posted in a future blog.

|

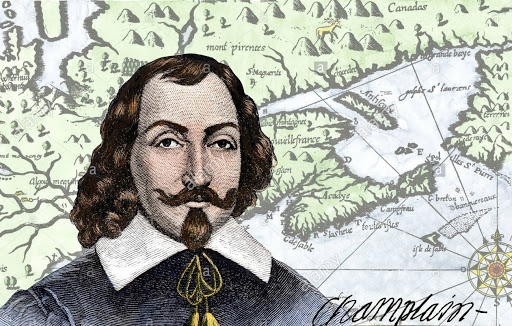

| French explorer Samuel de Champlain and his map of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. |

The article is a follow-on to my recent blogs on the history of Spain and Mexico in North America, and the territorial evolution of the United States.

Natural Landscape

Canada is the second largest

country (counting its waters) in the world after Russia, with a total area of

3,855,100 square miles (about 25% larger than the contiguous United States) and

has the world’s largest proportion (8.92%) of fresh water lakes. Canada’s Arctic islands, Baffin Island,

Victoria Island, and Ellesmere Island are among the ten largest in the world.

Canada has three principle mountainous

regions, including the Coastal Mountains, along the west coast, and the Rocky

Mountains, a few hundred miles inland - both running north-south; and a chain

of mountain ranges extending northwest-southeast across the northern islands.

These mountains are geologically active, particularly in southwestern Canada. The highest mountain in Canada is Mount Logan

at 19,551 feet, in northwestern Canada. The

mountains also contain freshwater glaciers.

The Canadian Shield is a large area of exposed ancient rocks,

covered with a thin layer of soil with lots of forests, that stretches from the

Great Lakes to the Arctic Ocean in eastern and central Canada. The Canadian

Shield is one of the world's richest areas in terms of mineral ores. It is filled with substantial

deposits of nickle, gold, silver, and copper.

Forty two percent of the land

area of Canada is covered by forests, mostly spruce, poplar, and pine.

Average winter and summer high

temperatures across Canada range from Arctic weather in the north, to hot

summers in southern regions, with four distinct seasons. Ice is prominent in the northerly Arctic

regions and through the Rocky Mountains, and the relatively flat Canadian

prairies in the southwest facilitate productive agriculture. The Great Lakes feed the St. Lawrence River

(in the southeast) where the lowlands host much of Canada’s population.

|

| The natural landscape of Canada. |

Indigenous Peoples

North

America’s first humans probably migrated from Asia, over a now-submerged land

bridge from Siberia to Alaska from about 45,000 to 12,000 years ago, during the

last Ice Age. Unknown numbers of people moved southward along the western edge

of the North American ice cap and then eastward at the southern limit of the

ice cap. The presence of the ice, which for a time virtually covered Canada,

makes it reasonable to assume that the southern reaches of North America were

settled before Canada, and that the Inuit (Eskimo) who live in Canada’s Arctic regions today

were the last of the aboriginal peoples to reach Canada.

By

about 11,000 years ago some of the earliest peoples began to move northward

into Canada as the southern edge of the continental glaciers retreated.

Over

thousands of years, as the climate warmed, early North Americans evolved from

hunting large game animals, that eventually died off, to supplementing their

diets with smaller game, fish, and a variety of edible wild plants (hunter

gatherers), to growing their own crops.

The transition from a hunter-gatherer way of life to one centered on

farming, led to permanent small settlements.

They established villages and eventually farming and fishing

communities.

Although

there are no written records detailing the history of Canada’s indigenous

civilizations just before contact with Europeans, archaeological evidence and

oral traditions give a reasonably complete picture. There were 12 major

language groups among the peoples living in what is now Canada: Algonquian, Iroquoian, Siouan, Athabascan, Kootenaian, Salishan,

Wakashan, Tsimshian,

Haidan, Tlingit, Inuktitut, and Beothukan. Within each language group there

were usually political and cultural divisions.

Among

the Iroquoian people, for example, there were two major subgroups, the Iroquois and the Huron. These subgroups were further divided. At the

time of contact with Europeans, the Iroquois had organized themselves into the

Iroquois Confederacy, consisting of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and

Seneca peoples. A sixth group, the

Tuscarora, joined later.

Considerable

variation in cultures, means of subsistence, tribal laws and customs, and

philosophies of trade and intertribal relations existed. In southeastern Canada, the Eastern Woodland Indians, such as the Huron, Iroquois, Petun, Neutral, Ottawa, and Algonquin, created a mixed subsistence economy of

hunting and agriculture supplemented by trade. Semi-permanent villages were

built, trails were cleared between villages, fields were cultivated, and game

was hunted. There was a high level of political organization among some of

these peoples; both the Huron and the Iroquois formed political and religious

confederacies and created extensive trade systems and political alliances with

other groups.

On

the Great Plains, the Cree depended on the vast herds of bison to supply

food and many of their other needs.

To

the northwest were Athabaskan and Tlingit peoples, who lived on the islands of southern Alaska and northern British Columbia.

To

the west, the interior of today's British Columbia was home to the Salishan and southern Athabaskan language groups. The

inlets and valleys of the British Columbia coast sheltered large, distinctive native populations,

sustained by the region's abundant salmon and shellfish. These peoples developed complex cultures dependent

on the western red cedar that included wooden houses, seagoing

whaling and war canoes and elaborately carved totem poles.

Peoples

living in the far north do not appear to have formed larger political

communities, while those of the west coast and the Eastern Woodlands formed

sophisticated political, social, and cultural institutions.

Climate

and geography undoubtedly were major factors affecting the nature of the

societies that evolved in the various regions of Canada. The one characteristic

virtually all the groups in Canada shared, before contact with Europeans, was

that they were self-governing and politically independent.

The location of indigenous peoples during the early years of European contact.

European Contact and

Exploration

Exploration of Canada by

Europeans began with the Vikings in the late 10th century on the country’s East

Coast. Following John Cabot’s arrival on

the East Coast in 1497, over the course of the next three and a half centuries

British and French explorers gradually moved further west. Commercial,

resource-based interests often drove exploration; for example, a westward route

to Asia and later, the fur trade. By the mid-19th century most of the main

geographical features of Canada had been mapped by European explorers.

A short discussion of

selected major explorations of Canada follows; the map below summarizes the

explorers and their routes during this period.

|

| Selected early explorations of Canada. |

Vikings (circa 1000). Vikings, who had settled

Iceland and Greenland, reached the east coast of Canada around the year 1000

and established as many as three small settlements on the northern tip of

Newfoundland. The settlements were soon

abandoned for unknown reasons.

John Cabot (1497). Cabot arrived on the

east coast of Canada in 1497 under

a commission from the English king to search for a short route to Asia

(what became known as the Northwest Passage). In that voyage and in a

voyage the following year, during which Cabot died, he and his sons explored

the coasts of Labrador, Newfoundland, and possibly Nova Scotia and discovered the

waters of the Grand Banks (underwater plateaus) southeast of Newfoundland that were

teeming with fish. Soon Portuguese,

Spanish, and French fishing crews braved the Atlantic crossing to fish in the

waters of the Grand Banks.

Jacques Cartier (1535). Frenchman Jacques

Cartier was the first European to navigate the great entrance to Canada,

the Saint Lawrence River. In 1535, Cartier explored the Gulf of St.

Lawrence and claimed its shores for the French crown. In the following year, Cartier ascended the

river itself and visited the sites of modern Quebec City and Montreal. In 1541, the French king, anxious to challenge

the claims of Spain in the New World, decided to set up a fortified settlement just

north of Quebec City, but it failed.

Henry Hudson (1610-11). In 1609, English sea

explorer Henry Hudson, looking for a northwest passage to Asia, landed at the

site of modern New York city and sailed up the Hudson River. In 1610-11, on a second expedition, still

looking for a northwest passage, Hudson became the first European to see

Canada’s Hudson Strait and the immense Hudson Bay. After wintering on the shore of James Bay,

Hudson wanted to press on to the west, but most of the crew mutinied, casting

Hudson, his son, and seven others adrift, never to be seen again. Several follow-on English explorations to

Hudson Bay allowed the Hudson’s Bay Company (fur trading business) to exploit a

lucrative fur trade along its shores for more than two centuries.

Samuel de Champlain

(1613-15). After

helping to found and settle the French colony of Acadia in today’s eastern Canada’s

mainland and the Maritime provinces (1604-5), in 1608, French navigator Samuel

de Champlain founded what is now Quebec City, one of the earliest

permanent settlements, which would become the capital of New France, French

colonies in North America. He took personal administration over the city and

its affairs, and sent out expeditions to explore the interior. From 1613-15, he explored the upper Saint

Lawrence basin, traveling westward by canoe on rivers to the eastern Great

Lakes and then eastward to the future northeastern United States, securing the

mid-continent for the French fur trade. During

these voyages, Champlain aided the indigenous Hurons in their battles against

the Iroquois Confederacy. As a result,

the Iroquois would become enemies of the French and be involved in multiple

conflicts.

Pierre Gaultier de

Varennes, sieur de La Vérendrye (1731-41).

La Vérendrye was a French military

officer, fur trader and explorer. In the 1730s, he and his four sons explored

the area west of Lake Superior and established trading posts there.

They were part of a process that added Western Canada to the original

New France territory that was centered along the Saint Lawrence basin. He was the first known European

to reach present-day North Dakota and the upper Missouri

River in the United States. In the 1740s, two of his

sons crossed the prairie as far as present-day Wyoming, and were the

first Europeans to see the Rocky Mountains north of New Mexico

James Cook (1778). British explorer James

Cook, a Captain in the British Navy, after making detailed maps of

Newfoundland, being the first to reach the eastern coastline of Australia and

the Hawaiian Islands, and the first to circumnavigate New Zealand, in 1778, explored

the west coast of North America, north of the Spanish settlements in

California, including from today’s Oregon, along Canada’s west coast, all the

way to and through the Bering Strait until he was stopped by ice. In a single visit, Cook charted the

majority of the North American northwest coastline on world maps for the first

time, determined the extent of Alaska, and closed the gaps in Russian (from the

west) and Spanish (from the south) exploratory probes of the northern limits of

the Pacific.

David Thompson

(1785-1811). David

Thompson was a British fur trader, surveyor, and cartographer who spent his

life exploring and mapping southcentral and southwestern Canada, including

mapping the Columbia River from its source to its mouth. Over Thompson’s career, mostly working for

the North West Company (a fur trading business competitive with the Hudson Bay

Company), he mapped 1.9 million square miles; he has been described as the

“greatest practical land geographer that the world has produced.”

Alexander Mackenzie

(1793). Mackenzie

was a Scottish-born English explorer, who, on behalf of the Northwest Company,

after exploring north from Lake Athabasca in central Canada to the Arctic Ocean

1789, in 1793, completed (in more than one trip) the first east-to-west

crossing of North America north of Mexico (preceding the more famous Lewis and

Clark American expedition by 12 years), reaching the Pacific coast at today’s

Bella Coola in British Columbia.

Simon Fraser (1808). Simon Fraser was an English

fur trader and explorer of Scottish ancestry, who charted much of what is now

the Canadian Province of British Columbia. Alexander Mackenzie’s explorations had been

primarily reconnaissance trips; Fraser’s assignment from the North West Company

was to build trading posts and take possession of the country, as well as to

explore travel routes - a mission he pursued from 1805-08. Fraser established the first permanent

European settlements in the area and his exploratory efforts were partly

responsible for Canada’s boundary later being established at the 49th

parallel.

John Franklin (1845-47). Franklin was a British

Royal Navy officer and explorer who investigated possible sea routes to the

North Pole (1818), surveyed the Pacific coast of Canada (1825-27), and made two

missions to chart Canada’s Arctic coastal mainland. In 1845, Franklin set out from England with

two ships, carrying 128 men, to search the Arctic Ocean for the northwest

passage linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Franklin’s vessels were last sighted by

British whalers north of Baffin Island at the entrance to Lancaster Sound. It was later learned that the icebound ships

were abandoned and the entire crew had died while trying to travel overland.

For centuries, European explorers sought a navigable passage

as a possible trade route to Asia. An ice-bound northern route was discovered

in 1850 by the Irish explorer Robert McClure; it was

through a more southerly opening in an area explored by the Scotsman John Rae in 1854 that Norwegian Roald Amundsen made the first complete passage in 1903-06.

Until 2009, Arctic pack ice prevented regular marine shipping throughout most of the year. Recent

Arctic sea ice decline has rendered the waterways more

navigable.

A northwest passage, between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans was finally discovered in 1850.

The Settlement of New France

The French called their North

American territory New France, first claimed in the name of the King of France

in 1535, during the second voyage of Jacques Cartier. “Canada” was France’s first colony, located

along the Saint Lawrence River, within the larger territory of New France.

The

name “Canada” originates from a Saint-Lawrence Iroquoian word Kanata (or canada)

for “settlement,” “village,” or “land.”

Acadia,

part of today’s Nova Scotia, was France’s second colony in North America, established

in 1604.

By

the early 1700s, New France settlers were well established along the

shores of the Saint Lawrence River and the colony of Acadia, with a

population around 16,000. French explorer, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, had explored the Mississippi River by canoe in

1682-3, giving France a claim to the Mississippi River Valley, where fur

trappers and a few settlers set up scattered forts and settlements.

But

other territory was contested. The

English had claimed St. John's, Newfoundland, in 1583 as the first North

American English colony. They

established other settlements in Newfoundland, and soon after (1607) established

the first successful permanent settlement in the future United States at

Jamestown, Virginia, to the south.

From

1670 on, through the Hudson's Bay Company, the English also laid claim to

Hudson Bay and its drainage basin, known as Rupert's Land, establishing new

trading posts and forts, while continuing to operate fishing settlements in

Newfoundland.

Map of North America in 1702, showing forts, towns, and areas occupied by Europeans Ownership of "striped" regions was disputed.

The

conflict between French, Spanish, and English colonists for control of the

American continent resulted in the Queen Anne’s War (1702-1713) that was fought

in Spanish Florida, New England, Newfoundland, and Acadia. The Treaty of Utrecht ended the war in 1713,

where France ceded the territories of Hudson Bay (Rupert’s Land), Nova Scotia,

and Newfoundland to Britain, while retaining Cape Breton Island and other

islands in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence.

New

France enjoyed steady territorial growth during the early 18th century: in Canada, to the north and east from the

Saint Lawrence River; to the south, from Rupert’s Land, and northwest of the

Great Lakes; in America, far to the south in the Midwest, along the Ohio River

to the east, pushing up against the British American colonies; and along both

sides of the Mississippi River. However,

new arrivals stopped coming from France after Queen Anne’s War, resulting in English

and Scottish settlers in Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and the southern (American)

Thirteen Colonies vastly outnumbering the French population approximately

ten to one by the 1750s.

The greatest extent of New France occurred in the 1750s.

The French and Indian

War (1754-1763) brought New France to an end. The war pitted the

colonies of British America against those of New France, each

side supported by military units from the parent country and by Indian allies. At the start of the war, the French colonies

had a population of roughly 60,000 settlers, compared with 2 million in

the British colonies.

The French and

Indian War was part of the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763),

a global conflict that included colonial rivalries

between Britain and France, as well as territorial disputes

between Prussia and Austria.

The conflict was pursued around the

globe, with fighting in India, North America, Europe, and elsewhere, as well as

on the high seas.

In North America, the

war began with a dispute over control of the

confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers, in Pittsburgh,

Pennsylvania. From there, battles would

be fought in New England, Novia Scotia, and along the Saint Lawrence River. Most of the fighting ended in North America

in 1760, with a British victory over New France, although the war in Europe

between France and Britain continued until 1763.

In

the Treaty of Paris (1763), that officially ended the war: France ceded all its remaining territory in North

America to Britain, except for fishing rights off Newfoundland and the two

small islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, where its fishermen could

dry their fish. France had already

secretly transferred its vast Louisiana territory to Spain under

the Treaty of Fontainebleau (1762). Britain returned to France its most important

sugar-producing colony, Guadeloupe, in the Caribbean, which the French

considered more valuable than Canada.

Also, in 1763, the British created the colony of Quebec.

|

| Map of North America in 1783, showing British territorial gains following the French and Indian War. Note also the presence of Russia in Alaska beginning in 1733. |

Canada Under British Rule

King

George III issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763 following Great

Britain's acquisition of French territory in North America. The proclamation organized Great

Britain's new North American empire and tried to stabilize relations

between the British Crown and native peoples through regulation of

trade, settlement, and land purchases on the western frontier.

During

the American Revolution (1775-1783), there was some sympathy for

the American cause among the Acadians and the New Englanders

in Nova Scotia. Neither party joined the

rebels, although several hundred individuals joined the revolutionary cause. An invasion of Quebec by

the Continental Army in 1775, with a goal to take Quebec from British

control, was halted at the Battle of Quebec. The defeat of the British army during

the Siege of Yorktown (with Americans getting considerable help from the

French) in October 1781 signaled the end of Britain's struggle to suppress

the American Revolution.

|

| North America after the American Revolution. Britain lost a sot of territory, but remained a power in North America. |

When

the British evacuated New York City in 1783, they took many Loyalist

refugees to Nova Scotia, while other Loyalists went to southwestern Quebec. So

many Loyalists arrived on the shores of the St. John River that a

separate colony - New Brunswick - was created in 1784.

After

1790 most of the new settlers were American farmers searching for new lands.

In

the Constitutional Act of 1791, the Province of Quebec was divided in two. The largely

unpopulated English-speaking Loyalist western half became Upper

Canada, and the largely

French-speaking eastern half became Lower Canada. The names “Upper” and “Lower”

Canada were given according to their location along the St. Lawrence

River. Upper Canada’s people were mostly

members of the Anglican Church of England and received English law and

institutions, while Lower Canada retained French civil law and institutions,

including feudal land tenure and the privileges accorded to

the Roman Catholic Church.

The War

of 1812 was fought between the United States and the British, prompted by

restrictions on U.S. trade from British blockades and by British and Canadian

support for North American Indians trying to resist westward expansion. Greatly outgunned by the British Royal

Navy, the Americans focused on invasions of Canada, especially north of the

Great Lakes in Upper Canada. The American frontier states supported the war to

suppress the Indian raids that frustrated settlement of the frontier. The war on the British border with the United

States was characterized by a series of multiple failed invasions and fiascos

on both sides. But the American forces did

take control of Lake Erie in 1813, driving the British out of the

region, and breaking the power of the Indian confederacy. The War ended with no boundary changes. A demographic result was the shifting of the

destination of American migration from Upper Canada

to Ohio, Indiana and Michigan, without fear of Indian

attacks.

The Treaty of 1818 between the

United States and the United Kingdom resolved British southcentral boundary

issues. The two nations agreed to a 49th

parallel central boundary line, because a straight-line boundary would be

easier to survey than the pre-existing boundaries based on watersheds. The British ceded all of the so-called Rupert's

Land, south of the 49th parallel, east of the Continental Divide,

covering the northern parts of today’s North Dakota and Minnesota. The United States ceded the northernmost edge

of the Louisiana territory, north of the 49th parallel and north of

today’s state of Montana. The treaty also

allowed for joint occupation and settlement of the Oregon Country to the

west.

In

the late 1700s and early 1800s, Spain’s long-standing claims to the

northwestern U.S and Canadian Pacific coasts began to be challenged in the form

of British and Russian fur trading and colonization. (See European Contact and Exploration above.) In the end, Spain withdrew from the North

Pacific and gave up its claims to the region in the Adams-Onis Treaty of 1819,

leaving the eventual settlement of the future border of British Columbia to

Great Britain and the U.S. (See below.)

The

rest of North America also was experiencing significant changes. In 1801, Spain had ceded Louisiana back to

France in exchange for territories in Tuscany, Italy, and in 1803, France,

desperate for funds to pursue European interests, sold the territory to the

U.S. for $15 million in the Louisiana Purchase - doubling the size of the U.S. In 1810, Mexico began its fight for

independence from Spain, achieving that goal in 1821, taking over all Spanish

territory in North America.

North America in 1837. British North America (in today's Canada) a has expanded to the west and north.

The

Anglo-Russian Convention of 1825 settled the boundary between Russian

and British territorial possessions on the Pacific Coast, including the Russian Alaskan fishing-rights-related

southernmost boundary at the 54-degree, 40-minutes north parallel, the present

southern tip of the Alaska Panhandle, and set the current eastern boundary of

Alaska along the 141st meridian.

From

about 1815 to 1850, some 800,000 immigrants came to the colonies of British

North America, mainly from the British Isles. These included Gaelic-speaking Highland

Scots to Nova Scotia and Scottish and English settlers, particularly to Upper

Canada. The Irish Famine of the 1840s significantly increased the pace

of Irish Catholic immigration to British North America, with over

35,000 distressed Irish landing in Toronto alone in 1847 and 1848.

Dominion

of Canada

In

1837-38, armed uprisings had taken place in Lower and Upper Canada. The rebellions were motivated by frustrations

with political reform. A key shared goal

was responsible government. The

Rebellions of 1837-38 led directly to the Constitution Act of 1867 which

created the country of Canada and its government.

The

Act created a Canadian confederation by uniting the North American British

provinces. The Act created the Dominion

of Canada, and defined a major part of the constitution of the new country, similar

in principle to that of the United Kingdom, including its federal structure,

the House of Commons, the Senate, the justice system, and the taxation

system. The term “dominion” was chosen

to indicate Canada’s status as a self-governing colony of the British Empire. The name of the country was confirmed as “Canada” and the

city of Ottawa was named the capital of the country.

The Dominion of Canada was established initially with three

provinces: Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick. The Province of Canada was

divided into Ontario and Quebec so that each linguistic group would have its

own province. Both Quebec and Ontario

were required to safeguard existing educational rights and privileges of

Protestant and the Catholic minority. Thus, separate Catholic schools

and school boards were permitted in Ontario. Toronto was formally established as Ontario's

provincial capital.

Meanwhile, the Webster-Ashburton

Treaty of 1842, had settled two border disputes between the United Kingdom and

the U.S. Along the U.S. Maine northern border,

the British gained 5,000 square miles of disputed territory, but to the west

along the U.S. Minnesota northern border, the British lost 6,500 square miles

of land.

Also, the Oregon Treaty of 1846,

settled the Pacific Coast (British Columbia) boundary issue between Great

Britain and the U.S. at the 49th parallel north. Vancouver Island was an exception and

retained in its entirety by the British.

British Columbia became an

official North American territory of Great Britain in 1858, and the

North-Western Territory was established in 1859. The Rupert’s Land territory and Newfoundland territory

had been ceded to Great Britain by France in 1713.

Comments

Post a Comment