HISTORY22 - New Spain Expands to the North

This article covers the expansion of the Spanish Empire from Mesoamerica to the north, both during the conquest of Mesoamerica and the following Colonial Period. The time period begins in the 1530s, with exploration of the northern territories, and extends to 1821, when Mexico gained its independence from Spain.

My previous two blog articles cover the Development of ancient Mesoamerican Civilizations and the Spanish Conquest of Mesoamerica.

In 1521, after the fall of the

Aztec capital, Tenochtitlán, to Spanish Conquistador Hernán Cortés, Spain

established the Viceroyalty of New Spain, an integral territorial entity of the

worldwide Spanish Empire, with its capital in Mexico City on the obliterated

site of Tenochtitlán. New Spain

continued to grow to the south, as the Spanish conquered the rest of

Mesoamerica and Central America; and also grew to the north, as Spain turned

its attention to new lands.

By 1531, the Spanish had conquered

the Aztec Empire in Central Mexico and the Tarascan State to the west, and

began looking north in the hope of discovering new wealthy civilizations to

conquer, precious metals to mine, indigenous peoples to convert to

Christianity, and later, to forestall incursions by the British and French.

After the conquest of central Mexico, Spain turned its attention to new lands.

Exploration

The first European to visit

northern Mexico and the southwestern U.S. was Spanish explorer Cabeza de Vaca,

who survived a ship wreck near present day Galveston, Texas in 1528, and for

the next eight years, with a handful of other survivors, explored on foot what

is now Texas, northeastern Mexico, parts of New Mexico and Arizona, then down

the Gulf of California Coast to finally reach Mexico City in 1536.

Also, in 1536, Conquistador

Hernán Cortés explored the northwestern part of Mexico, discovered the Baja

California Peninsula, and explored the Pacific Coast of Mexico.

Based on de Vaca’s description of

riches in the northern lands (the mythical seven cities of gold), Spanish Conquistador

Francisco Vazquez de Coronado, from 1540-1542, led a large expedition from

Mexico, north to present day Kansas, through northern Mexico and parts of the southwestern

U.S. Though Coronado found no gold, his

was the first systematic exploration of the new lands and served as a

springboard for future explorers and colonizers.

Coronado's route on his 1540-1542 exploration of northern Mexico and southwestern U.S.

For reference as we discuss Spanish settlement northward, a map of the current states of Mexico is provided below.

The black line across the map is the approximate division between Mesoamerica (to the south) and the Spanish northern expansion region in Mexico.

Northern Mexico

After conquering the Tarascans in

the Michoacan state of central Mexico in 1531, brutal Spanish Conquistador Nuño

Guzmán proceeded to launch a fierce campaign north into the lands of the

Chichimeca, a nomadic people who invaded central Mexico from the north in the

12th and 13th centuries.

Typically, the conquistadors attacked an Indian village, stole the corn

and other food, razed and burned the dwellings, and tortured the native leaders

to gather information on what riches were in the area. For the most part, these riches did not

exist.

Undeterred, Guzmán continued the

violent suppression of the Chichimecas and in 1531, established the Kingdom of

New Galicia, covering the present-day Mexican states of Aguascalientes,

Guanajuato, Colima, Jalisco, Nayarit, and Zacatecas. San Blas, on Nayarit’s Pacific coast, was

founded in 1530 and would eventually become a jumping off place for military

missions to Sinaloa, Sonora, and California.

The

discovery of silver deposits in Zacatecas and Guanajuato in the mid-1500s, and

later in San Luis Potosí (1592) caused a frenzy of mining activity. (During Colonial times, nearly one-third of

all the silver mined in the world came from the Guanajuato region.)

But, Guzmán’s violent conquest of

New Galicia had left Spanish control unstable.

The Chichimeca War (1550-1590) started with the natives attacking

travelers and merchants along the “silver roads.” This war would become the longest and

costliest conflict between Spanish forces and indigenous peoples in the

Americas. Thousands of Spanish died and

mining settlements in Chichimeca territory were continually under threat. With no military end in sight, in 1590,

Spanish authorities launched an intensive peace offensive by offering the

Chichimecas lands, agricultural supplies, and other goods. This “peace by purchase” finally brought an

end to the war.

Silver

mining stimulated northcentral Mexico’s development to supply the mines with

food and livestock. This was rich,

fertile lowland (called the Bajío) just north of central Mexico. Devoid of settled indigenous populations in

the early sixteenth century, the Bajío did not initially attract Spaniards, who

were much more interested in exploiting labor and collecting tribute whenever

possible. The region did not have indigenous populations that practiced

subsistence agriculture. The Bajío developed in the Colonial Period as a region

of commercial agriculture.

The Bajio developed as a region of commercial agriculture.

Francisco de Ibarra explored and settled much of northwestern Mexico.

Spanish settlement of northeastern Mexico proceeded along the same general timeline as that of Nueva Vizcaya, on lands that would become the Province of Nuevo Santander, the New Kingdom of Leon, and the Province of Nueva Extremadura - the current Mexican states of Tamaulipas, Nuevo Leon, and northeastern Coahuila. The city of Monterrey was founded in 1596, but wouldn’t become a key economic center until after Mexican independence. The city of Ciudad Juarez was founded in 1659 on the Rio Grande River opposite today’s El Paso, Texas.

There

was widespread resistance to Spanish colonization by indigenous peoples

throughout all of northern Mexico, with uprisings and rebellions lasting until

the late 1700s.

Religious missions were an integral part of the northern

frontier of New Spain and were established over a vast area. From the early

seventeenth century to the early nineteenth century, missionaries of the Roman

Catholic Church built missions throughout what is now northern Mexico and the

southwestern United States. The Church,

together with military and secular entities, established European order in the

region. The missionaries were the first to enter these frontier zones in an

attempt to convert native populations to Christianity. The missions also served

as a vanguard for the expansion of Spanish settlements and mining operations.

New

Mexico/Arizona

After

making peace with the indigenous semi-nomadic Chichimeca peoples of northcentral

Mexico in 1590, Spanish attention again turned northward. In 1595, Don Juan de Oñate received official

permission to explore and colonize lands in present-day New Mexico, then very

sparsely populated by indigenous pueblo peoples, mostly in central and northern

New Mexico, along the Rio Grande River.

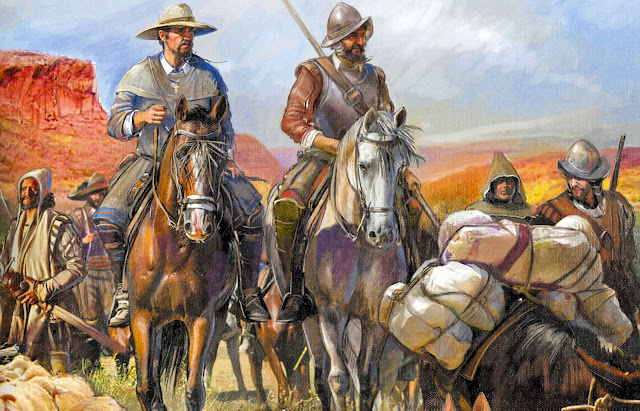

In 1598, Oñate made his first foray from today’s Mexican state of

Chihuahua into the new lands, traveling up the Rio Grande Valley, with a large

group of soldiers, settlers, and missionaries, reaching northern New Mexico to

establish the first European settlement in New Mexico near today’s Santa Fe. In that same year, the Province of Nueva

Mexico was officially created by the Spanish King with Oñate named as its first

Governor.

The

indigenous pueblo people at Acoma revolted against this Spanish

encroachment and faced severe suppression. In battles with the Acomas, Oñate

lost 11 soldiers and two servants, killed hundreds of Indians, and punished

every man over 25 years of age by the amputation of their left foot.

In 1604-1605, Oñate made an extensive exploration of today’s Arizona, marching

west from New Mexico, past the Zuni and Hopi villages in Arizona, reaching the

Verde Valley and the Prescott area, finally arriving at the Colorado River, and

then heading south to the Gulf of California.

Native Indian pueblos and Spanish towns in early Spanish New Mexico.

Oñate’s missionaries began an 80-year period of mission building at over 20 native pueblos across northern New Mexico, plus three missions as far west as the Hopi pueblos in northeastern Arizona. But both the colonists and the missionaries depended on native labor and competed with each other to control a decreasing population (because of high mortality to European diseases). They exploited native labor for transport, sold native slaves in New Spain, and sold goods produced by the slaves. Moreover, the missionaries tried to totally eliminate native religious practices - efforts that included imprisonment, execution, and destroying religious articles.

In 1606, Oñate was recalled to Mexico City and was tried and convicted

of cruelty to both natives and colonists.

He was banished from New Mexico for life and exiled from Mexico City for

five years. He died in Spain in 1626 and

is sometimes called the “last Conquistador.”

|

| Don Juan de Onate, the "last Conquistador," settled much of northwestern Mexico. |

In 1609, the Spanish moved their initial settlement from San Juan to

Santa Fe, about 25 miles to the southeast at the foot of the Sange de Cristo

Mountains, because of the constant threat of non-indigenous, nomadic Native

Americans, principally the Apache. In

1610, the Spaniards made the settlement of Santa Fe capital of the New Mexico

territory.

In 1680, the pueblo people accomplished

a well-coordinated revolt (Pueblo Revolt), killing about 800 Spaniards and

driving an additional 2,000 from northeastern Arizona and all but the southern

portion of New Mexico. Most of the

missions were demolished or burned.

The

small village of El Paso was established in 1680 in West Texas, across the Rio

Grande River from Ciudad Juarez, as a temporary base for the Spanish governance

of the territory of New Mexico as a result of the Pueblo Revolt.

It took until 1692 for the Spanish

to reestablish control in New Mexico.

Spanish settlers had first arrived

at the site of Albuquerque in the mid-17th century and established

several Haciendas and farms. After the

Pueblo Revolt, settlers returned to Albuquerque and in 1706 the Spanish colonial town of Albuquerque

was founded.

Meanwhile, to the southwest, in 1687,

missionary Eusebio Kino arrived in today’s Mexican state of Sonora and began to

establish missions in northern Sonora, and by 1691, in today’s southeastern

Arizona. Before his death in 1711, Kino

would establish over 20 missions, including several along the Santa Cruz River

in Arizona, among the generally peaceful indigenous Pima and Tohono O’odham

peoples.

Missions and towns in early Spanish Sonora and Arizona.

Spanish settlement of southeastern

Arizona began in the late 1690s, with a small cattle ranch near today’s

Mexico-U.S. border at the headwaters of the Santa Cruz River. Additional settlers followed, attracted by

the fertile Santa Cruz Valley and silver mining interests.

While Father Kino was establishing his

missions, non-indigenous nomadic Apaches began raiding from Arizona and New

Mexico into Sonora and Chihuahua. As the

Apache continually attacked settlements, ranches, and mining camps - gradually

assimilating local native groups - the Spanish were forced to build a series of

presidios (forts) to contain the threat.

In 1752, the Spanish built a presidio at

Tubac in southern Arizona to protect Spanish interests in the Santa Cruz River

Valley. In 1775 the Spanish moved the

garrison to the new site of Tucson.

During this period of presidio building and relocation, Juan Bautista

de Anza, Spanish Captain of the Tubac Presidio, and later to be the Governor of

New Mexico, made two trips to northern California that established a land route

to the Pacific Coast, brought settlers to California’s Monterey presidio, and explored

San Francisco Bay for future settlement.

The Sonora and Arizona presidios were

largely ineffective in controlling the Apache, so in the late 1780s, the

Spanish changed their approach and offered peace and rations to Apaches who

settled at the presidios (similar to Spanish tactics with the Chichimecas two

hundred years earlier). By 1790, most of

the Apache bands were at peace - that lasted until the 1830s.

To encourage settlement, the Spanish

Colonial Government began issuing land grants in southeastern Arizona. For the last 30 years of New Spain’s control,

most of the growth in southeastern Arizona occurred in the Santa Cruz Valley.

In 1732, the new Province of Nueva

Navarra had been formed and added to New Spain to include lands to the west and

north of the Province of Nueva Vizcaya.

The new province included the western parts of the present-day Mexican

states of Sinaloa and Sonora, and present-day southern Arizona, as far north as

the Gila River.

California

Spanish

exploration of the Pacific Coast of California began in 1542 when Juan Cabrillo

landed at today’s San Diego Bay and then sailed up the coast. Cabrillo’s voyage was largely unnoticed by

Spanish authorities and it wasn’t until 1602 that Sebastián Vizcaino sailed up

the Pacific Coast as far as present-day Oregon, and named California coastal

features from San Diego to as far north as the Bay of Monterey.

Not

until the eighteenth century was California of much interest to the Spanish

crown, since California had no known rich mineral deposits or indigenous

populations sufficiently organized to render tribute and perform labor for

Spaniards. (The discovery of huge deposits of gold in the Sierra Nevada foothills did not

come until after the U.S. had incorporated California following the Mexican-American War [1846–48]).

By

the early 1800s, Spanish missionaries had established over 20 missions on

the lower California peninsula.

Spanish missions on the lower California peninsula.

In

1768, Spain decided to "Occupy and fortify San Diego and Monterey for God

and the King of Spain." The Spanish colonization there, with far fewer known

natural resources and less cultural development than Mexico, was to combine

establishing a presence for defense of the territory with a perceived

responsibility to convert the indigenous people to Christianity.

Between

1769 and 1804, in upper California, the Spanish established 19 missions and five

presidios to protect the missionaries and settlers. The first upper California mission and

presidio were established by Friar Junipero Serra and Gaspar de Portola in San

Diego in 1769. In 1771, Father Serra

directed the building of Mission San Gabriel and ten years later, in 1781,

settlers founded the Los Angeles pueblo there.

Presidios

were also established at Monterey, San Francisco, Santa Barbara, and Sonoma.

Spanish missions in upper California.

In

1804, the crown created two new provinces of New Spain. The southern peninsula became Baja

California, or Vieja (old) California, and the ill-defined northern mainland

frontier area became Alta (upper) California, or Nueva California. Baja California eventually became the

present-day Mexican states of Baja California and Baja California Sur. The vast Alta California claimed territory

included all the modern U.S. states of California, Nevada, Utah, and parts of

Arizona, Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico.

Once

missions and protective presidios were established in an area, large land grants encouraged settlement and establishment

of California ranchos. The Spanish system of land grants was not

very successful, however, because the grants were merely royal concessions - not

actual land ownership. Under later Mexican rule, land grants conveyed

ownership, and were more successful at promoting settlement.

Rancho

activities centered on cattle-raising; many grantees emulated the Dons of Spain, with cattle, horses and sheep as the sources

of wealth. The work was usually done by Native Americans, sometimes displaced and/or relocated from

their villages. Native-born descendants

of the resident Spanish-heritage rancho grantees, soldiers, servants,

merchants, craftsmen and others became the Californios.

Many of the less-affluent men took native wives, and many daughters married

later English, French and American settlers.

Spain

never colonized areas beyond the southern and central coastal areas of present-day

California.

Florida

Spanish

Florida was established in 1513 when Juan Ponce de León claimed peninsular

Florida for Spain. Subsequent explorers

landed near Tampa Bay and traveled as far north as the Appalachian Mountains

and as far west as today’s Texas in largely unsuccessful searches for gold.

The

presidio of St. Augustine was founded on Florida’s Atlantic Coast in 1565 and

served as the capital of Spanish Florida for almost 200 years. St. Augustine is the oldest continuously

occupied settlement of European origin in the contiguous United States.

In

the next 22 years, the Spanish established a number of missions and presidios on

the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts of peninsular Florida, up the Atlantic Coast in

today’s Georgia and South Carolina, and inland in South Carolina.

The first Spanish missions and presidios in Florida, 1565-1587.

During the 1600s, a series of missions were established across the Florida panhandle. Pensacola was founded on the western Florida panhandle in 1698. These developments strengthened Spanish claims to the territory.

While

its boundaries were never clearly or formally defined, Spanish Florida extended

over all of present-day Florida, plus portions of Georgia, Alabama,

Mississippi, South Carolina, North Carolina, and southeastern Louisiana.

Spanish

control of Florida was much facilitated by the collapse of native cultures,

mostly caused by a drastic decline in population from European diseases.

The

extent of Spanish Florida started to decline when France established a colony

in New Orleans (1718) and Great Britain established the colonies of Carolina

(1639) and Georgia (1732), over Spanish objections.

Great

Britain had established settlements at Jamestown in 1607 and at Plymouth in

1622, and from there expanded along the American Atlantic Coast to 13 colonies,

stretching from today’s Maine to Georgia, by 1775 at the start of the American

Revolution (1775-1783).

France

started exploring in North America along the St. Lawrence River in the early

1600s, explored to the south and claimed land in today’s American mid-west,

easing up against England’s colonies, building many trading posts, and by the

early 1700s, had expanded southward and begun to settle in today’s southern

Louisiana.

Great

Britain temporarily gained control of Florida in 1763 as a result of the

Anglo-Spanish War, but Florida was returned to the Spanish in 1783 as a

condition of the settlement of the American Revolutionary War.

After a brief diplomatic dispute with the fledgling United States, in 1795, the countries set the northern boundary of Florida (that still extended to the Spanish colony of Louisiana) and allowed Americans free navigation of the Mississippi River.

In the

early 1800s, Florida became an economic burden to Spain, which could not afford

to send settlers or garrisons, so in 1819, the Spanish government decided to

cede the territory to the U.S. in exchange for settling a boundary dispute in

Texas.

Texas

Alonso

Álvarez de Pineda claimed Texas for Spain in 1519, but the area was largely

ignored by Spain until the late 17th century.

In

East Texas, in 1690, Spanish authorities, concerned that France posed a

competitive threat in nearby Louisiana, constructed several missions. Facing steady Native American resistance, the

missionaries returned to Mexico, but in 1716, seeing France settling Louisiana,

mostly in the southern part of the state, Spain responded by establishing new

missions in East Texas. Two years later,

in 1718, they established San Antonio as the first Spanish civilian settlement

in the area.

Hostile

natives and the distance to other Spanish colonies discouraged Spanish settlers

from moving to the area. It was one of

Spain’s least populated provinces.

Native resistance in East and Central Texas, particularly from the

Apache, continued into the late 1700s, but with more missions being

established, by the end of 18th century, only a few nomadic tribes

had not been converted to Christianity.

Missions and presidios built in Spanish Texas, 1659-1795.

Meanwhile,

in West Texas, Native American Comanches were causing trouble. The Comanches were the dominant Native

American group in the Southwest from the 1750s to the 1830s. The huge domain

they ruled was an empire known as Comanchería, extending across today’s

U.S. states of northcentral Texas, eastern New Mexico, Oklahoma, Nebraska, and

southern Kansas. For many years, they

kept the Spanish, and later the Americans, out of their empire.

The

Comanches operated as an autonomous power inside the area claimed by Spain but

not controlled by it. The Comanches used

their military power to obtain supplies and labor from the Spanish, and other Native

Americans through thievery, tribute, and kidnappings, and the Spanish could do

little to stop them because the Comanches controlled most of the horses in the

region and thus had more wealth and mobility.

The

Comanches often raided into northeastern Mexico, in today’s Mexican state of

Coahuila and in response, the Spanish built presidios along the southwestern

Texas frontier.

Native American Comanches operated unchecked within their Comancheria stronghold and raided into bordering country.

In

1819, the boundary between New Spain and the United States, i.e., the boundary

between Spanish Texas and American Louisiana (territory of U.S. since the 1803

Louisiana Purchase) was set at the current border between the U.S. states of

Texas and Louisiana, at the Sabine River.

Eager for new land, many settlers from the U.S., refused to recognize

the agreement and crossed into Spanish Texas to make a new life there.

Spanish

Louisiana

Spanish

Louisiana was a territory of New Spain from 1762-1801 that consisted of vast lands

in the center of North America, encompassing the western basin of the

Mississippi River plus the city of New Orleans.

The area had originally been claimed and controlled by France, but Spain

secretly acquired it from France near the end of the Seven Years War in Europe,

by the Treaty of Fontainebleau (1762).

The new territory also included the trading post of Saint Louis.

New

Orleans was the main port of entry for Spanish supplies sent to American forces

during the Revolutionary War, although Spain and the U.S. disputed navigation

rights on the Mississippi River for the duration of Spain’s rule in Louisiana.

The acquisition of Louisiana consolidated the Spanish Empire

in North America at its greatest extent. When Great Britain returned

Florida to Spain in 1783, after the American Revolutionary War, Spanish

territory completely encircled the Gulf of Mexico and stretched from Florida,

west to the Pacific Ocean, and north to Canada west of the Mississippi River -

a condition that lasted for 18 years.

The greatest extent of the Spanish Empire in North America, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, occurred from 1783-1801, with the acquisition of the Louisiana territory.

Spain

ceded Louisiana back to France in 1801 in exchange for territories in Tuscany, Italy,

and in 1803, France, desperate for funds to pursue European interests, sold the

territory to the U.S. for $15 million (Louisiana Purchase) - doubling the size

of the U.S. at a price of less than three cents per acre.

Adams-Onís Treaty

The Adam-Onís Treaty was an

agreement between the United States and Spain in 1819, signed in 1821, that

ceded Florida to the U.S. and defined the boundary between the U.S. and New

Spain.

The Viceroyalty of New Spain, just before Mexican independence, included northern Mexico and a large portion of the future southwestern United States.

Central America also achieved its

independence in 1821, leaving only Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines as

part of New Spain.

At the end of the Spanish

American War in 1898, these last remaining parts of New Spain came under the

control of the United States.

Comments

Post a Comment