HISTORY21 - Spanish Conquest of Mesoamerica

This article is the about the

history of the Spanish Conquest of Mesoamerica, lands on the isthmus joining

North and South America, between 10-22 degrees north latitude, through the

Spanish Conquest period from 1519 to 1697.

This blog is a follow-on to my

last posted blog, the History of Ancient Mesoamerica, which presented

the history of six advanced Mesoamerican civilizations, including the Aztec and

Maya, whose conquest by the Spanish is described below.

The Spanish established the first

permanent settlement in the New World on the island of Hispaniola (in the

Greater Antilles) in 1493 on the second voyage of Christopher Columbus. Over the next 25 years, there were further

explorations and settlements on islands in the Caribbean Sea and explorations

along the North and South American mainland, including a number of visits to

the coast of the Yucatán peninsula. The

Spanish were seeking wealth in the form of gold and access to indigenous labor

to mine gold and to perform other manual tasks.

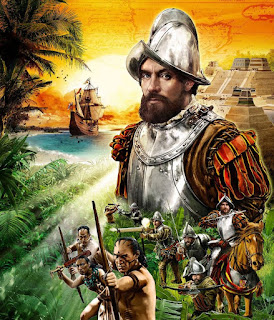

Fresh from explorations of the

Yucatán coast, in April 1519, Spanish Conquistador Hernán Cortés landed on the

coast of the modern-day Mexican state of Veracruz, determined to conquer the

indigenous Aztecs and reap the spoils of their magnificent capital of

Tenochtitlán. The Aztec civilization was

at the peak of its power, with an empire extending over central Mexico and

south to the Pacific coast of Guatemala.

The map below shows the extent of

the Aztec Empire.

To the northwest from the Aztecs

were the Michoacan people and the Chichimecas.

Immediately to the east of the Aztec Empire, were the Chiappan peoples

and the indigenous Maya civilization that had survived and prospered for more

than 2,500 years, occupying eastern Mexico, the Yucatán peninsula, Guatemala,

Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador - a territory that covered a third of

Mesoamerica.

Elements of the Spanish

Conquest of Mesoamerica

Before getting started on the

timeline of the Spanish Conquest, I want to address some critical issues that

greatly affected the Conquest and subsequent Colonial Period.

Weapons

and Tactics.

Spanish. Weaponry and tactics for the Spanish differed

greatly from that of the indigenous peoples. This included the Spanish use

of steel swords, crossbows, firearms (including muskets

and cannon), lances, pikes, rapiers, halberds (two-handed pole

weapons), war dogs, and war horses. Horses had never been encountered by

Mesoamericans before, and their use gave the mounted conquistador an

overwhelming advantage over his unmounted opponent, allowing the rider to

strike with greater force while simultaneously making him less vulnerable to

attack. The mounted conquistador was highly maneuverable and this allowed

groups of combatants to quickly disperse themselves across the battlefield. The

horse itself was not passive, and could buffet the enemy combatant.

The

use of steel swords (one- and two-handed broadswords) was perhaps the greatest

technological advantage held by the Spanish.

The

conquistadors applied a more effective military organization and strategic

awareness than their opponents, allowing them to deploy troops and supplies in

a way that increased the Spanish advantage.

The

Spanish routinely employed indigenous allies, either opponents of whomever they

were trying to conquer, or captives from previous conquests. It is estimated that for every Spaniard on

the field of battle, there were at least 10 native auxiliaries, and the

participation of these Mesoamerican allies was decisive.

Spanish Conquistadors received

their charters, defining the scope of particular conquest missions, along with

any restrictions, from the King of Spain, local Governors in the Caribbean, or

later, from authorities in Mexico City.

Individual Conquistadors were very competitive, looking to gain riches

and power. They sometimes ignored their

“orders” and defined their own missions, often having to justify them to authorities

after the fact. In some cases, Spanish

Conquest forces actually fought each other to settle differences in objectives.

Indigenous

Civilizations. The indigenous people of Mesoamerica lacked

key elements of Old World technology, such as the use of iron and steel, and

functional wheels.

Mesoamerican

“armies” were highly disciplined, and warriors participated in regular training

exercises and drills; every able-bodied adult male was available for military

service. Most warriors were not full-time, however, and were primarily farmers;

the needs of their crops usually came before warfare.

Mesoamerican

warfare was not so much aimed at destruction of the enemy as the seizure

of captives and plunder. Indigenous

warriors battled against the Spanish with flint-tipped spears, bows and arrows,

and stones. They also employed two-handed swords crafted from strong wood, with

the blade fashioned from inset obsidian.

They wore padded cotton armor (that had been soaked in salt water

to toughen it) to protect themselves.

(The Spanish were sufficiently impressed by the quilted cotton armor of

their opponents that they eventually adopted it in preference to their own

steel armor.) Warriors bore wooden or

animal hide shields decorated with feathers and animal skins. Some highland Mesoamerican peoples had

historically employed ambush and raiding as their preferred tactic, and its

employment against the Spanish proved troublesome for the Europeans. In response to the use of cavalry, the

highland peoples sometimes took to digging pits on the roads, lining them with

fire-hardened stakes, and camouflaging them with grass and weeds, a tactic that

killed many horses.

European

Diseases. Epidemics accidentally introduced by the

Spanish included smallpox, measles, and influenza. These diseases, together

with typhus and yellow fever, had a major impact on indigenous

populations that had no resistance to them, and were a deciding factor in the

conquest. The Old World diseases decimated populations before battles were even

fought. It is estimated that 90% of the

indigenous population of Mesoamerica had been eliminated by disease within the

first century of European contact.

Religion. During

the conquest, the Spanish pursued a dual policy of military conquest, bringing indigenous

peoples and territory under Spanish control, and spiritual conquest, that is,

conversion of indigenous peoples to Christianity.

The first Franciscan

missionaries to Mesoamerica, sent by the King of Spain at Hernán Cortés

request, arrived in Mexico in 1523 and 1524. By 1559 there were 300 Franciscan friars at 80

missions throughout the conquered areas. The Franciscans concentrated on the densest

and most central communities and built churches, often on the same sacred

ground as Mesoamerican temples. They

targeted native elites as key converts, who would set the precedent for the

commoners in communities to convert.

Since it was customary

for Mesoamerican cultures to adopt the religion of conquering tribes, the

natives were not naturally inclined to resist conversion to Christianity.

Although their chief

goal was to perform the sacraments and introduce the natives to the

fundamentals of Roman Catholic doctrine, in many respects the missionary friars

laid the groundwork for the fusion of the Spanish and Mexican cultures. They

won the trust of the native population by protecting them from the excesses to

which many of the Spanish civilians were inclined. They also took

responsibility for the basic education of the natives, an effort greatly

enhanced by their assiduous study of native languages. They established schools

where youngsters learned to read and write and were introduced to European

music and the arts. Adults were trained

to practice agriculture and trades, learning European methods in masonry,

carpentry, iron work, weaving, dying, and ceramics.

Timeline of the Spanish

Conquest of Mesoamerica

Now let’s talk about the timeline

of the Spanish Conquest period, starting from 1519 with the Aztec Empire, then

extending to the Michoacan people, the Chichimecas, the Chiappan peoples, and

the Maya civilization - in the order of completing the conquest of the region. I’ll spend a lot more time and detail on the

conquest of the Aztecs, compared to the other civilizations, because of its

overall importance to the conquest of Mesoamerica.

Central Mexico (1519-1524): Aztec Empire.

By the early 16th century, the Aztecs had come to dominate

central Mexico, and ruled up to 500 small states, and some five to six million

people, either by conquest or commerce.

The Aztec Empire extended from central Mexico, far south to today’s

Mexican state of Chiapas and Guatemala, and spanning from the Pacific to the

Atlantic Oceans.

The Aztec capital, Tenochtitlán,

was founded on an islet in Lake Texcoco, the inland lake system of the Valley

of Mexico, grew to cover about five square miles, with an estimated 200,000

inhabitants. The city was connected to

the mainland by bridges and causeways, and interlaced with a series of canals,

so that all sections of the city could be visited either on foot or via

canoe. Two aqueducts, each more than two

and a half miles long, provided the city with fresh water from springs on the

mainland.

In the center of the city were

hundreds of buildings, including public buildings, temples, and palaces. Inside a walled square, 1,640 feet on a side,

was the ceremonial center, including the 200-feet high Templo Mayor pyramid,

dedicated to the Aztec patron deity (god of war, sun, and human sacrifice),

Huitzilopochtli, and the Rain God, Tlaloc; the temple of Quetzalcoatl, a

ball-game court; the Sun Temple; a building dedicated to warriors and the

ancient power of rulers; platforms for gladiatorial sacrifice; and other minor

temples.

On April 21, 1519, at the height

of the Aztec civilization, Spanish conquistadors, led by Hernán Cortés, landed

an expeditionary force of about 600 men on today’s Gulf Coast site of Veracruz,

about 200 miles from Tenochtitlán.

Cortés was welcomed by representatives of the Aztec Emperor, Moctezuma

II, bearing lavish gifts of gold and cloth and who attempted to dissuade Cortés

from visiting Tenochtitlán. But the

lavish gifts and polite welcoming only encouraged Cortés on his quest towards

the Aztec capital.

Over the next few months, Cortés

persuaded local indigenous settlements to rebel against the Aztecs. His new allies helped Cortés establish a

Spanish settlement at Villa Rica, a few miles north of Veracruz along the Gulf

Coast, that would become his starting point for his attempt to conquer the

Aztec Empire.

In mid-August, the Spaniards and

their new allies started the march towards Tenochtitlán. In early September, Cortés arrived at

Tlaxcala, a confederacy of about 200 towns and different tribes, who were

hold-out enemies of Tenochtitlán. After

a series of battles, Cortés persuaded the Tlaxcalans to join his forces to

fight against their enemies at Tenochtitlán.

Cortes stayed in Tlaxcala about three weeks, giving his men time to

recover from their wounds from the battles.

In October, Cortés and his

Tlaxcalan allies than proceeded to the large indigenous city of Cholula, an

Aztec religious stronghold, where for uncertain reasons, the Spanish forces and

Cholulans got into fight that resulted in the “Massacre of Cholula,” where

Cortés’ army killed thousands of people and burned the city.

The massacre had a chilling

effect on other city-states and groups affiliated with the Aztecs. In addition to Tlaxcala, Cortés made additional

alliances with tributary states of the Aztec Empire, as well as political

rivals, including Texcoco and other city-states bordering Lake Texcoco

On November 8, 1519, after months

of battles and negotiations to overcome the diplomatic resistance of the Aztec

Emperor Moctezuma II to his visit, Cortés and his forces entered Tenochtitlán. Cortés was greeted by Moctezuma II, after

which he took up residence in the Aztec capital with fellow Spaniards and

indigenous allies. Believing that the

Spaniards were the return of characters from Aztec legend, and destined to rule

these lands, Moctezuma II pledged his loyalty to the King of Spain and accepted

Cortés as the King’s representative.

In mid-November 1519, Aztecs

killed seven Spanish soldiers that Cortés had left on the coast. After that, Moctezuma II was held as Cortés’

prisoner against any further resistance.

The Emperor was made to pay a tribute to the Spanish King, which

included a treasure of gold objects and jewels.

Moctezuma II continued to act as Emperor, subject to Cortés’ overall

control.

In April 1520, a large second

Spanish force landed on the Gulf Coast, sent by the Governor of Cuba to reign

in Cortés’ conquest efforts that the Governor thought exceeded his

authority. Cortés left Tenochtitlán and

hurried east with forces to combat the newcomer Spaniards. He surprised his antagonists with a night

attack, defeated them, and convinced the defeated Spaniards to join him in his quest,

promising to make them rich.

Cortés returned to Tenochtitlán to

find that the headstrong soldier he had left in charge to guard Moctezuma II,

Pedro de Alvarado, had attacked and killed many of the Aztec nobility during a

religious festival. The population of

the city revolted and fierce fighting ensued.

In early July, the Spaniards and their allies started a retreat across

the causeways to the mainland. The

retreat quickly turned into a rout and much of the wealth that the Spaniards

had acquired in Tenochtitlán was lost. The Spaniards and native allies suffered heavy

casualties. The Emperor Moctezuma II was

killed in the Spanish fighting retreat, along with his son and two daughters,

and several Aztec noblemen loyal to Cortés.

In mid-September, Cuitlahuac,

younger brother of Montezuma II was elected the Aztecs new emperor.

Meanwhile, the Spanish completed

their escape to Tlaxcala, where they were given assistance and the wounded

recovered.

The joint forces of Cortés and

Tlaxcala proved to be formidable. One by

one they took over most of the balance of the cities under Aztec control in

central Mexico, some in battle, others by diplomacy. In the end, only Tenochtitlán and a few small

city states remained unconquered or not allied with the Spaniards.

While Cortés was rebuilding his

forces and garnering more supplies, a smallpox epidemic struck the natives of

the Valley of Mexico, particularly affecting the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán,

where the disease raged from mid-October to mid-December 1520. Between 30-40% of the population died,

drastically weakening the Aztec defense.

The Aztec Emperor, Cuitlahuac, contracted the disease and died after

ruling for only 80 days.

In late December, the

Spanish-Tlaxcalan forces moved to Texcoco, on the eastern edge of Lake Texcoco,

and joined with Texcocan allies. In

Texcoco, Cortes built 13 brigantines (two-masted sailing ships) and mounted

them with canon, planning on turning Lake Texcoco into a strategic body of

water to assault Tenochtitlán. Cortés now

had 84 horsemen, 194 crossbows and muzzle-loaded long guns, plus 650 Spanish

foot soldiers. Additionally, he had

20,000 allied warriors.

Cortés’ siege of Tenochtitlán

began in mid-May 1521, with Pedro de Alvarado playing an important role as

leader of one of the three Spanish assault groups. Spanish forces cut off

Tenochtitlán’s food supply across the causeways and destroyed the aqueducts

carrying water to the city.

At first, battles centered on the

causeways, where the Aztecs continually attacked the Spaniards trying to

advance into the city. In one encounter,

the Aztecs defeated the Spanish forces on a causeway, captured prisoners, and

later ritually sacrificed them atop their Great Temple.

But the stranglehold on

Tenochtitlán tightened and famine began to affect the Aztecs. The Spanish received a large amount of

supplies from Veracruz, and somewhat renewed, in mid-July, they finally entered

the main part of Tenochtitlán. Despite

inflicting heavy casualties, the Aztecs could not halt the Spanish advance.

On August 1, Spanish-Tlaxcalan-Texcocan forces entered the

center of the city, and the last stand for the Aztec defenders began. The Aztec forces were destroyed and the Aztecs

surrendered on August 13, 1521.

The

stubborn Aztec resistance, had been organized by their new emperor, Cuauhtémoc,

the cousin of Moctezuma II, who was captured trying to escape the city in a

canoe.

Cortés

then ordered the idols of the Aztec gods in the temples to be taken down and

replaced with icons of Christianity. He

also announced that the temple would never again be used for human sacrifice.

Human sacrifice had been a major reason motivating Cortés and encouraging his

soldiers to avoid surrender while fighting to the death.

Tenochtitlán

had been almost totally destroyed by Spanish canons, the manpower of the

Tlaxcalans, plus subsequent fires during the siege, and once it

finally fell, the Spanish continued its destruction, as they soon began to

establish the foundations of what would become Mexico City on the

site. The surviving Aztec people were forbidden to live in Tenochtitlán and the

surrounding isles, and were banished.

Up

to 240,000 people were killed in the campaign overall, including warriors and

civilians. Almost all of the Aztec nobility were

dead, and the remaining survivors were mostly young women and very young

children. At least 40,000 Aztecs

civilians were killed or captured.

After

the fall of Tenochtitlán, the remaining Aztec warriors and civilians fled the

city as the Spanish allies, primarily the Tlaxcalans, continued to attack even

after the surrender, slaughtering thousands of the remaining civilians and

looting the city. The Tlaxcalans did not spare women or children: they entered

houses, stealing all precious things they found, raping and then killing women,

stabbing children. The survivors desperately scrambled out of the city

for the next three days.

The

Spanish lost between 450-860 soldiers in the three-month siege of Tenochtitlán,

while 20,000 Tlaxcalans perished.

It

is estimated that around 1,800 Spaniards died from all causes during the more

than two-year campaign - from Veracruz to Tenochtitlán.

Cortés’s victory at Tenochtitlán set in motion the rapid

collapse of the Aztec Empire. The

Spanish already controlled lands of the present-day Mexican states of Mexico,

Quarétaro, Hidalgo, Tlaxcala, Morelos, Puebla, and Veracruz. Over the next three years, the conquistadores

brought the balance of the Aztec Empire, mainly in today’s Mexican states of

Guerrero, Oaxaca, and western Tabasco under Spanish rule and established

the colony of New Spain.

For reference during the discussion of the Spanish Conquest,

I include below a map of the current states of Mexico.

After the fall of Tenochtitlán, there was little resistance

by the people of the Guerrero area to the Spanish, who were interested in

Guerrero’s minerals and coast. During

the Spanish Colonial period, Acapulco became the main western port for New

Spain, connecting this part of the Spanish Empire to Asia.

In the Oaxaca area, the Spanish overcame the main Aztec

military stronghold only four months after the fall of Tenochtitlán. For the most part, the indigenous Zapotecs

and Mixtecs chose not to fight the newcomers, instead negotiating to keep most

of the old hierarchy but with ultimate authority to the Spanish. Resistance to the new order was sporadic and

confined to the Mixtec coastal region; the last major rebellion occurred in

1570.

The complete conquest of Tabasco by the Spaniards was delayed

until the late 16th century due to indigenous uprisings and the

Spanish preoccupation with dominating the central valley of Mexico.

During the Colonial era, Veracruz was the main port of entry

for Spanish military reinforcements, immigrants from Spain, slaves, and

all types of luxury goods for import and export. Because of the decimation of indigenous populations

from European diseases, the Spanish imported between 500,000-1,000,000 West

African slaves between 1535 and 1767. The

route between Veracruz and the Spanish capital of Mexico City, built on the

site of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlán, was the key trade route during the Colonial era. Veracruz became the principal and often only

port to export and import goods between the colony of New Spain and

Spain itself. Until 1778, almost all trade in and out of New Spain had to

be with Spain, except for some limited trade with England and other Spanish

colonies.

Hernán Cortés continued to make

history in Mesoamerica. After fall of

Tenochtitlán, he was appointed by King Charles of Spain as governor, captain

general and chief justice of the newly conquered territory. From 1524-1526, he headed an expedition to

Honduras where he defeated Spaniard Cristóbal de Olid, who had claimed Honduras

as his own, a move Cortés regarded as treason.

Cortés was then suspended from his governorship, over concern for his

increasing reach for power. In 1528,

Cortés sailed to Spain to appeal to the King, and returned to Mexico in 1530

with new titles and honors, but with diminished power. In 1536, Cortés explored

the northwestern part of Mexico, discovered the Baja California Peninsula, and

explored the Pacific Coast of Mexico. He

retired to an estate about 30 miles south of Mexico City, acquired several

silver mines southwest of Mexico City in today’s Mexican state of Guerrero, and

on a second trip back to Spain, died of pleurisy in 1547.

Western Mexico (1522-1531/1590): Michoacan, Chichimecas. To the northwest of the Aztecs, was the

Michoacan region, where the dominant indigenous group was the Tarascan state. The Tarascans were present in the region as

early as 100 BC and developed into a sophisticated culture with a high degree

of political centralization and social stratification by 1350. The Tarascan capital and largest settlement

was at Tzintzúntzan on the northeast arm of Lake

Pátazcuaro. The Tarascans controlled

some 90 plus cities around the Lake. By

1522, the population of the basin was as high as 80,000, while the population

of Tzintzúntzan was about 35,000.

Extensive irrigation and terracing were built to make such a large

population sustainable on local agriculture. The Tarascans built monumental

pyramids and were among the few Mesoamerican civilizations to use metal for

tools, ornamentation, and weapons.

Second only to the Aztec Empire,

the Tarascans controlled an empire of almost 30,000 square miles, occupying the

present-day Mexican state of Michoacan, and parts of Jalisco and Guanajuato. Contemporary

with, and an enemy, of the Aztec Empire, the Tarascans blocked Aztec expansion

to the northwest.

In 1522, a Spanish force was sent

into the Tarascan state, where the Taracans submitted without a fight, and for

their cooperation, were granted a large degree of administrative autonomy. But in 1530, believing that the Tarascans

state were supplying the Spanish with only a small part of the resources

extracted from the population, the Spanish sent to the Tarascan state conquistador

Nuño de Guzmán, today known for brutality against the indigenous peoples and

instituting a system of slave trade, where captured natives would be sent to

the Caribbean. Guzmán, a rival of

Cortés, and a past high ranking colonial administrator, arrived at the Tarascan

State with a large army of Spaniards and indigenous allies. Unsuccessfully

looking for gold, Guzman tortured and then executed the Tarascan ruler,

beginning a period of violence and turbulence.

During the next decades, Tarascan puppet rulers were installed by the

Spanish government.

Guzmán proceeded to launch a

fierce campaign north into the lands of the Chichimeca, a nomadic people who

invaded central Mexico from the north in the 12th and 13th

centuries. Typically, the conquistadors

attacked an Indian village, stole the corn and other food, razed and burned the

dwellings, and tortured the native leaders to gather information on what riches

were in the area. For the most part,

these riches did not exist. Undeterred,

Guzmán continued the violent suppression of the Chichimecas and in 1531, established

the Kingdom of New Galicia, covering the present-day Mexican states of

Aguascalientes, Guanajuato, Colima, Jalisco, Nayarit, and Zacatecas.

Because reports of Guzmán’s’

treatment of the indigenous people had reached Mexico City, Guzmán was arrested

in 1536, held as a prisoner for more than a year, and then sent to Spain. He was released from prison in 1538, and returned

to Mexico in 1539, where he remained on the Spanish payroll as a bodyguard

until his death in 1558.

Guzmán’s violent conquest left

Spanish control of the area unstable, and from 1540-1554 full war reemerged between

Spanish settlers and the native peoples of the area. In 1546, the Spanish discovered silver in the

Zacatecas region and established mining settlements in Chichimeca territory,

which altered the terrain and the Chichimeca traditional way of life. The Chichimeca War (1550-1590) started with

the natives attacking travelers and merchants along the “silver roads.” This war would become the longest and

costliest conflict between Spanish forces and indigenous peoples in the

Americas. Thousands of Spanish died and

mining settlements in Chichimeca territory were continually under threat. With no military end in sight, in 1590, Spanish

authorities launched a full-scale peace offensive by offering the Chichimecas

lands, agricultural supplies, and other goods.

This “peace by purchase” finally brought an end to the war.

Personal Note: The above description of wars between Spanish

settlers and the indigenous people of Chichimeca perhaps doesn’t fit in the

discussion of the Spanish conquest of Mesoamerica, because the region was

“under control” of the Spanish government much earlier, in 1531. But I included it here due to Conquistador

Guzmán’s impact on the region.

Eastern Mexico (Tabasco,

Chiapas, Yucatán), Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, El Salvador (1524-1697): Maya. The Spanish conquest of Mayan

territory was sporadic and difficult to complete because there was no overall

capital city or central political authority to conquer, only widely dispersed

independent groups, with many population centers and villages inaccessible in

dense jungles.

The conquest of the Maya regions

began in 1524, when Hernán Cortés sent Spanish conquistador Pedro de Alvarado into

the highlands of Guatemala and ended 175 years later in 1697 with the final

defeat of the Itza people in the Guatemala lowlands. Over the course of the conquest, there were continual

military incursions into the Maya highlands, lowlands, and Yucatán; many battles;

and often rebellions and put-downs after initial conquests. The Spanish exploited fragmentation of the

Maya by taking advantage of pre-existing rivalries between various groups and

making strategic alliances, as they did in conquering the Aztecs. Many peoples were relocated to suit the aims

of the conquerors. The Spanish persisted

in the eradication of Mayan culture, stealing or destroying their ceremonial

objects and burning their writings.

Disease and forced labor also took a horrible toll on the indigenous

populations.

Legacy of the Spanish Conquest

The initial shock of the Spanish Conquest was followed by

decades of heavy exploitation of the indigenous peoples, allies and foes alike.

During the Conquest, Spaniards legally

enslaved large numbers of natives - men, women, and children - as booty of warfare,

branding each individual on the cheek.

Native slavery was abolished in 1542, but persisted into the 1550s. Due to some horrifying instances of abuse

against the native peoples, Spanish religious leaders suggested importing black

slaves to replace them, but saw even worse treatment given to black slaves.

Over the years, Colonial rule gradually imposed Spanish

cultural standards on the subjugated peoples. The Spanish created new

settlements laid out in a grid pattern in the Spanish style, with a central

plaza, a church and the town hall housing the civil government. This style of

settlement can still be seen in the villages and towns.

The introduction of Catholicism was the main

vehicle for cultural change, and resulted in a blend of Catholicism and native

religious customs. Catholic missionaries

campaigned against cultural traditions of the natives; Old World cultural

elements came to be thoroughly adopted by indigenous groups. The Aztec education system was completely

abolished and replaced by a very-limited church education.

Immediately after the Conquest in central Mexico, the Spanish

continued the Aztec system of ruling elites, and tribute-paying commoners. The

indigenous nobility were largely recognized as nobles, with privileges,

including the noble Spanish title Don for noblemen and Doña for

noblewomen.

The greatest change was replacement of the ancient

Mesoamerican economic order by European technology and livestock; this included

the introduction of iron and steel tools to replace late stone age tools,

and of cattle, pigs and chickens. New crops

were also introduced; however, sugarcane and coffee led to plantations that

economically exploited native labor. During the second half of the 18th

century, adult male full-blooded natives were heavily taxed, often being forced

into debt peonage.

In the 16th century, perhaps 240,000 Spaniards entered the

conquered Mesoamerican regions. They

were joined by 450,000 in the next century. Unlike the English-speaking colonists of North

America, the majority of the Spanish colonists were single men who married or

made concubines of the natives. As a

result of these unions, mixed race individuals known

as mestizos became the majority of the Mesoamerican population in the

centuries following the Spanish Conquest.

Mesoamerica

was not the only region of Spanish conquest in the Americas. The overseas

expansion was initiated under Spanish royal authority to secure riches, expand trade,

and spread the Catholic faith

through indigenous conversions.

The Americas were to be invaded and incorporated into the Spanish Empire.

Beginning

with the 1492 arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Caribbean, and

continuing over three centuries, the Spanish Empire would expand

across the Caribbean Islands, half of South America, most of

Central America, and much of North America, including present-day Mexico,

Florida, and the Southwestern and Pacific Coastal regions of the United States.

Comments

Post a Comment