HISTORY4 - Mount Rushmore Rocks!

Pat and I are signed up for a tour in September that includes

Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks and Mount Rushmore National Memorial. I’ve never been to Mount Rushmore before, so

ahead of the trip, I wanted to know more about Mount Rushmore’s history - hence

this article as a “learning tool.” I

will write about the tour - complete with our best photos - after the trip.

Mount Rushmore is a U.S. National

Memorial located in the Black Hills of South Dakota. It features spectacular 60-foot sculptures of

the heads of four prominent U.S presidents:

George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore

Roosevelt. Construction began in 1927

and lasted until 1941. Sculptor Gutzon

Borglum designed and oversaw the project.

|

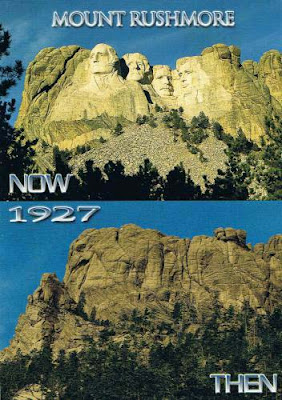

| Before and after views of the Mount Rushmore carvings. |

The Idea

In 1923 South Dakota State

Historian Doane Robinson suggested carving the likenesses of famous people into

the Black Hills region of South Dakota for the purpose of promoting

tourism. Robinson wanted the sculpture

to feature heroes of the American West, like Lewis and Clark, Red Cloud, and

Buffalo Bill Cody. His initial idea was to sculpt the “Needles,” a formation of

granite pillars, near Custer South Dakota.

Sculptor Gutzon

Borglum

In 1924 Doane Robinson contacted

sculptor Gutzon Borglum, who was then managing the carving of a Confederate

Memorial on Stone Mountain in Georgia.

Robinson was looking for the man to fulfill his dream in the Black Hills

of South Dakota.

The son of Danish immigrants, Gutzon Borglum was born in 1867 in what

was then the Idaho Territory. By 1901 he

was sculpting portraits and group figures; his reputation increased rapidly. He continued sculpting memorials and public

works until 1923 when he began work on the Confederate Memorial on Stone

Mountain in Georgia - an immense high relief sculpture depicting Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and Jefferson Davis. Borglum was increasingly at odds with local

officials at Stone Mountain over management and financial issues, so when Doane

Robinson approached him about the Black Hills job, Borglum was ready to listen. In 1925 Borglum left Georgia permanently,

relinquishing the Confederate Memorial to a successor, but having developed the

necessary techniques for carving huge sculptures that made Mount Rushmore

possible.

Gutzon Borglum had a fascination with gigantic scale and themes of

heroic nationalism that suited his extroverted personality. He was domineering, a perfectionist, and had

an authoritarian manner that brought tensions to large projects.

Robinson decided that Borglum was

the sculptor for the job and discussions began with local officials to confirm

the appropriate site in the Black Hills, the theme of the sculpture, and the

persons to be honored. Borglum

immediately imposed his strong opinions.

He rejected the “needles” site because of the poor quality of the

granite and strong opposition from Native American groups. They settled instead on a site a few miles

northeast of the Needles, near Keystone, South Dakota, atop 5,725-foot Mount

Rushmore, named in 1885 after Charles E. Rushmore, a prominent New York

lawyer. Mount Rushmore had the advantage

of stronger granite and faced southeast for maximum sun exposure on the

completed sculpture.

|

| The Black Hills area of South Dakota. |

Borglum strongly pushed the idea

that the sculpture should have broader historic appeal, commemorating America’s

founders and builders, and convinced the South Dakota decision makers that they

should honor four U.S. presidents for what they represent to the country: Washington for the birth of the nation,

Jefferson for growth, Roosevelt for development, and Lincoln for preservation

of the union.

Initial Approval and

Funding

South Dakota Senator Peter

Norbeck and Congressman William Williamson were instrumental in getting

legislation passed to allow the carving of the memorial on “federal land.” The U.S. Congress and the South Dakota

Legislature passed the necessary bills in March 1925. On October 1, 1925 Borglum organized an

informal dedication of Mount Rushmore as a national memorial.

The Mount Rushmore site was sacred Indian land. An 1868 treaty with the U.S. government guaranteed

that the Lakota tribe could keep the Black Hills forever. But once gold was found and confirmed in 1874

(by Lt. Col. George Custer), the U.S. government and prospectors grabbed the

land back and drove the Lakota away.

Money for the project was harder

to find. Borglum lobbied heavily in

Washington DC for the Mount Rushmore carving and by early 1927 achieved

success. On August 10, 1927 President

Calvin Coolidge attended the formal dedication ceremony for the Mount Rushmore Memorial

and promised federal funding for the project.

Coolidge soon signed a bill authorizing government funds to get started

and creating a 12-member Mount Rushmore National Memorial Commission. Gutzon Borglum now had approval, funding, and

a contract to begin the carving of Mount Rushmore.

|

| President Calvin Coolidge delivers a speech on August 10, 1927 at the formal Mount Rushmore Memorial dedication ceremony. |

Construction

The carving of Mount Rushmore

began in October 1927 and proceeded intermittently until October 31, 1941,

interrupted periodically by scope, funding, and weather issues. The presidential faces were completed one at

a time, left to right. Over the 14-year

effort, about 400 people worked on the project - usually around 30 per year. The

workforce included former local miners as drillers and carvers, plus support

people like errand boys, blacksmiths, carpenters, and housekeepers. Around 450,000 tons of rock was removed from

the face of the mountain. Washington was

completed and dedicated in 1934, Jefferson in 1936, with President Franklin Roosevelt

attending the dedication that year, and Lincoln in 1937. The face of Theodore Roosevelt was finally

completed in 1939. Gutzon Borglum died

in March 1941 from complications during surgery; work continued under the

direction of his son, Lincoln Borglum, until final drilling in October

1941. No deaths occurred during the 14

years of the project. The Mount Rushmore

carving project came to an end when funding ceased due to World War II

requirements. According to the National

Park Service, the entire project cost just under a million dollars, a real

bargain by todays’ standards, 84% paid by the federal government.

Borglum started with a 1/12th

scale model (one inch on the model translated to one foot on the mountain) and

invented an ingenious method to transfer his design from the model to the face

of the mountain.

A Black Hills, Badlands &

Mount Rushmore pamphlet describes the “pointing” process:

“To transfer measurements from

the model to the mountain, workers determined where the top of the [mountain]

head would be, than found the corresponding point on the model. A protractor was mounted horizontally on top

of the model’s head. A similar, albeit

12-times larger apparatus was placed on the mountain. By [carefully measuring angles and distances

to various points on the model and] substituting feet for inches, workers

quickly determined the amount of rock to remove.”

|

| Gutzon Borglum's final model of the Mount Rushmore Memorial. Note the man at right center of the 1/12th-scale model. |

Rex Allen Smith, in his book, The Carving of Mount Rushmore, describes

how the carving was accomplished. The

carvers were lowered down the 500-foot face of the mountain in bosun chairs

held by 3/8-inch thick steel cables.

“… the rough shaping was done by

the drillers [using dynamite], who worked down to within about six inches of

the finished surface of the heads, and in the process they removed granite by

the foot and by the ton. [About 90% of

the granite was removed with dynamite.] Then

the carvers took over. By ‘honeycombing’

- drilling grids of very shallow and closely spaced holes and breaking out the

material between - they worked down to very near the finished ‘skin,’ and in

doing so they removed stone by the inch and the pound.

Then came the finishing. This was done by carvers using “bumpers” -

light, handheld pneumatic hammers … against the granite and removed it by the

fraction of an inch and by the ounce. … Then, closely supervised by Gutzon or

Lincoln, they shaped on the stone faces those subtle nuances … that give living

faces age and character and personality.”

Italian immigrant Luigi Del

Blanco, who had worked for Gutzon Borglum on Stone Mountain, was hired as Chief

Carver because of his incredible ability to show emotion and personality in

stone. Between 1933 and 1940, he carved

the refinement of expressions on the four faces.

|

| Work proceeds on the Washington and Jefferson sculptures. |

|

| Finishing work around the nose of the Lincoln figure. |

|

| Gutzon Borglum inspects the carving on Mount Rushmore. |

A couple of unplanned oddities occurred during

construction. Thomas Jefferson was

originally supposed to be on the right side of George Washington. They started sculpting Jefferson in that

position but after almost two years of work, ran into complications with the

granite, had to dynamite their first attempt off the mountain, and “squish” him

in on Washington’s left side. Also, in

1937 a bill was introduced to Congress that pushed for Susan B. Anthony, of

women’s suffrage fame, to be added to the sculpture as a fifth personage. That idea was quashed quickly, with the funding

restricted to the four presidents.

Limited funding had already

caused changes to the original plan. The

presidents were supposed to be carved from the waist up, but insufficient

funding reduced the scope of the effort.

Beyond the sculpture of the presidents, Gutzon Borglum had grander plans

for the design of the monument. He

wanted to add a map of the Louisiana Purchase on the face of the mountain and,

within the map, carve some of the nation’s highest accomplishments and

significant events. Insufficient funds

curtailed this idea too.

Funding and management issues

challenged the construction of the Mount Rushmore Memorial over the entire

period of construction. John Boland,

former mayor of Rapid City South Dakota, and the first president of the

executive committee of the Mount Rushmore National Memorial Commission, was

responsible for the project’s finances in the early years of construction. Boland and Borglum were at odds constantly

over everything from schedules, to timely release of funds, paying bills, and

even publicity, but Boland’s efforts ensured adequate funding, even during the

depths of the Great Depression. During

the 1930s Senator Norbeck worked tirelessly to secure continued funding through

emergency relief programs that were part of President Roosevelt’s New Deal.

In 1933 an executive order by

President Roosevelt placed Mount Rushmore under the jurisdiction of the

National Park Service (NPS). Gutzon

Borglum, always uneasy with outside control over his projects, resented being

under “the watchful eye” of the government.

In 1938 the U.S. government

authorized Gutzon Borglum’s “special addition.”

Between 1938 and 1939, a 70-foot tunnel was dug in a canyon behind the faces

carved on the Mount Rushmore’s thin mountain ridge. The tunnel was to be the entrance to “The

Hall of Records at Mount Rushmore,” intended to hold important U.S. documents

such as the Constitution and Declaration of Independence. These plans seemed to die with Gutzon in 1941

and the onset of World War II, but on August 8, 1998 the tunnel was

commemorated into a small Hall of Records, containing the story of Mount

Rushmore’s creation, a brief history of the United States, and engravings of

the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. Today, the entrance to the hall is sealed

behind a 1,200-pound granite slab, for far-future generations to discover.

|

| At center right, behind the head of Lincoln, you can see the entrance to the Hall of Records tunnel. |

|

| The completed Mount Rushmore Memorial. |

Preservation

The ongoing conservation of the

Mount Rushmore Memorial site is overseen by the U.S National Park Service

(NPS). In 1989 the NPS and the Mount

Rushmore Society began studies to understand the structural integrity of the

monument and where the weak points might arise over the years. The major blocks of granite and fractures that

make up the mountain were identified and mapped in three dimensions. In 1998 electronic monitoring devices (along

with 8,000 feet of camouflaged copper wire) were installed to track movement of

the rock structure to an accuracy of three millimeters (one ninth of an inch). Since 2009, movements at the site have been

digitally recorded using a laser scanning methodology. The copper wire was replaced with fiber optic

cable.

The 1989 study also helped to

test the original sealant for cracks, applied by Gutzon Borglum. The sealant devised by Borglum, a mixture of

linseed oil, white lead, and granite dust, was found to have dried out quickly

and became ineffective at keeping water out of the cracks.

NPS staff began removing the old

sealant and replacing it with a modern silicone sealant, that is better able to

withstand the extreme temperature and moisture variations that occur on Mount

Rushmore. Similar to what Borglum had

done, the silicone is camouflaged after it is applied by sprinkling granite

dust on its surface.

According to geologists, the granite, from

which the memorial is carved, erodes only one inch every 10,000 years, so the

monument will be around a long, long time.

National Memorial

On October 15, 1966 Mount

Rushmore was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In 1991 President George H. W.

Bush attended the 50th anniversary of completing the Mount Rushmore

Memorial.

Visitor facilities have been

added over the years, including a visitor center, the Lincoln Borglum Museum,

and a Presidential Trail. You can also visit the Sculptor’s Studio, where Gutzon

Borglum worked on his scale models.

Mount Rushmore has become an

iconic symbol of the U.S. and today is South Dakota’s top tourist attraction,

with about 2.5 million visitors annually.

Comments

Post a Comment