HISTORY3 - Southeastern Arizona's Wild West

In my first group of history articles on this blog, I want to provide a

flavor of my recent writing that I collected and self-published in three

electronic books available for reading on my website, ringbrothershistory.com, under “Bob’s Projects.” This article is adapted from Southeastern

Arizona Reflections - Living History from the Wild West.

Over a period of a little more

than 25 years, from the late 1870s to the early 1900s, southeastern Arizona

earned its legendary reputation of being the “Wild West.” The time was characterized by fierce Apache

resistance, increased ranching operations, rapidly growing mining boom towns,

smuggling and cattle rustling across the U.S.-Mexico border, and a blooming

network of stagecoach lines and railroads.

Besides Apache raids across

southeastern Arizona until 1886, Cochise County, and particularly Tombstone,

was where most of southeastern Arizona’s Wild West action was. There was considerable tension between the

rural residents who were for the most part Democrats from the agrarian

Confederate States, and town residents and business owners who were largely

Republicans from the industrial Union States.

During the rapid growth of Cochise County in the 1880s, at the peak of

the silver mining boom, outlaws frequently robbed stagecoaches and brazenly

stole cattle in broad daylight. Between

1877 and 1882, bandits robbed 36 stagecoaches in southeastern Arizona.

In 1876, teenager Henry McCarty,

who would later be known as William H. Bonney and then Billy the Kid, fled to

territorial Arizona from New Mexico after stealing clothing and firearms, and

was hired as a ranch hand by Henry Hooker at the Sierra Bonita Ranch, north of Willcox. After murdering a blacksmith during an

altercation in 1877, McCarty returned to New Mexico, participated in the

Lincoln County War, and was eventually shot and killed by Sheriff Pat Garrett

in 1881.

Cattle rustlers from both the

U.S. and Mexico used the International border to raid across in one direction

and find sanctuary on the other side.

Bandits were even stealing horses from the Santa Cruz River Valley and

selling the livestock in Sonora, Mexico.

Mexican authorities complained about American outlaw Cowboys who stole

Mexican beef and resold it in Arizona.

The Clanton and McLaury clans were among those allegedly in the

cross-border livestock smuggling from Sonora into Arizona.

Note: A cowboy in that time and

that part of the country was generally regarded as an outlaw. Legitimate cowmen were referred to as cattle

herders or ranchers.

Between 1878 and 1881, there were

a number of deadly engagements along the border (including the First and Second

Skeleton Canyon Massacres, and the Guadalupe Massacre in the Peloncillo

Mountains) involving American Cowboys, Mexicans, or the Mexican militia - each

trying to get the upper hand in local smuggling and cattle rustling operations.

Shootings were commonplace,

especially in and around Tombstone. The

townspeople and business owners welcomed the Cowboys who spent money in the

numerous bordellos, gambling halls, and drinking establishments. As officers of the law, the five Earp

brothers (Wyatt, Virgil, Morgan, James, and Warren) held authority at times on

the federal, county, and local level.

They were resented by the Cowboys for their rough tactics, including

buffaloing drunken troublemakers. And

the lines between the outlaw element and law enforcement were not always

distinct.

Here are a few examples of the

Wild West mayhem that occurred over a three-and-a-half year period, during

Tombstone’s peak mining years:

In mid-June 1880, a drunken,

estranged husband shot at his rival on the porch of Tombstone’s Cosmopolitan

Hotel, but missed, and was in turn shot and killed by his rival.

On October 28, 1880, Tombstone

town marshal Fred White was trying to break up a group of late night revelers

shooting at the moon on Allen Street. He

attempted to confiscate the pistol of Cowboy Curly Bill Brocius and was shot

(supposedly accidentally) in the abdomen and later died.

On January 14, 1881, Tombstone

gambler Michael O’Rourke got into a disagreement with the chief engineer of the

Tombstone Mining and Milling Company and shot and killed him.

On February 28, 1881, Tombstone

professional gambler and gunfighter Charlie Storm was killed by Luke Short in

self-defense after being confronted by Storm for the second time that month.

On October 1, 1881, in nearby Charleston,

drunken James Hickey taunted and harassed gun fighter Billy Claiborne until

Claiborne shot and killed him.

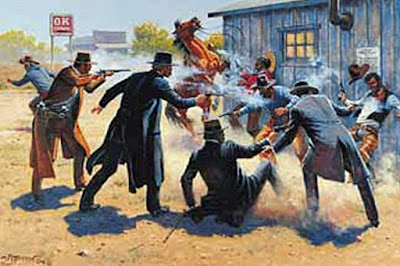

The most famous shooting occurred

in Tombstone on October 26, 1881 when a group of lawmen led by Marshall Virgil

Earp and two brothers Wyatt and Morgan, plus the infamous John “Doc” Holiday,

tried to arrest five Cowboys for violating a city ordinance against carrying

weapons in town - in a confrontation that became known as the “Gunfight at the

OK Corral.” The lawmen prevailed, but

the Cowboys would seek revenge.

On December 28, 1881, Virgil Earp was shot-gunned and maimed while walking the streets of Tombstone.

On March 18, 1882, Morgan Earp

was shot through a window and killed while playing billiards in Tombstone.

On March 20, 1882 Cowboy Frank

Stillwell was killed by Wyatt Earp in Tucson, on Earp’s so-called Vendetta Ride

in retaliation for the shooting of Virgil and Morgan Earp.

On March 24, 1882, Curly Bill

Brocius was killed by Wyatt Earp in the Whetstone Mountains, about 20 miles

from Tombstone, also on Earp’s so-called Vendetta Ride.

On July 13, 1882, Cowboy and

gunman Johnny Ringo was shot near Chicauhua Peak. His death was ruled a suicide, but alternate

theories suggest Ringo was killed by Wyatt Earp, Doc Holiday, or others.

On November 14, 1882, Frank

Leslie became involved in an argument in Tombstone with Billy Claiborne who

shot at Leslie but missed, and was killed by Leslie who returned fire.

On February 23, 1883, in

Tombstone May Woodman shot and killed William Kinsman, who although living with

her at the time, had published his intentions not to marry her in the Tombstone

Epitaph newspaper.

On December 8, 1883, six outlaw

Cowboys robbed a Bisbee mercantile store, killing four people, later referred

to as the Bisbee Massacre. Six men were

arrested and convicted, and five of them were hanged on March 28, 1884 - the

first criminals to be legally hanged in Tombstone, then the county seat. The sixth outlaw was sentenced to life

imprisonment.

|

| Grave marker in Tombstone's Boot Hill Cemetery for the five outlaws who were hanged for committing the Bisbee Massacre. (Courtesy of Wikimedia) |

With the onset of Tombstone’s mining difficulties in the mid 1880s, the pace of gunfights and outlawry slackened also.

But in 1886, Cochise County

Sheriff John Slaughter was chasing the Jack Taylor gang, wanted for robbery and

murder, who were visiting relatives in Tombstone. In the ensuing gunfight, at Contention City,

near Tombstone, two of the gang members were shot and killed. Two others escaped but were later killed in

Mexico.

As late as the early 1900s, there

were active outlaw gangs in southeastern Arizona. Former lawman Burt Alvord

resigned his post as a sheriff’s deputy in 1899 and together with partner Billy

Stiles, began a series of armed robberies, including train robberies. They were captured, escaped, and wounded, but

persisted until they were captured for the final time in Mexico in 1904.

Some towns became refuges for

outlaws of the day. One such town,

Galeyville, on the eastern edge of the Chiricahua Mountains, was a silver

mining site for a short period, before it busted, and became the home of a pack

of outlaws led by Curly Bill Brocius, who for a time was known as the outlaw

king of Cochise County. The mining town

of Pearce was, for a period, the home of the Alvord-Stiles gang.

With the rapid decline of

Tombstone in the late 1880s and the final surrender of Apache leader Geronimo

in 1886, the so-called Wild West started to wind down, and by the early 1900s,

had ceased to exist.

Comments

Post a Comment